|

| (worldmag.com) |

You start out with the essential stories, the ones that reach to the heart of things.

For my young children, this meant first of all Bible stories—especially those bold bright Old Testament stories like Cain and Abel, Noah and the flood, Moses, David and Goliath, and of course the stories of the Nativity and Calvary in the New Testament.

I judge books for small children on their covers—and on their illustrations. The words I can supply, based on my child’s vocabulary and interest level. This was also how I approached the other classic story lines and characters I wanted to pass on to him or her from fairy tales and classical mythology. At first, I worried my children would be puzzled about the differences between the Greek and Roman gods and the God of the Bible, but there was no problem at all. I explained that the myths were stories people made up because they didn’t know about the real God, and my kids found this perfectly reasonable. Children usually know what their grown-ups believe to be true and important.

But how heroic were the people in these stories? How good an example of heroic virtue does Jack (of Beanstalk fame) provide, or Jason and the Argonauts, or even Jacob and Esau? There are a lot of knaves and fools in these time-tested stories, but even these characters teach lessons our children may not learn if their diet is restricted only to warm fuzzy books about little suburban children like them.

First, knaves and fools face consequences of heroic proportions. Esau loses his birthright and his place as a patriarch, while Jacob lives in exile for years, getting snookered into working away his prime for dear old Uncle Laban. Lot’s wife turns into a pillar of salt, and there’s nothing to be done about it. Paris steals Helen and starts a ten-year war. Red Riding Hood ignores her mother’s advice and gets her grandma swallowed by a wolf.

Life is lived on a grand scale in these tales. One man’s obedience to a call from God leads to his fathering descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky. The hapless miller’s daughter in “Rumpelstiltskin” becomes a queen but almost loses her child to a wicked dwarf. Hercules performs gargantuan labors in atonement for horrifying crimes.

An enterprising courage and an optimistic spirit characterize the successful heroes: David confidently striding toward the giant Goliath, Jack making repeated trips up the beanstalk to the giant’s lair, Theseus setting forth to slay the hideous Minotaur holed up in the Labyrinth. Many of these characters also triumph through cleverness and even trickiness, as Ulysses does in devising the Trojan Horse, but using one’s wits is another lesson we should like our children to learn, soon after courage.

|

And kindness. The best of these stories demonstrate characters caring for the widow and orphan. Many of Grimm’s fairy tales feature several sons setting off separately on a quest to gain a treasure or win an inheritance. The arrogant older brothers inevitably cheat or walk over anyone poor or weak in their path, while the underrated youngest son responds to those in need, generously shares whatever he has, and earns valuable help in his quest thereby. (Tales of King Arthur’s knights and other old legends also pick up this theme, combining it with lessons on how deceptive appearances can be—in the dangerous regions around Camelot, old hags often turn out to be bewitched, and a beautiful woman may lead you to your doom.)

|

Clear consequences for one’s actions, the value of courage, optimism, ingenuity, and kindness—these are all things we want to convey, preferably in a captivating, non-preachy way, to any child we hope may grow to heroic stature, or at least learn to appreciate the heroes around him.

As my own children grew older, I began to search out stories that would reinforce all those lessons with a similar sense of large destiny and firm consequences. These “read aloud” stories, now read to children beginning to be old enough to read themselves, had to be well-written, too. By popular demand, we went through C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia several times. Lewis’s ordinary schoolchildren are challenged to become extraordinary players in the fight of good against evil. Loyalty, generosity, owning up to faults, playing by the rules, performing brave acts even when you don’t feel brave, risking unpopularity, telling the truth—all these aids to heroism are presented in the best possible way, through an enchanting artistic vision.

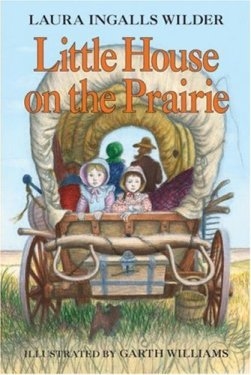

The best pioneering tales also combine excitement with weighty lessons. Despite all the female characters in the Little House on the Prairie series, my son loved those books (which lack the syrupy sweetness of the ’70s TV show). They are filled with deadly blizzards, encounters with wolves and bears, sickness, tornadoes, prairie fires, and so many agricultural disasters that you wince every time someone mentions how good the wheat crop looks. Without making a big deal about it, the Ingalls family all know that you work hard, carry your own weight, never complain, and keep ready to think fast in emergencies. This is the John Wayne school of heroism.

Swashbuckling books like Treasure Island or The Three Musketeers or Robin Hood or King Solomon’s Mines or Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World or, later, Sir Walter Scott and his imitators have much to offer as well. The characters need not—and in these kinds of stories, probably should not—be paragons of virtue, but they must be courageous when it counts, be loyal to friends, benefactors, and country, and be willing to subject themselves to principles even when expediency would pay better.

Traditional parents who aim to provide more than self-absorbed mediocrity for their children will have their own lists of good books for kids—alternatives to Judy Blume and her like. What matters is not tracking down every title on someone else’s list, but recognizing the right stuff when you see it, and then getting it into the minds of your children. Homeschooling book catalogues carry many excellent titles, including G.A. Henty’s historical fiction, brought back into print, and Jules Verne’s books. Used bookstores and older libraries conceal wonderful finds amid the dreck. Many bookstores with large children’s sections shelve Caldecott- and Newberry-award-winning books separately, and if you look through these with a little care you can find some non-trendy, beautifully written examples of historical fiction or fantasy.

You may have noticed how many authors implicitly acknowledge the difficulty of presenting heroism in the here and now by setting their heroes in other places and times. Madeline L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time series, for example, repeats many of the same lessons of courage, loyalty, self-reliance, and daring to be different in space-time travel. Frances Hodgson Burnett is well known for her The Little Princess and The Secret Garden. But she also wrote a riveting boy’s adventure story called The Lost Prince, full of patriotic spies, mythical East European kingdoms, hairbreadth escape, and nobility masking itself in the commonplace.

|

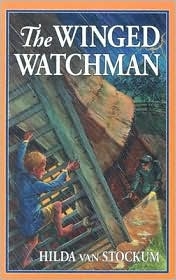

Then there are new, or relatively new, finds, like the recently re-issued books of Hilda van Stockum, who wrote during and after World War II. Though most of her books are enjoyable novels of family life, one—The Winged Watchman—is set in occupied Holland during the Second World War. A Dutch boy aids a downed British pilot and attempts to foil a nest of informers who live nearby. This is a powerful story which is not afraid to make its readers share pain as well as suspense and exhilaration.

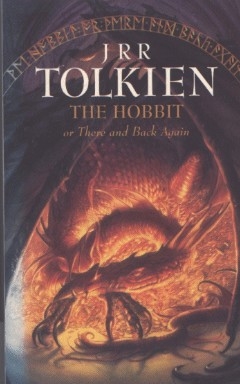

One day, after we had gone through the Narnia stories for the third or fourth time, my son asked, “Aren’t there any other books like that?” I decided it was time to try him on Tolkien’s The Hobbit, which, though not quite “like that,” breathes the same air. He was ready for Tolkien’s mix of the heroic and the mundane in Middle Earth, where a commonplace hobbit summons up courage he didn’t know he possessed and learns to hold his own against dwarves, elves, dragons, and goblins. Next I gingerly tried out The Lord of the Rings, not sure whether my son was old enough to appreciate the denser world and higher stakes of this successor to The Hobbit. He loved every page of it, including the appendices on the origins of elvish language.

|

All this is not so much a reading list of “heroic” literature as a touchstone to help parents know how to recognize it. In a haphazard way I looked for stories that were large—that opened up a spacious world of ideas, adventures, and opportunities; sparked the imagination; conveyed the sense that life held manifold opportunities, that actions provoked consequences, but second chances and rebirths might turn up at the bend of a road; that courage, perseverance, loyalty, ingenuity, and kindness somehow accord with the laws of the universe, and thus have their own built-in success mechanisms for either the short or the long term.

Success does not always mean glory, monetary gain, or even survival, as the martyred head of the Dutch resistance in The Winged Watchman attests. It means something closer to achieving rightness, maturity, the purpose for which we are born. Blood-stirring martyrs’ stories bring this point home, as do patriots like Nathan Hale. Though most characters do not achieve that standard of heroism, the ones you remember and admire are usually willing to pay a heavy price for great goods.

Page created on 11/20/2011 11:27:40 AM

Last edited 4/19/2024 6:40:06 PM