|

| Professor Leslie Thompson (Jonathan Cohen) |

Leslie Thompson is Director of the Interdepartmental Neuroscience Program at the University of California, Irvine. She has devoted her career to a very important goal – fighting Huntington's Disease.

Huntington’s Disease (HD) is a terrible disease of the brain. It can start at any time. At first, it looks like a person with the disease just has problems with his mind or that he has problems with his limbs moving when he doesn’t want them to. As Huntington’s worsens, the motion and thinking problems become more severe, until the person cannot take care of himself anymore. What is worse is that the person is completely aware of what is happening, even as the disease robs him or her of speech, control, and thought. HD is not passed on by germs or viruses; it is passed on from parent to child, when the child inherits the parent’s genes. If one parent has the gene for HD, there is a fifty percent chance that the child will get it.

There is no cure yet for HD, nor is there any way to make it better. This was the challenge that Leslie Thompson faced when she began her scientific career. She wanted to make a difference by working on a genetic disease that affected people; coming out of graduate school, she was an expert on genes and proteins, and she wanted to put her knowledge to good use.

|

| The Huntington's Disease gene (Cell, Vol. 72, 971-963. March 26, 1993,) |

When Leslie got her PhD, scientists didn’t know which gene caused HD. Scientists from all over the world worked together to find it. Leslie picked a gene, and set about finding out whether it was the gene for HD. As she was working, she shared all the information that she got with the other scientists; it didn’t matter to her whether she would get the credit for finding the gene or somebody else would. All that she wanted to do was to look at the gene as carefully as she could. Leslie didn’t find the gene. The honors went to a team from Harvard University. However, she had found out something interesting about her gene. Her gene, which she went on to study further, was one that, when it’s not right, can cause people to become dwarves.

|

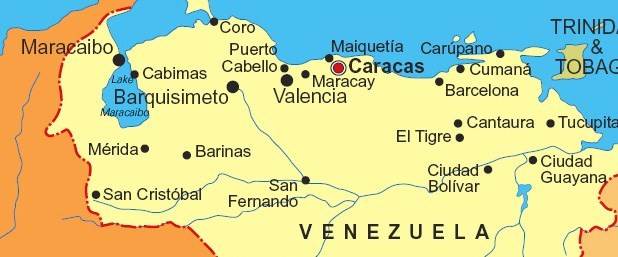

| Map of Venezuela (maps.com (licensed)) |

In order to find the gene, she and her friend Nancy Wexler, of the Hereditary Disease Foundation, went to Venezuela, in South America. In 1979, Dr. Wexler had discovered that in one city in Venezuela, HD happened four times as often as it does in the United States. Since the disease is passed from parent to child, it does not spread through infection, as a germ-based disease does. So how could it have spread to the city? The answer is that the disease was in the genes of one family of fishermen, who caught fish on Lake Maracaibo. The fishermen had wives and children, but they had a very close family, and sometimes the children married each other as a result. This meant that the gene was concentrated, and, as the family grew larger and moved to the city, more and more of its descendants showed signs of the disease. The family grew larger still and so many of its members had the disease that scientists began to notice it. Leslie wanted to help, and went with Nancy to collect blood samples from this family because it was likely that if they could find out what all the samples had in common, they could find the gene.

Nancy and Leslie had many adventures together with other scientists in Venezuela, driving around in their Jeep. It was very hot and humid there, which was difficult for them to get used to. In Venezuela, people read the traffic signals a different way; they believe that the green light means that they can go fast, a yellow light means that they can go faster, and a red light means that they can go faster still. So the scientists had to drive very skillfully in order to get around the city. After dark, things got even worse, because they had to ask directions of everybody they met, and some would tell them to go a little this way and others would tell them to go a little that way and, by the time they were done, they might be at the border of Colombia without having found the family they were after. It was very lucky that Leslie spoke Spanish; otherwise, they might have gotten completely lost. They lived on a diet of Doritos, Coca Cola, and, occasionally, Spam. But they were not there for fine dining. Every family with HD they met helped them narrow down the search for the gene, and the group visited as many of them as possible. In the end, they found an important truth about the gene: the HD gene is the same worldwide, so the cure is going to be the same worldwide.

Leslie had to undergo many hardships and difficulties in her life to become the famous scientist that she is today. When she was barely out of graduate school, she worked in the lab of Dr. John Wasmuth, who was studying a gene that would turn out to be the one for HD, and who was one of the most important people in the grand international collaboration to find the HD gene. In 1995, Dr. Wasmuth died young, at age 49, in the middle of his work. Before anyone could come to terms with his death, Leslie had to take steps to ensure that his laboratory would continue to survive. Government agencies and private foundations had given money to the laboratory to do its important work, and that work needed to continue. Together with another scientist in Dr. Wasmuth’s lab, Leslie made sure that the laboratory kept on going where it had left off, and that the network of people who had helped the laboratory and its members stayed in place. For a young scientist like Leslie to do that meant that she had to pour as much time into keeping the lab going as into the work going on in it – dedication that took up every waking hour she had.

Another challenge for Leslie was when she decided to have children. For women scientists, the decision to have or not have children is a very difficult one, because the time that they spend on their children is time taken away from their laboratory work. Leslie not only decided to have children, but she took three years off when they were young to help them with growing up. Taking time off from a young researcher’s career could make it impossible for her to achieve her goals of success, but Leslie stayed current with research and, when she came back, she succeeded.

Leslie has tried to bring some of the insights she has gained in the laboratory into the larger world, to the community of HD patients and their families. For HD patients, hope is in short supply. Over the course of their already shortened lives, they find themselves able to do less and less, unable to control their minds and bodies. The rate of suicide is high; the rate of suicidal thoughts is even higher. Leslie is uniquely qualified to tell these patients and their families that there is, indeed, hope – that there is a community of researchers around the world trying as hard as it can to help them. She sits with them, she talks to them, and, sometimes, she hugs them. She says, “They are like family; I have to take care of them, I have to help them.”

Page created on 4/13/2013 3:24:08 PM

Last edited 1/9/2017 10:36:10 PM

Andrich, Juergen. "HUNTING for Answers." Scientific American . 2006. 17.2, pp. 70-75

Seppa, N.. "Huntington's Advance." Science News. 2003. 163:7, p. 102

Cattaneo, Elena. "The Enigma of Huntington's Disease." Scientific American. 2003. 287:6, p.92