Four years after graduating from the University of California at Berkeley with a degree in French Cultural Studies, Alice Waters found herself walking through a grand old Central Market.

It was 1963, it was Paris, and as she wandered through the enormous fruit and vegetable market, Waters was struck by the array of brilliant colors, the music of farmers hawking their produce, and the fact that there, in the middle of a great city, she felt "directly connected to the land."

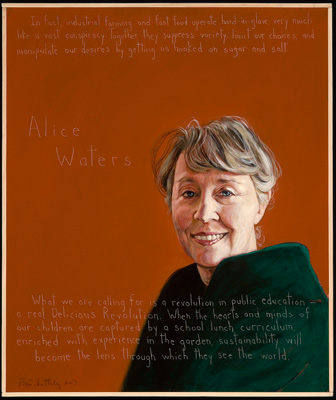

Robert Shetterly

Robert Shetterly

"I had an epiphany," she says. This epiphany resulted in Chez Panisse, a Berkeley restaurant founded upon Waters' ecological philosophy and which, nearly thirty years after opening its doors, has been named "The Best Restaurant in America" by both the James Beard Foundation and by Gourmet Magazine.

To supply the restaurant, Waters bought only food grown in accordance with the principles of sustainable agriculture. Since it opened in 1971, the fixed-price menus offered nightly at Chez Panisse have consisted only of fresh ingredients, harvested in season, and purchased from local farmers.

By pursuing one goal, Waters has accomplished another: she has successfully established relationships with local farmers and become an integral part of the agricultural community (she serves on the board of one of the farmers' markets). In this way she has demonstrated how a restaurant can thrive while contributing to the general welfare of a community.

Waters had always loved cooking for friends, and one of the things she wanted to achieve at Chez Panisse was to reaffirm the bond that people establish with one another by sharing a meal. She values knowing her customers and watching them get to know one another. Waters' philosophy of cooking and eating enables people to connect with the source of their food, both the land it came from and the seasonal cycles in which it was grown and harvested.

In 1996, inspired by The Garden Project at the San Francisco County Jail, Waters decided to apply her principles to education. The Edible Schoolyard Project became Waters' new passion. The project began at the Martin Luther King Middle School in Berkeley. The idea was to transform some land near the school into a garden and, in the process, to teach local school children about food and agriculture, to reacquaint them with the land. Because funding was unavailable, Waters asked parents and members of the business community for help.

A parcel of unused land was selected as the site of the garden, and the asphalt shell that covered it broken up and hauled away. In 1999, over 120 people came to help plant the first cover crop, which prepared the field for cultivation by adding nutrients to the soil.

The student garden staff has already enjoyed several years' worth of harvest, and has started growing an herb garden that includes tea and medicinal herbs. Agricultural practices are constantly being revised and updated. Every year the Edible Schoolyard staff attends the Ecological Farming Conference in Monterey.

In the past few years a kitchen classroom has been created. Here students learn about staple foods eaten around the world, and get a chance to transform the garden's harvest into creatively prepared meals. The cooking of food becomes a lesson in sharing ideas and pooling labor, the eating an opportunity for unhurried social interaction.

"I believe that every child in this world needs to have a relationship with the land...to know how to nourish themselves...and to know how to connect with the community around them," says Waters. The middle school students cultivate and harvest the crops, and the cafeteria buys and prepares the produce for school lunches. Waters hopes that this program will teach kids to value fresh food and value their own contributions that will bring it to the table. Eventually, she also hopes that the Edible Schoolyard will inspire a national change in school curricula. Already, other middle and high schools in California and Ohio have launched similar projects.

Alice Waters' activities and philosophy for change have been nationally recognized. In 1997, she received the Humanitarian Award from the James Beard Foundation. In 1999, the United States Department of Education Secretary, Richard Riley, honored her with a John H. Stanford "Education Hero" award. Most recently, Waters agreed to work with both the Berkeley School District and Yale University to revamp their respective food service programs.

In 2002, Waters delivered a speech at a REAP (Resource Efficient Agricultural Production) Conference in Madison, Wisconsin. Here is an excerpt of that address:

...The culture of fast food is everywhere. We’re swallowed up by it. Drive through the suburbs of any American city and what do you see? Mile after mile of franchises. It’s hard not to feel that we’re the victims of a giant conspiracy. In fact, industrial farming and fast food operate hand-in-glove, very much like a vast conspiracy. Together they suppress variety, limit our choices, and manipulate our desires by getting us hooked on sugar and salt.

And what is it that our children learn from fast food?

Number one, of course, is that food is cheap and abundant and that abundance is permanent. I’m not saying that food shouldn’t be affordable and available, but the fact is, the way we’re going, to give you just one example, California’s Central Valley is going to lose its fertility within the next twenty or thirty years! Farmers know that living soil is precious and must be cared for and replenished, and, I’m sorry, but that isn’t cheap. We all know that fast food is cheap only because we haven’t yet paid the real cost of farm subsidies, Middle Eastern oil, and depleted soil. And we’re only beginning to wake up to the health consequences of cheap food. A national diet heavy with processed foods and meat is leading to obesity and diabetes at record levels.

Fast food value number two: Resources are infinite, so it’s perfectly okay to waste. “There’s always plenty more where that came from.” This glorification of disposability is reflected everywhere in our culture. But the farmers who are here today know that if you have to dispose of something yourself, you’re a lot more likely to think twice about whether or not you really need it.

Number three: Eating is primarily about fueling up in as little time as possible: You drive in, order, pick it up, eat it in the car, and dump it in the garbage can. Food is supposed to be fast and available pretty much twenty-four hours a day. And yet we all know, or should know, that any thing worth doing takes time.

Number four: Meat, French fries, and Cokes are actually good for you. And they should taste exactly the same everywhere. Of course, by this logic, diversity is totally undesirable. But any nutritionist will tell you that what’s really good for you in any diet is variety.

Number five: It doesn’t matter where the food actually comes from, or how fresh it is. The seasons are of no particular consequence. The place you’re in is of no particular consequence. But the seasons connect us to nature; they punctuate the passage of time and they teach us about the impermanence of life — something that we haven’t wanted to look at in our society.

Number six: Advertising confers value. Publicity is a virtue. Therefore, celebrity is the most virtuous thing of all. And yet the ultimate sign of worth is when something doesn’t need any advertising at all — when everyone just gets it somehow. Can we have forgotten that modesty is a virtue?

Number seven: Work is to be avoided at all costs: There are more important things to do. Preparation is drudgery, anyway, and other people are better at it than you are. Cleaning up is drudgery, too. There are more important things to do. But the really important and deep thing about life is that you have to do things! Work is not to be avoided at all costs. We have been told that work is here, and pleasure is there; but in fact, the real pleasure is in doing. Work can feed our imaginations and educate our senses. And if you want somebody else to do that for you, you miss out on the real juice of life. Even the hard physical work we’re so eager to delegate to others can change us for the better. And if you believe that work has value, then you begin to see why making an effort to make a meal at home is a desirable thing. That’s why it’s so terrible to me when people slave away their whole lives in order to take a vacation on a cruise ship somewhere: They miss out on the pleasure that could be there everyday if only they paid attention to what they ate. Because the one thing we all have to do everyday is eat. And the rituals of cooking and eating together constitute, in the words of Francine du Plessix Gray, our “primal rite of socialization, the core curriculum in the school of civilized discourse. The family meal is a set of protocols that curb our natural savagery and our animal greed, and cultivate a capacity for sharing and thoughtfulness.”

So what about anti-fast food values? Is there a future for values that tell us that real food costs more money? That real food should be available to all of us, rich and poor? That cooking and eating are not drudgery? That concentrating on something is okay? That everything is woven together? How can we pass on to our children the magic of hospitality and generosity? How can we teach our children the values that transform our lives and the world around us? Because only slow food can teach us the things that really matter — care, beauty, concentration, discernment, sensuality, all the best that humans are capable of, but only if we take the time to think about what we’re eating.

The farmers we’re celebrating today can teach us another way of being. And our task is to apply their lessons to every single facet of our lives. It’s not enough to shop at the farmer’s market every week. It’s a start, but it’s not enough. We have to bring the lessons of sustainable farming into the schools. The public school system is our last best hope for teaching real democratic values, values that can withstand the insidious voices of those who would have us believe that life is all about personal fulfillment and personal consumption.

Life is more than that. Change the food in the schools and we can influence how children think. Change the curriculum and teach them how to garden and how to cook and we can show that growing food and cooking and eating together give lasting richness, meaning, and beauty to our lives.

The following section was added by The MY HERO Project in 2025

In October 2024, Alice Waters became the tenth person to receive the Julia Child Award, created by The Julia Child Foundation for Gastronomy and the Culinary Arts in association with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. The award, presented annually, is given to “an individual (or team!) who has made a profound and significant difference in the way America cooks, eats and drinks.”[1]

In addition to an engraved award, each winner is given a $50,000 grant for a food non-profit organization of their choice. Waters, of course, chose The Edible Schoolyard Project. Speaking to Forbes correspondent Claudia Alarcón, Waters explained how important it is to teach children about slow food.

I know for sure that when kids grow it and cook it, they all eat it. It doesn't matter what it is. It's an empowerment. […] The only place that you can really teach a lot of people something else; I mean we can't expect that we're going to make change if we don't teach in school.[2]

[1] https://juliachildaward.com/award/

[2] Alarcón, Claudia. Alice Waters Receives Julia Child Award And $50,000 For Edible Schoolyard [Online] Available https://www.forbes.com/sites/claudiaalarcon/2024/10/31/alice-waters-receives-julia-child-award-50000-for-edible-schoolyard/. 2024.

Page created on 6/9/2004 3:36:55 PM

Last edited 3/3/2025 4:35:44 PM