|

| Hugh Herr wearing the PowerFoot. (Sherwin G. Henry for Forbes) |

Hugh Herr is an associate professor in MIT’s Program in Media Arts and Sciences and in the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology. He currently directs the Biomechatronics group at The MIT Media Lab, where his program “seeks to advance technologies that promise to accelerate the merging of body and machine.”

Herr made TIME magazine’s Top Ten Inventions list in 2004 and 2007, he was the winner of the prestigious Heinz Award in 2007 and was 2008’s recipient of the Action Maverick and Spirit of Da Vinci Awards. As a holder or co-holder of at least ten patents, mostly relating to prosthetics, Professor Herr’s inventions are impacting the lives of the disabled everywhere.

|

| Hans Herr |

Hugh Herr is a direct descendant of Hans Herr, an elderly Mennonite bishop who led the first group of European settlers to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. The group built the Mennonite community where Hugh was born. It was here that Hugh and his four older siblings were raised in a tradition of nonviolence. “The Pacifist tradition is something I take very seriously,” Herr was quoted as saying in Boston Magazine, “Mennonites believe in good works. It’s not enough to simply believe. One has to act. One has to make it better for oneself and others.”

This was something Hugh’s father instilled in all his children along with a powerful work ethic. “Do it well and do it with passion” was one of his favorite sayings. ““He would say that if you’re a ditch digger, that’s fantastic," Herr remembers, "Just make the ditch beautiful.”

|

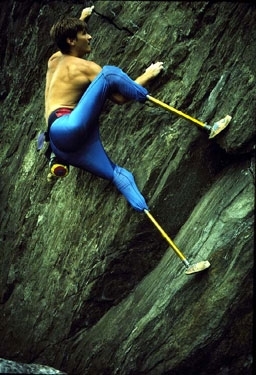

| Hugh Herr climbing (newscientist.com) |

My hero, Hugh Herr, has spent the better part of his life putting those words into action; doing it well and doing it with passion, so much so that Herr has never seemed satisfied with anything but making it all the way to the top. This hunger for excellence first became apparent when he took up climbing. From a very young age, it became clear that young Hugh would be a world-class rock-climber. Born in 1964, Herr wasn’t yet eight years old when he’d scaled Mount Temple, an 11,624 foot peak in the Canadian Rockies. As a teenager, he began climbing without a rope, sending ripples of concern through the climbing community but also awe as the youngster took on tougher and tougher challenges.

It was the winter of 1982 when the young phenom and a climbing partner, Jeff Batzer, attempted to summit New Hampshire’s notoriously temperamental Mount Washington. 1000 feet from the summit, the wind suddenly whipped up to over 100 miles per hour, dropping the temperature to 110 below. The two gave up on the summit and turned back, only to head deeper into the blizzard. After three days in sub-zero temperatures and a failed river-crossing that left Hugh soaked to the waist, the two had all but given up. Meanwhile, a rescue party had already suffered one casualty when Albert Dow, a 28 year-old volunteer was killed in an avalanche. The would-be rescuers would later find that they were looking in the wrong place. Hugh and Jeff had managed to hike nearly five hours from the nearest base station. If not for a local snow-shoer stumbling across their tracks, the two would not have survived. They were airlifted to a hospital in nearby Littleton.

Both climbers would require amputations to limbs affected by severe frostbite. Jeff lost his left lower leg and all the toes on his right foot as well as the fingers on his right hand. It was just over two weeks after their rescue that vascular surgeons gave up on Hugh’s severely frost-bitten legs. Hugh would have both legs amputated just below the knee. For upper-echelon rock-climbers, their losses were devastating, life-changing. Hugh’s climbing partner would quit climbing and join the clergy, but Hugh’s response would take him in a different direction. After being fit with a pair of acrylic legs several months after the surgery, Herr ventured out to rock cliffs near his boyhood home in Lancaster with his new legs… and some tools; tools he would use to shape and carve his prosthetic legs to make them more useful for climbing. It was then that Hugh Herr began his quest for prosthetic legs that not just mimicked real legs, but outperformed them.

Herr began designing, building and testing his own prosthetic legs. Though it meant pain and numerous falls while rock-climbing, Herr’s dream of climbing again was realized in custom-made limbs he designed with sharp edges and spikes to respond to the challenging toe-holds of rock and ice faces. He soon accomplished what no athlete had done before – to compete at an elite level after being fit with prosthetic limbs.

|

| Hugh Miller Herr (Wikipedia Commons) |

Herr was only just beginning. He was determined that the pursuit of superior prosthetic limbs was something he was going to do well, and with passion. At the age of 21, he enrolled at Millersville University where he began working with a Pennsylvania prosthetist named Barry Gosthnian to improve the prosthetic socket: where the leg meets the prosthesis. Their work resulted in the first of many patents for Herr. During his pursuit of a masters in mechanical engineering at MIT and a Ph.D. in biophysics at Harvard with more postdoc work at MIT in biomedical devices, Herr worked on knee and ankle joints and leg braces, constantly improving the strength, weight and functionality of the joints to mimic their human counterparts.

Hugh Herr continues to shatter old beliefs about prosthetics and the disabled. With a grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Herr helped design and test a prosthetic foot whose movements are computer guided. His “PowerFoot” is the first robotic foot to give its wearer a natural gait, as well as the ability to ascend and descend hills and navigate stairways. “PowerFoot” was named one of Time Magazine’s best inventions of the year in 2007 and is a water-mark in Herr’s career: he’s devised a prosthetic that is arguably superior to the body part it replaces.

His growing list of contributions that ease the lives of the disabled certainly makes Hugh Herr an admirable thinker. What makes him MY HERO, however isn’t so much his God-given ability to conceptualize these amazing devices. It’s the way he’s responded to a setback that would leave many defeated. Another hero of mine, legendary football coach Vince Lombardi once said, “It’s not whether you get knocked down, it’s whether you get up.”

In 1982, from the very pinnacle of elite rock-climbing, Hugh Herr got knocked down. In a way that makes things better for others, my hero not only got up, he rose above.

Page created on 3/24/2011 9:47:22 AM

Last edited 3/24/2011 9:47:22 AM

Herr, Hugh. "Biomechatronics Group – Massachusetts Institute of Technology ." [Online] Available http://biomech.media.mit.edu/people/herr.htm.

Adelson, Eric. "Boston Magazine." [Online] Available http://www.bostonmagazine.com/articles/best_foot_forward_february/page2.