|

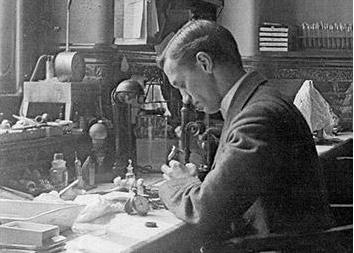

| Alexander Fleming working at St. Mary's Hospital. (www.nytimes.com) |

In today’s increasingly hygienic conscious world, antibiotics and disinfectants are everywhere. Take a walk on the streets, and countless bottles of sanitizer can be seen hanging from backpacks and duffel bags. Antibiotics for infections are easily accessible at the local pharmacy, while doctors administer thousands of shots each day to treat and cure cases of bacterial disease that would have been fatal less than 80 years ago. A world without antibiotics is almost impossible to imagine, but that was the unfortunate case for the first half of the twentieth century, where simple infection was responsible for a large number of deaths. Were it not for the discovery of penicillin by immunologist Alexander Fleming, the world might be as susceptible to common bacterial infections now as it was less than a century earlier. His discovery of a substance that would in the future save millions of lives was by itself hero-worthy, but Fleming contributed far more to the world. Alexander Fleming’s modest, selfless personality and humanitarian motivations fueled an unwavering dedication to scientific research and yielded results that not only revolutionized the field of medicine, but inspired it, and solidified his position as a hero.

The seventh of farmer Hugh Fleming’s eight children, Alexander “Alec” Fleming was born on August 6, 1881, in Lochfield, Ayrshire, Scotland. He spent much of his early years out exploring and working on his father’s farm, honing observation skills that would prove invaluable to his future career. Alec started attending a local school at the age of five, and at age 14, after his father’s death, traveled to London to live with his ophthalmologist brother. When his uncle died and left him a sizable inheritance, Alec resolved to follow his brother and enroll in medical school. Despite his limited early education in rural Scotland, Alec scored at the top of the entrance exams after less than a year with a private tutor. He decided to enroll in St. Mary’s Hospital Medical School, and won a scholarship that entirely paid for his tuition. Alec’s enjoyment for competition would place him at or near the top of all his classes, and earn him numerous prizes. In 1906, Fleming, unsure of what specialty he would settle on, joined St. Mary’s Inoculation Department, where he ended up staying for 49 years. During World War I Fleming served in the Royal Army Medical Corps, focusing on the use of antibiotics to treat the numerous wounds and infections he encountered. On leave from the army in 1915, Fleming married Sarah Marion McElroy, and they had one son named Robert. After the war, Fleming devoted his time to discovering an antibiotic that could destroy infection once it had entered the body. He encountered his first antibacterial agent, lysozymes, in 1921, but it was in 1928 that he made his most famous find. It was penicillin, a discovery that would earn him the Nobel Prize in 1945 and bring international fame. Consequentially, Fleming was internationally mourned when he died on March 11, 1955 at the age of 73 after a heart attack. His ashes were interred in the crypt of St, Paul’s Cathedral in London, the place where many of England’s other heroes have been laid to rest.

|

| The original penicillin mold. (3fortheroad.blogspot.com) |

During an era of war and depression, Fleming’s personal motivations and self-effacing personality played a huge part in the public’s acknowledgment of him as a hero. In October of 1914, Fleming temporarily suspended his research at St. Mary’s to serve at a British hospital in France. Fleming, along with his mentor and colleagues, studied the wounds and infections of injured soldiers, and the effects of antibiotics on such injuries. He discovered that the antibiotics being used had little positive effect on the wounds, and even caused harm by incapacitating the body’s immune system. Fleming’s other revelation: more soldiers died from simple secondary infections than from the actual war injuries themselves. After World War I ended, Fleming resumed his research with new determination. “He was particularly motivated to find an effective yet safe antibacterial substance after witnessing the horrible suffering caused by bacterial infections during the war. Fleming remained convinced that an ideal bacteria-fighting agent could be found that would destroy the invading bacteria yet not harm the body's own white blood cell defenses” ("Fleming, Alexander (1881-1955)."). Fleming’s firsthand experiences had shown him just how lethal and painful bacterial infections could be, and just how useless the antibiotics being applied during the war were. His benevolent and persevering nature was a part of what pushed him to find an antibiotic that could alleviate the agony and death caused by infection. Even after the sale of penicillin had saved thousands of lives “Fleming never collected royalties on penicillin. In 1945 he received the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine and toured the United States, where he was hailed as a hero. American chemical firms collected $100,000 and presented it to him in gratitude for his contribution to medical science. He refused to accept the money personally but used it for research at St. Mary's” (Kauffman). Fleming’s hard work and dedication had garnered him global renown. The money being offered was more than enough for his family to live comfortably for the rest of their lives, and no one would have faulted him for taking it. However, Fleming decided to sacrifice it in favor of helping others. By donating that substantial amount to research, Fleming gave scientists additional chances to discover drugs and antibiotics that could benefit the world like penicillin did. It was an utterly selfless move on his part, one that did not go unnoticed by the public. “All the self-important characters had brought death and destruction. What greater contrast could there have been in Fleming? … When they [ordinary people] actually saw, not a dominating, alarming figure, but a simple, modest man, they went wild with gratitude and affection” (Lax 254). The discovery of such a revolutionary substance like penicillin was enough to make Fleming a hero in the eyes of the world, but his shy, modest reaction to his newfound fame and continued acts of goodwill completely endeared him to them too. He had proved to a war-weary world that not all heroes were like the dictators and military leaders that had dominated the recent World Wars, and that not all science created during the Wars was destructive.

Although the discovery of penicillin was his crowning achievement, it took Fleming many years to unearth it, and during that time, he made many other contributions to science and humanity. While on the frontlines in France, Fleming devised simple but revealing experiments about the antibiotics in use by the British army at the time. “Some authorities believe that he never conceived anything more perfect or ingenious than these brilliant experiments by which he demonstrated the danger to human tissues of incorrectly administered antiseptics” (Kauffman). Overshadowed by his later find of penicillin, these experiments provided a clear reason as to why antibiotics that had worked in previous wars now failed to produce a similar effect, and also how they harmed more than they helped. Fleming demonstrated how jagged wounds in flesh provided a place for bacteria to hide, and also how medicine only destroyed the top level of bacteria and the body’s white blood cells before being swept away. This research saved lives, forcing doctors to change their methods of treatment to more effective ones. Besides demonstrating the harm of incorrectly used antibiotics, “with his colleagues from St. Mary’s Hospital in London, the genial Scot [Fleming] had devised new treatments for bullet and shrapnel wounds, ways to prevent and limit infection through sanitary surgical procedures and dressings” (Haugen 63). This was especially important, because without a clearly defined method to follow, some doctors would revert back to the former process of treatment, which could actually produce worse results than when the wound was left on its own without any administering of antibiotics. Perhaps Fleming’s new treatments for the soldiers wounded in World War I weren’t as effective as penicillin, but they still saved lives, and are a mark of his skill and perseverance with limited resources. World Wars I & II were not kind to scientists, especially immunologists like Fleming. “It was an era when physicians had few weapons to fight disease; when experiments were carried out with crude, often homemade instruments; when financial gain was not a driving force of science; and when a scratch from a rose thorn could start a downward spiral to death” (Lax 6). Yet despite these conditions, Fleming was able to discover what researchers today with millions in their budgets and top-of-the-line equipment are struggling to do: find a drug that can transform the world.

|

| Penicillin inhibiting the growth of bacteria. (www.britsworldwide.org) |

After his discovery of penicillin, Alexander Fleming urged and inspired others to refine and continue his work, which opened countless doors for the advancement of antibiotics. Although it is true that Fleming discovered penicillin, he lacked the necessary chemistry background to purify and stabilize it into the injections that were used near the end of World War II to save thousands of soldiers’ lives. However, despite his own failures to extract and concentrate penicillin, Fleming was convinced of its potential, and wrote a paper on it detailing its possible effects so others could succeed where he had failed. Ten years later, Howard Florey and Ernst Chain, the head of the Oxford team, were “inspired by a paper the immunologist had written, and starting with a sample of penicillin Fleming provided, they found a way to purify and preserve the invaluable substance ― the first antibiotic ― for medical use” (Haugen 66). The Oxford team’s results were mass-produced in 1943 for military use, and then in 1944, civilian use. Fleming also pushed for the refinement of penicillin because “before penicillin, the few drugs that were available to fight bacterial disease were inefficient and highly toxic to the human body” ("Fleming, Alexander (1881-1955)."). The problem was that scientists hadn’t been able to find anything that could quickly and efficiently kill bacteria without leaving the body’s cells intact, and had been forced to result to dangerous compounds that killed both bacteria and flesh indiscriminately. At the time Fleming discovered penicillin, many scientists, including Fleming’s own mentor, had considered the search for an effective antibiotic an inefficient and pointless use of effort that had no future. Penicillin was light-years ahead of any existing antibiotics in the 1940s, and completely changed scientists’ opinions about antibiotics in general. Furthermore, this discovery provided a foundation for others to develop antibiotics similar to penicillin, since it didn’t work against every bacterium, nor could every patient’s body accept it. “Fleming devoted his life to helping humanity by trying to figure out how to fight infections. He did not invent penicillin, and, in fact, he was not the first to discover it, …but Fleming was the first to recognize its broad significance and to draw attention to it” (Cullen 117). Fleming’s actions and achievements still inspire scientists today in their quest for new medicines by demonstrating that it is not always what you find that matters, but how you treat this discovery that makes a difference.

According to André Maurois, “No man, except Einstein in another field, and before him Pasteur, has had a more profound influence on the contemporary history of the human race” (Kauffman). Without Alexander Fleming’s discoveries, we might still be struggling to eliminate infection from simple cuts that thanks to him can now be cured with a simple shot or swab of antiseptic. His perseverance in researching antibiotics saved countless lives and ended needless suffering, especially during the World Wars. Additionally, penicillin has lead to the creation of variant medicines that combat a variety of diseases. Fleming proved himself a hero with not only groundbreaking medical work, but also a compassionate, unassuming persona and a commitment to improving the lives of humankind. His contributions to medicine remain largely unsurpassed, and an inspiration for each new generation.

Page created on 5/20/2010 12:00:00 AM

Last edited 5/20/2010 12:00:00 AM