|

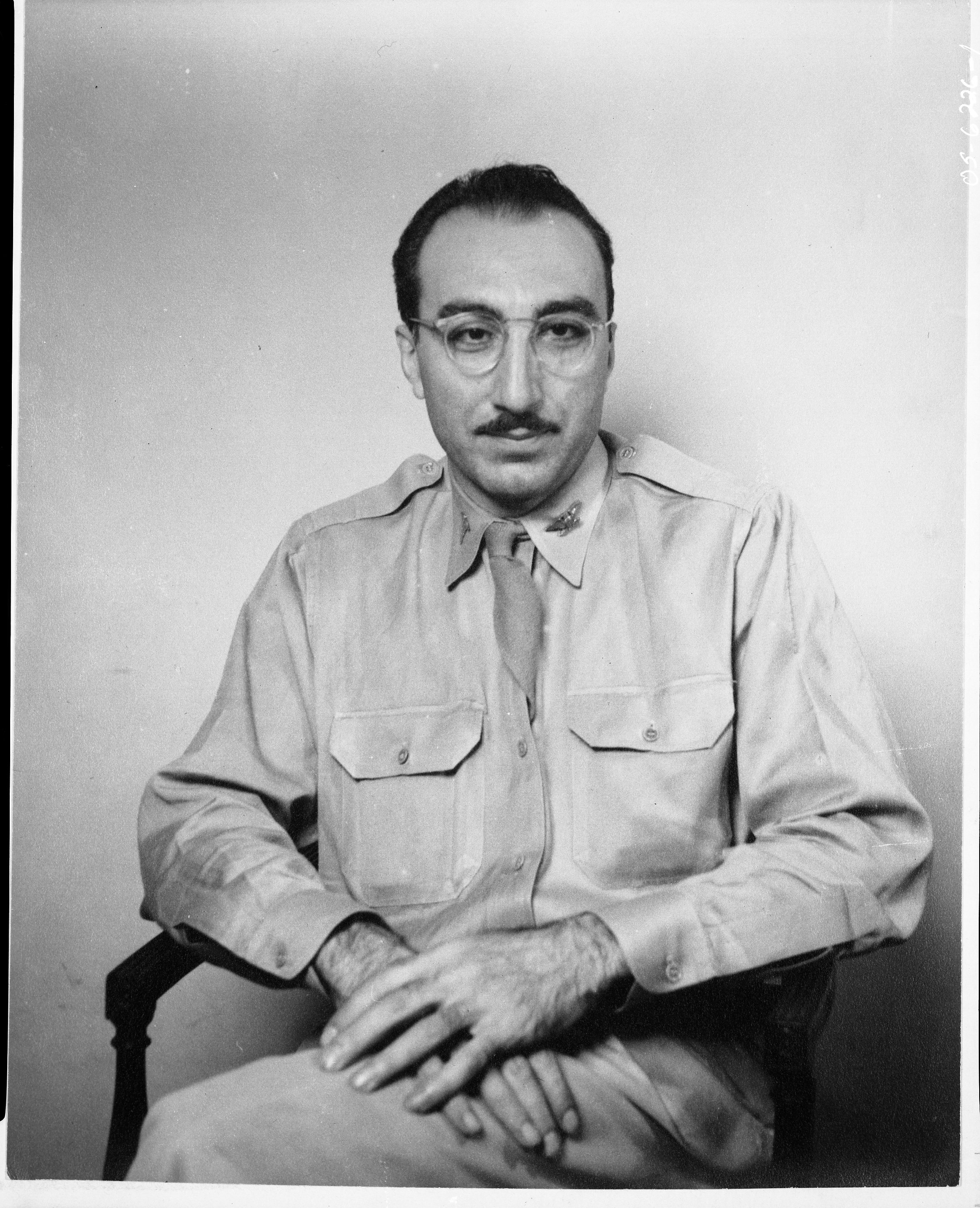

| Dr. Michael DeBakey Otis Historical Archives of “National Museum of Health & Medicine" (OTIS Archive 1) / CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia |

In July 2008, Dr. Michael DeBakey passed away just months from his 100th birthday. His contributions to the field of medicine will have spanned the better part of 75 years. He's a Health Care Hall of Famer and a Lasker Luminary. He's a recipient of The United Nations Lifetime Achievement Award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom with Distinction and The National Medal of Science. He was given the Lifetime Achievement Award of the Foundation for Biomedical Research and in 2000 was cited as a "Living Legend" by the Library of Congress.

It's like this with Dr. DeBakey. Seventy-five years of firsts and foremosts, achievements and awards. His list of accomplishments is so utterly titanic, his resume requires an intermission, a bit of time for the reader to stretch his legs and refuel for the second half. But if you stick with it, you'll find that taking a closer look at the father of modern open-heart surgery reveals something alive and loving and altogether miraculous: his heart.

The year was 1932 and Michael DeBakey had just developed the roller-pump, ultimately making the heart-lung machine feasible and paving the way for open-heart surgery. This awesome accomplishment would soon be followed by another milestone in Michael's life: graduation. DeBakey was just a med-school senior when he set about solving the design problems inherent in a mechanical blood pump. Confronted with what was essentially an engineering challenge, DeBakey did something that few med-school students would consider, much less admit: he went to the engineering library. It would be the first of a number of interdisciplinary advances made possible by Dr. DeBakey, advances that include the development of Mobile Army Surgical Hospital units, Dacron artificial grafts, the artificial heart and interactive telemedicine.

Medical historians will, no doubt, look to Tulane Medical School and Dr. DeBakey's development of the roller-pump as the beginning of one of the most prolific careers in modern medicine. But ask Dr. DeBakey where it all began and the doctor points to an altogether different institution of learning: his home. "My parents were highly intelligent, industrious and altruistic. They valued education and believed strongly in the individual's need to reach for excellence and to contribute to society. They not only lavished love and support on their (five) children, but provided generously for our full education."

As if to return the favor, Dr. DeBakey would finish his traditional pre-med and medical school training in just six years instead of the normal eight. Within five years of graduating from Tulane Medical School, Michael DeBakey the student would become Dr. DeBakey the teacher by joining the faculty of his alma mater. The role of teacher is one that DeBakey has played ever since. In 1948, Michael E. DeBakey, M.D. became the Chairman of Surgery at Baylor College of Medicine. In the decade following his arrival in Houston, the doctor campaigned to create a partnership between the college and a network of Texas Medical Center hospitals. This would eventually allow Baylor graduates to remain in Houston to continue their training, instead of seeking out residencies elsewhere. It was an innovation that improved the education offered to the residents and, in turn, improved the quality of the doctors. And those are the accomplishments that mean the most to Dr. DeBakey. "I take pride in the outstanding surgeons I've trained who have returned to their homes throughout the world to provide the best available healthcare to their patients."

In the 1940s, he was assigned to the U.S. Surgeon General's office. In 1945, Dr. DeBakey was awarded the Legion of Merit for developing Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals for the treatment of the wounded during wartime. Better known as M*A*S*H units, these field hospitals were staffed by mobile teams consisting of a surgeon, an assistant surgeon, an anesthesiologist, O.R. nurse and technician. Instead of sending the wounded back to the base for medical treatment, M*A*S*H units took the medical treatment to the front. The time it took before wounded soldiers could be treated was drastically reduced and, as a result, countless lives were saved.

In light of heroic accomplishments like these, one might expect Dr. DeBakey's own heroes to be larger-than-life figures taken from the pages of history. But on the subject of heroes, Dr. DeBakey reveals that even a titan in the field of medicine isn't so different from you or me. "[There have been] a number of people," the doctor says, "whose feats of courage or nobility of purpose have inspired great admiration, but my first and lasting heroes were my father and mother." His parents were Lebanese immigrants Raheehja DeBakey and Shaker Morris, and Dr. DeBakey attributes his 70-plus years of service to their teaching by word and example "the highest principles of honesty, integrity, compassion, service and altruism." Though the doctor scoffs at the notion that his Lebanese heritage ever served to impede his ascent to the most respected echelon of medicine, there can be no doubt that his traditional Christian upbringing still reverberates in his thoughts and deeds. “The traditional values of honesty, integrity, compassion and service are still relevant. I believe all of us should strive to make some contribution, however small or grand, to society and should observe The Golden Rule (do unto others as you would have them do unto you) in living our lives. If that rule were universally observed, we would have attained that precious goal – peace.”

The 1950s and 1960s were a busy time for Dr. DeBakey. Employing the same problem-solving approach he used in developing the roller-pump, he introduced the Dacron and Dacron-velour artificial arteries that he had initially developed on his wife's sewing machine. In 1953 he performed the first removal of blockage from a carotid artery. Three years later, he performed the first patch-graft angioplasty. In 1960, he began development of the artificial heart and in '63 he was the first to use interactive telemedicine. In 1964 he performed the first aorto-coronary artery bypass and two years later was the first to successfully use an artificial heart. When asked which of his contributions gives him the most hope for the future, Dr. DeBakey points to the invention which garnered him NASA’s Commercial Invention of The Year Award, the DeBakey Ventricular Assist Device. Based in part on space shuttle technology, it’s a mechanical device that gives failing hearts an extra boost, providing many of those with terminal heart disease a better chance of surviving until a heart donor can be found. “The MicroMed DeBakey Ventricular Assist Device (VAD) has been used successfully in more than 300 patients to date and (a smaller version) is also being used successfully in children because of its miniaturization. It is now under study for destination therapy, that is, for permanent implantation.” But advancements like this are no accident. According to the doctor, “Prevention and effective treatment depend on discovering the causes of disease, and causes are almost always uncovered by medical research. I hope, therefore, that the public will become educated to this fact and will support medical research funded by the private sector and government.”

So much work and time spent contributing to the field of medicine makes you wonder just what keeps the doctor going. Dr. DeBakey explains, "Seeing patients come to the hospital suffering or disabled, and then seeing them leave without pain and able to resume a normal life is gratifying to every physician. I also enjoy the intellectual process of medical research: recognizing a problem, designing experiments to study it and developing a solution to the problem, whether in the form of a new surgical procedure, improved surgical instrument or new therapeutic device… the exhilaration of a successful surgical outcome or research discovery."

There's little doubt the doctor had a treasury of professional accomplishments to look back on and enjoy. But the memories he seemed to cherish most are those with faces. "Excellent teachers and mentors, the small and large pleasures afforded by family, friends and colleagues; the opportunities to travel to all corners of the world and to meet fascinating people in all walks of life."

Perhaps it’s been the students that gave the doctor a global outlook, perhaps his Lebanese heritage. What seems certain is that Dr. DeBakey embraced a set of values that he applied to his profession, both locally and globally. Whether helping foreign or domestic governments in crafting health programs or guiding a heart surgeon through a particularly complex surgical procedure or consulting with students at his beloved Baylor College, Dr. DeBakey had a clear idea of what the world needs.

“Everyone should have an opportunity for education and should have the freedom to pursue individual potentials.”

Individual potential. Not just words from a man like Michael DeBakey, but a way of life – a long and busy and important life spent striving for excellence, devoting himself to service and holding fast to the ideals laid out for him by his mother and father nearly 100 years ago. More than the awards and the acclaim and the success put together, these are the reasons I would most like to reach out to the parents of this great man and say, “Raheehja DeBakey and Shaker Morris, your son is my hero.”

Page created on 8/27/2008 8:16:34 AM

Last edited 8/4/2024 11:11:56 AM