|

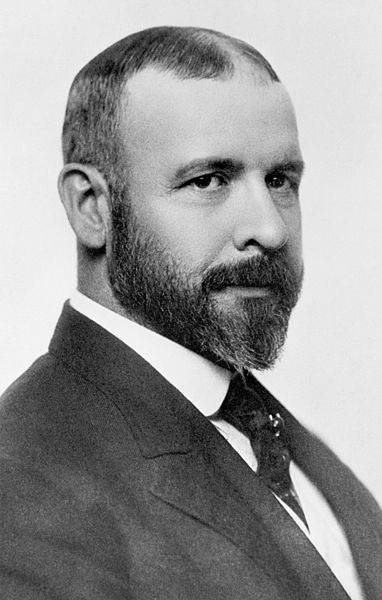

| Louis Henri Sullivan Unknown author / Public domain via Wikimeda |

Have you ever looked at the skyline of Chicago or New York or San Fransisco and imagined what it would look like without its tallest buildings? There was a time not long ago when these famous skylines looked very different than they do today. Louis Sullivan, an architect who worked at the turn of the twentieth century, is responsible for them. He is commonly declared the inventor of the modern skyscraper.

Louis Henry Sullivan’s parents were immigrants: his father, Patrick Sullivan, came to America from Ireland in 1847. His mother, Adrienne List, left Switzerland with her family in 1850 and arrived in Boston that same year. Both of them were artistically inclined: Patrick was a dancer and a teacher of dance, and Adrienne was an accomplished pianist and painter. Between them they would have two sons, both of whom would become architects. Their younger son, Louis, would enjoy several years of fame during his lifetime and even be credited with “inventing” the modern skyscraper.

Louis Sullivan decided upon his career when he was only twelve years old. He saw a well-dressed man walking out of a building in downtown Boston and discovered that, as Robert Twombly writes, he “was an architect, that many structures had architects, and...they invented buildings in their heads and bossed everyone else on the job.” After this experience, Sullivan never had any goal but to become an architect, and since he was already a hard-working student, he was able to achieve his goal in a very short time. He left high school early and entered the newly founded Massachusetts Institute of Technology as a third-year student. After finishing his degree, he went to Europe to study for one year at the Ecole de Beaux-Arts in Paris and to explore the art of Italy. By age twenty-five, he was a junior partner at Adler & Company, an established Chicago architecture firm headed by Dankmar Adler.

|

| Wainwright Building Library of Congress / Public domain via Wikimedia |

Chicago was the perfect place for Sullivan to set up shop for two reasons. First, the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, devastating as it was, gave architects an opportunity to rebuild. Second, the original buildings had been placed directly upon a marsh, and city officials decided to build the city a few feet above ground level to mitigate prior problems of sinkage, bad smell, and mosquitos. So even buildings that survived the fire needed to be renovated or razed and rebuilt.

Sullivan’s strength was in adorning structures with expressive ornaments and facades in the Beaux-Arts, or Art Nouveaux style. He had been drawing such decorative motifs since he was a boy, and now began designing decorative additions to the great buildings that Adler designed, structures that received immediate acclaim such as the Auditorium Building and the John Borden block and residence. When he began, Sullivan was obliged to take on residential design work for money and exposure, but as his reputation grew, he gradually dropped house design in favor of commercial buildings, which he had always preferred. By 1886, Sullivan and Adler were famous. Sullivan had become a full partner in the firm, which was now called Adler & Sullivan, and they had hired a new assistant, a young aspiring architect named Frank Lloyd Wright.

“Sullivan is regarded today as one of the most innovative architects of the developing modern period. He replaced the standard classical ornamentation of the day with highly original, organic architectural details inspired by nature. One of Sullivan's most notable contributions was the creation of a form appropriate to the tall commercial office building. Rather than stressing the horizontal layers of each story, he emphasized the vertical rise of these buildings. Verticality was made possible by steel frame construction and the use of light materials such as terra cotta, which had a malleability appropriate for carrying out his ornament” (From the MIT e-gallery website).

Adler and Sullivan designed the Transportation Building for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Working in his own independent practice, Sullivan was responsible for the Schlesinger & Mayer Store, the St. Louis Hippodrome, the Holy Trinity Cathedral, the Island City Amusement Park in Philadelphia, and many other buildings in the Midwest and around the country. He also is responsible for much of the funereal architecture and non-architectural designs, such as magazine covers and decorative motifs on award medals and certificates.

Biographer Robert Twombly wrote:

Louis Sullivan was an artist whose medium was building, a poet whose materials were stone, brick, and mortar. His work was intended to convey messages about life in his times, about democracy, business, selected institutions, human relations, nature and the physical world, but above all about the process of creation.

Page created on 6/4/2004 2:19:26 PM

Last edited 8/30/2021 8:04:30 PM