|

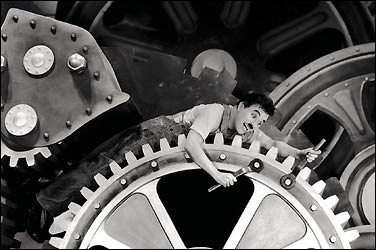

| Chaplin in Modern Times (http://www.wilsonsalmanac.com/book/apr16.html) |

In a poor home of a performer in a poor section of London during the late 19th century, a child was born into a dim life filled with tragedy. His mother was mad, his father dead by alcoholism; most people in today's society would write this child off, and indeed most did. Who knew that this child would be Charles Spencer Chaplin, the first ever cinematic genius?

|

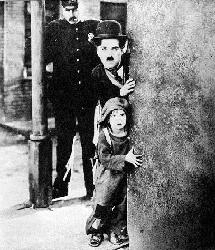

| Charlie Chaplin in The Kid (vatzhol.club.fr/chaplin2.html) |

Most of Chaplin's early life was spent moving from room to room while his family struggled to pay the rent and stay fed. His mother made enough money to survive as a performer, but she consistently suffered spells of madness and was admitted to mental institutions on many occasions. Alas, her performing career withered away, along with the family's funds. In his autobiography, Chaplin describes his mother's next attempt to support her family through sewing clothes; but this eventually ended when they could no longer afford to rent the machine. In his life, the results of poverty were broken up only by off-and-on residency in workhouses for homeless children, and these were the times when his mother was in a mental hospital. It truly is amazing that one of film's greatest comedians came out of such a tragic background, but at the same time it seems quite typical. Charlie Chaplin teaches us that sometimes, in the face of adversity, one must simply laugh.

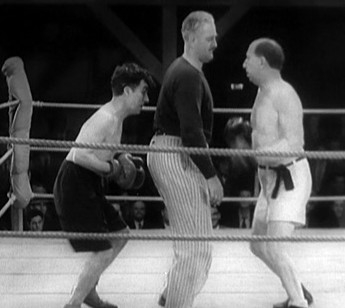

Though you cannot judge a man's merit based on something he does for more money than any four men could spend in a lifetime (for example a professional athlete), Charlie Chaplin's silent movies could be understood anywhere in the world because they are just that; silent. While talkies strengthened the language barrier, Chaplin's movies remained silent so that the whole world could join in on the laughter. As America was enjoying early talkies like The Jazz Singer, America and the rest of the world were roaring and crying at City Lights.

|

| Charlie Chaplin in City Lights (www.geekroar.com/2003/11/) |

As his movies began to criticize society more and more, the government started to get involved. They felt they were losing their power to some clown who made fun of them. Out of fear, they labeled Chaplin a Communist, which of course was like naming someone a witch in 17th century Salem. Chaplin responded with one of his greatest masterpieces, Modern Times, where he even criticized the fact that he had been labeled. There is a particular scene that shows a factory workers' strike and they're parading down the street, and Chaplin sees that someone has dropped a flag (assumed to be red) and picks it up, and the police arrest him, claiming him the Communist leader of the strike. Eventually, the U.S. government couldn't bear to have him in their country, so much so that when Chaplin left the United States for England to promote his newest film, Limelight, they revoked his return permit while he was at sea, thus barring his entrance back. Without batting an eyelash, Chaplin simply moved to Switzerland and spent the rest of his days there.

In 1972, Chaplin was invited and welcomed back to the United States to receive a special lifetime achievement award, but still resided in Switzerland where he died Christmas Day 1977.

This essay doesn’t exactly describe a hero who flies, or saves lives, or fights for his country. To see an artist as a hero takes some abstract thinking. By keeping his movies silent long after other studios had moved on, he kept the world connected for that much longer, but he also ignored the mainstream and kept doing what he thought was best for the industry, and evidently for himself, considering that three of his silent films, City Lights, Modern Times, and The Gold Rush are listed on the American Film Institute’s list of the 100 greatest films of all time. Also, he stayed his course when he faced political scrutiny for some of the ideas portrayed in his films. And last but not least, he rose from his almost doomed childhood and became one of the most recognized, and one of the richest, faces in the world. Sometimes a hero can come in the form of a "little tramp."

Page created on 5/1/2007 12:14:50 PM

Last edited 2/24/2025 5:30:58 PM