|

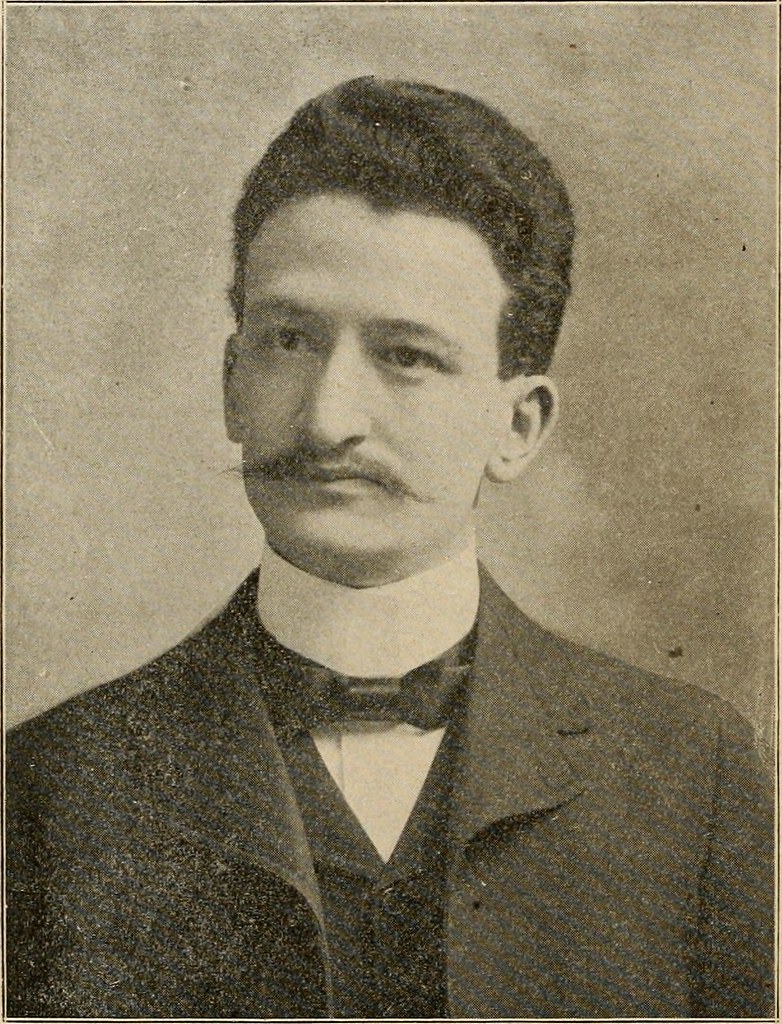

| Bernard Fantus Smithsonian Institution / Public domain via Wikimedia |

Bernard Fantus, the Father of the American Blood Bank, was born in Budapest, Austria-Hungary, on September 1, 1874. The eldest of five sons of David and Ida (Gentili) Fantus, Bernard was destined to work in the medical field from an early age. His father, who had not had the opportunity to pursue his own dream to become a physician, would frequently say to his eldest, "You're going to be a doctor" to which young Bernard would often add with confidence, "I'll be a professor." Bernard completed his pre-medicine studies at the Real-Gymnasium in Vienna before he and his family moved to the United States in 1889. Bernard was seventeen. In 1892, the family moved to Chicago, Illinois. During his early years in the United States, Bernard worked as a drugstore pharmacy assistant for income. Work at the pharmacy was fascinating to Bernard and he acquired knowledge and skills there that he would apply to his work throughout his life.

In the meantime, his father had not given up on his plan for his bright son. David Fantus offered to barter his print work to the University of Illinois in exchange for his son's admission and first year tuition to the College of Physicians and Surgeons in Chicago. Happily, the university took a chance on Bernard Fantus. Bernard's subsequent work at the college was so outstanding that he was able to earn enough scholarships to fund his remaining years and obtained his degree in 1899.

After graduation, Dr. Bernard Fantus fulfilled his internship at Cook County Hospital and then continued to push the limits of his knowledge. His academic work was impressive; he studied pharmacology in Strasbourg and Berlin and received a Master of Science degree at the University of Michigan. His medical expertise also was notable, involving his staff responsibilities in Cook County Hospital, his teaching, research and writing, his work in pharmacology, and his own private practice. Each one of these areas would require pages of tribute for his accomplishments!

The turn of the century was an historic time in the organization of medical practice and Dr. Fantus; wide abilities, avid curiosity, drive to understand and passion to serve, combined with happy consequence for us all in a major way.

|

| Bernard Fantus College of Physicians and Surgeons of Chicago / Public domain via Flickr |

To understand how far medicine progressed during Dr. Fantus' lifetime, one need only view photographs and read personal accounts from that era of his childhood and young adulthood. Imagine someone in a major city like Chicago in the late 1880's. Say they had just been in a terrible traffic accident and had sustained major injuries. After enduring a bumpy ride to the hospital in the back of an open patrol wagon-ambulance, and having lost a good bit of blood, the patient's relatives and friends would be fetched in the hope that several of them might be able to provide enough blood for the patient to survive long enough for the needed surgeries. These "excitable relations," as they were called by hospital staff, often filled the hospitals of this time. If the patient was from out of town, or homeless, or had no relatives, "donors" would be called for. As Dr. Fantus related, "The response sometimes would be a horde of noisy, gesticulating foreigners" from whom "a little blood had to be drawn from half a dozen or even more" to find a match.

It was often hit or miss as to whether the doctors would be able to find the correct blood type match for the patient in time - not to mention the time required to perform the Wasserman reaction test for syphilis or malaria. "The patient not infrequently expired before the blood suitable for transfusion was obtainable." (Dr. Fantus) Even if they were fortunate enough to have several matches, their assisting relatives or friends (or donors) might have eaten a meal just recently (changing the chemistry of the blood), or have had an undiagnosed communicable disease, either of which might dramatically lessen the patient's chances for recovery. A safe and ready blood supply would be indispensable for survival, would it not?

|

| Fantus and daughter University of Chicago Library / CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia |

Fortunately, the technique of conducting blood transfusions was speedily improving at this time; surgical equipment for connecting veins and arteries had advanced and knowledge of these techniques was being disseminated quickly throughout the U.S. and Europe. It was common knowledge that sterilization was vital in each and every step of the process. Richard Lewisohn and others had discovered that a small amount of sodium citrate added to a flask would prevent the clotting of blood. Thanks to the theory of Alexis Carrel and the subsequent work of Oswald Robertson, refrigeration of blood had been successful in the trenches of World War I. Karl Landsteiner discovered the answer to the mystery of why so many earlier transfusions had failed: it had not been known that each human being had one of four blood types and several types were incompatible!

Dr. Fantus' interest in blood transfusion heightened after reading about the breakthrough work of Russian scientist, S.S. Yudin. Yudin had successfully saved and used cadaver blood for transfusions after discovering the timing of coagulation. After considering this resource, Dr. Fantus realized that only the blood from healthy, living donors would be acceptable to the patients of his community. He fervently dedicated himself to the goal of establishing a steady and safe supply of blood for his patients at Cook County Hospital.

We may not think about it today, but the concept of a "blood bank" was practically unknown until Dr. Fantus started one. He invented the name itself, inspired by the idea of the community making deposits of blood "on account" to be available to any who needed it.

But first, there were problems to solve...

"Cook County Hospital had become a "trial and error" laboratory where physicians observed observed the advantages of transfusions, but also observed reactions which occurred in recipients who had received carefully preserved blood. Dr. Fantus was thus able to correlate all the phenomena involved in transfusion. Not only did he initiate the use of preserved human blood but, with the cooperation of the medical staff, observed both good and bad reactions, searched for the causes of untoward after effects, corrected technique, taught his methods to innumerable physicians, and gave blood banking a foundation for future achievements."

To say that Dr. Fantus and his staff satisfactorily solved all of these problems would be true but that would sound too easy! His staff's painstaking care, rigorous observation and precise implementation, taken over time, made the program the permanent success that it is today. Modern surgery worldwide would not exist without it.

Dr. Fantus opened his blood bank at Cook County Hospital on March 15, 1937. Before the bank, Cook County physicians did about 40 transfusions a month. Transfusions increased in the first three months to 400; they shot up to 700 the following year.

Dr. Fantus not only conquered the myriad challenges of creating the world's first blood bank; in July 10, 1937, in the Journal of the American Medical Association, he published in precise detail the principles of organizing a blood bank so that hospitals worldwide would have a master plan of their own to follow. It wasn't a moment too soon. In 1940, when the German "blitz" struck London, blood banks there were already up and working. It is no wonder that JAMA considers Dr. Fantus' article to have been one of the most important they have ever published. It literally saved thousands of lives and paved the way for procedures such as the open-heart surgery and bone marrow transplants that we count on today.

The young Bernard, who had always wanted to be a doctor and professor, had grown into someone not only respected but also very beloved by his community. All who knew him marveled at his wisdom, his dedication and his intelligent kindness. Many of his nurses even referred to him as the "Christ-like Dr. Fantus."

As a teacher, he inspired his students to selfless dedication. As a writer, he encouraged his fellow scientists and physicians to share all they had learned so that their valuable experiences would not be lost. As a pharmacist, he helped to standardize the field of drugs: he made available the first "Candy Medication" for children in order to "rob childhood of one of its terrors, namely, nasty medicine." As a crusader for public health, he wrote numerous articles on the dangers of quack medicine and was an effective whistle blower against popular but deadly nostrums - as well as against the newspapers that made money from their advertisements. As an advocate of the poor, he was alert to any procedures and methods that would assuage their suffering and improve their health. As an administrator of the hospital, he strengthened and expanded it in ways that all have appreciated ever since.

In 1939, Dr. Fantus suffered a heart attack. Knowing that his time was short, he concentrated his efforts on making himself available so that others could carry on his work as well as any of the projects that required his assistance. He even kept a careful account of his illness so that he might add to the knowledge of heart ailments. He died peacefully a year later, at the age of sixty-six, on April 14, 1940. His wife, Emily Senn Fantus, a nurse who throughout their marriage had assisted him in his dedication to serve, and the couple's only child, Ruth, survived him.

About Dr. Bernard Fantus, his niece, Muriel Fulton said it best: "He had this deep conviction that a scientist was to take no credit for his successful work. He put all his time, attention and interest in helping needy people. Can you imagine the millions and millions of people who are walking this Earth today who would not be here if it weren't for the blood bank?"

Page created on 1/5/2015 3:38:08 PM

Last edited 8/4/2024 11:06:40 AM

Candy Medication by Dr. Bernard Fantus (published in 1914) described formula for simple sugar flavoring that any pharmacist could use, including tolu coating to disguise unpleasant flavor (used in cough lozenges even today)

Lowrie, Reed. "Dr. Bernard Fantus: Father of the Blood Bank."(Special Collections Research Center, The University of Chicago)

Mullen, William. "Remembering a simple but profound idea" Chicago Tribune, January 11, 2005.

Norwood, Terrance S., "Cook County Hospital Blood Bank: First Blood Bank in the U.S.A." Cook County Hospital Archives, March 19, 1982.

Reagan, Ronald, The White House. "Washington on the anniversary of blood banking in the United States," June 29, 1987.

Telishi, M., "Evolution of Cook County Hospital Blood Bank" Cook County Hospital Blood Bank, Chicago, Illinois, January 7, 1974.

Wilson, Edwin H., Minister, Third Unitarian Church of Chicago, "A Life of Kindness Guided by Intelligence" Funeral Address for Dr. Bernard Fantus.