|

| Ashley Rhodes-Courter. Image: Eckerd College |

Ashley Rhodes-Courter once lived in a 2 bedroom trailer with 16 other children, all of whom, Ashley included, were beaten and starved on a regular basis.

She later lived with a convicted pedophile.

For a while she lived with her alcoholic biological grandfather, during which time she witnessed him shot to death by a neighbor following an argument.

In a grotesque show of irony, these were the people the state of Florida had selected to pay to protect and house her.

In the 9 years after Ashley was taken away from her biological mother at the age of 3, she lived in 14 foster homes and attended 9 different schools. All of the homes were overcrowded and many were abusive and dangerous – at least 25 percent of her foster parents had some type of criminal record. These were homes unfit for anyone, let alone a child.

Hope for adoption faded more and more with each year that passed. Upon reaching the age of 9, a point at which most children in the foster care system are privately considered “hard-to-place,” or “special needs,” if not “unadoptable,” Ashley saw no hope for finding a family.

So she found her solace in school. She quickly learned that good grades equated to pleased teachers who would likewise give her the praise and encouragement that she so desperately longed for at home. At school Ashley was considered an incredibly dedicated, bright, articulate student, who likewise, constantly garnered praise. Home… was an entirely different story.

Time and again Ashley found herself living in poverty-like conditions, her body bruised, often fearing for her life, and always lacking a real sense of family. But social services surely wasn’t taking action against it; to the contrary, she and her various foster siblings were called liars and manipulators when they tried to shed light on their own plight.

And then, at the age of 12, the unexpected happened. Or as Ashley’s award-winning essay describes it: “three little words.”

The words: “I guess so.”

The question: “Would you like to make this adoption permanent?”

And so it happened: after nearly a decade of emotional torture, neglect, abuse, and suffering, Ashley was given a second chance at normalcy by a couple of Florida “empty nesters,” Gay and Phil Courter, a best-selling novelist and a documentary screenplay writer, respectively.

They were working on a film addressing the different techniques used to find children permanent homes in the U.S. Ashley auditioned and was cast, sharing her story publicly for the first time.

Ashley went from living in a small, overcrowded trailer, to sharing a spacious waterfront home with only her adoptive parents.

|

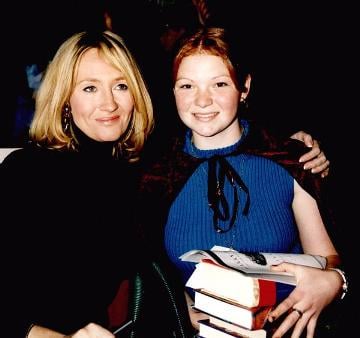

| Ashley with Harry Potter author JK Rowling. Teen girl harnesses magic of Potter |

In many ways, it’s a Cinderella story. But her ‘happily ever after’ is clouded by the knowledge that there are so many children still suffering through the inadequacies of a flawed foster care system.

Another thought pervades her mind: her birth mother and what happened that day in 1989. Her biological mother was only 17 years old when she gave birth to her in North Carolina. Not long after, she became involved with a drug-using boyfriend, and soon she too became a dope addict. To escape the authorities, they fled to Florida with Ashley and her younger half-brother. They were caught, though, and both children were placed in foster care, where they would allegedly be 'safe'. Based on Ashley's experience--and that of her half-brother who was nearly murdered in one of their foster homes and Ashley says is "permanently damaged"--it's anyone's guess as to whether they would have been better off with their biological parents all along.

It frustrates Ashley that they were never given the chance to find out. She says that she doesn’t understand why a state would rather pay complete strangers to care for children, than to help biological parents resolve their problems and retain custody. In her mother’s case, at only 20 years old, all she may have needed was help breaking her addiction, and assistance in getting back on her feet.

Ashley knows she is scarred. Although she loves her doting and attentive adoptive parents and carries their last name, she still refers to them by their first names and says she has a difficult time with deep commitment in relationships in general.

|

| Ashley with President Clinton |

Fortunately, she is able to shine in public and in business and is a sought-after public speaker, using her platform as an advocate for child and adoption rights. She works fervently to bring attention to the plight of the hundreds of thousands of children currently in the U.S. foster care system. She has been featured on national and local television shows, and gives speeches, including 15 keynotes, to groups nationwide, particularly those focusing on child advocacy and adoption. She has spoken to U.S. Senators and Congressmen, and met former President Clinton. She has been on an adoption camp's professional staff for several years, and spent her 2006 summer break working with a children's literacy program in South Africa.

Now 21 years old and a junior at Eckerd college in Florida with double majors in communications and theater, double minors in psychology and political science, and a dean's list-worthy 3.84 GPA, she knows quite well that she is an exception as far as former foster-care children are concerned. Of those who never find permanent homes, fifty percent or less graduate from high school, and less than 2 percent receive a Bachelor's degree. A key point of frustration for Ashley is that adoption trainers often tell prospective families (as they did with Ashley's own adoptive parents) that these older-adoptees are not college-material, and will not work for parents with high expectations. Ashley wants the public to know that it's not that these children lack potential – it's that they have lost hope.

Ashley wants to restore hope in those children. By telling her story, she hopes that children who may feel trapped in an often unjust, lonely, neglectful system will see that there is the potential for a better future. She encourages them to focus on school and other positive activities despite what they may be experiencing at "home." Despite her own experiences, she encourages children to speak up, to find a trusted adult to confide in when they need help.

She also hopes to encourage Americans to consider permanent adoption. It is particularly poignant that she, already in junior high by the time she was adopted, was able to accomplish as much as she has despite nearly a decade of pain and instability. In telling her story, she hopes to shed some of the stigma associated with children often considered "too old to adopt."

Through her activism, she has also helped the Dave Thomas Foundation for Adoption generate 1 million dollars so far.

In 2003, Ashley's essay about her adoption day was selected from 3000 high school students' entries to be published in The New York Times Magazine. In early 2008 it will be published as an expanded memoir titled, Three Little Words. There are also negotiations in the works for a feature film.

In 2004 Ashley and her family were named "Angels in Adoption" by the Congressional Coalition on Adoption Institute. Later that year she won the Child Welfare League of America Kids to Kids National Service Grand Prize, and on top of it all, she was named the 2004 Youth Advocate of the Year for the North American Council on Adoptable Children. She has also received various local and national college scholarships,

She was selected as one of 20 undergraduate students to be named to USA TODAY's 2007 All-USA College Academic First Team, one of only two students from a Florida college or university.

Most recently, Ashley was chosen a recipient of the 2007 Brick Awards prestigious "Golden Brick," through the Do Something organization for social change. The Brick Awards honor young people making a difference in the world. Ashley, who clearly lives up to this, plans to donate the $25,000 first prize to the North American Council on Adoptable Children.

Although Ashley's life is much different today than it was growing up, she feels it is important to embrace where she came from, what she went through, and what she overcame. Although she will continue in her child advocacy work, she also realizes that there is more to her than what she has dubbed "Little Orphan Ashley." She wants to be a scholar, and one day, a mother. And having found her own, she wants to help other children find their dreams again too.

Page created on 7/29/2014 2:44:24 PM

Last edited 3/30/2017 10:18:01 PM