|

| His Organization (http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_qMRiA9tNGUE/SarzUQzKDaI/AAAAAAAABP0/4pwtFTyGsBs/s320/cesar.jpg ()) |

In the middle of a desolate lettuce-field, a lonely family works with aches in their ankles and blisters on their hands. One of their children wields a small hoe, the tool that caused his parents to suffer chronic back pain. They choke on the pesticide-laden air from foggy sunrises to frigid sunsets. Their work barely pays them livable wages while giving harsh living conditions, such as no clean bathrooms. This was a normal farm-worker, or migrant-farmer, family in the 1930's. On those fields, one little child worked, too, and his name was Cesar Chavez; he would grow up to help the plight of these people. On March 31, 1927, Cesar Chavez was born in Arizona to a Mexican-American family, and he grew up in his family's property until his family lost it in a shady deal ("Cesar Chavez." Cesar Chavez (Biography Today)). As a result, Chavez toiled up and down the California fields with his family as a migrant. When he became an adult, he lived as a social worker around San Jose in the 1950's and 60's (Rose). Chavez left this work to build a one-of-a-kind union all over the state to help the people that he once was. His union would lead enormous strikes and effective boycotts, such as the large Delano strike from 1965 to 1970 ("Cesar Chavez." Dictionary of Hispanic Biography.), until the voices of the farm-workers fell on the public. For those people, these actions led to more labor and human rights, an idea thought to be impossible decades earlier. He worked with his union all the way to his death in Arizona on April 23, 1993 (Streissguth). When threats and violence came toward him for his cause, Chavez never deterred as long as the cause would continue. Additionally, he only ended any of his or his organization's actions when their adversaries allowed them to achieve productive outcomes. From the beginning to his death, he would advocate on those who suffered in the fields so to improve their well-being. Through his courage against pressures and threats, his perseverance in the face of heavy obstacles, and his selflessness for the rights of migrants, Cesar Chavez exemplifies the traits that make him a hero for everyone to be inspired by in their lives.

|

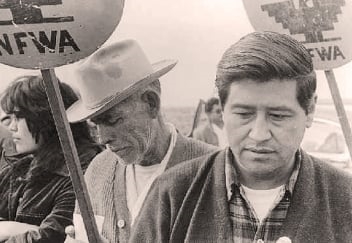

| A Striking Chavez (http://www.emersonkent.com/images/cesar_chavez_nfwa.jpg (Oscar Castillo)) |

Chavez's courage shined when he fought against outside pressures and intimidation. During the Delano grape strike, people striking with Chavez criticized his nonviolence because of anger from enemy violence, seen here: "Frustrated with the growers' brutal opposition, some men were talking about taking up arms. Their leader was dismayed. 'I am convinced,' he told them in a written statement at the conclusion of the fast, 'that the truest act of courage, the strongest act of manliness, is to sacrifice ourselves for others in a totally nonviolent struggle for justice'" (Streissguth). On this disapproval, Chavez declared publicly, and his statement attacked the disgruntled for their ideas that may endanger the movement he started. Then again, this outspokenness set him as target for those disgruntled to try to defame or harm him. If those people were as dedicated as Chavez was but did not have his nonviolent stance, they could have taken arms against him, seeing him as an obstacle in his own cause. Furthermore, even when his enemies fought his movement with violence, he stood his stance on nonviolence. He knew the harm that may come towards his people, but also knew that nonviolence could speak a bigger voice with enough public support. However, his enemies could have exploited the situation and have a decisive campaign to eradicate the opposition, only caring for profits; in reality, they did not do such action, and the movement kept going. Later in Chavez's life and the movement, major companies started to sign contracts with his union to keep themselves from damages and lost profits. However, boycotts kept going due to holdouts while other unions vied for contracts that Chavez's union had won: "After the UFWOC called for a boycott of the prominently labeled bananas, United Brands decided to negotiate with Chavez and not the Teamsters. Still determined to keep their contracts, the Teamsters fought back with threats and violence against the UFWOC. In October, the Bud Antle Company, a lettuce grower that had an agreement with the Teamsters, won a court injunction against the UFWOC, and Chavez spent two weeks in jail" (Streissguth). When the Teamsters used violence and vicious threats against Chavez's organization, the UFWOC, Chavez did not back down in negotiating the contracts he fought hard to get. A formidable and powerful force, the Teamsters could have used its entire power to go against the UFWOC. Weaker leaders could have back down from negotiations at this threat of harm, but Chavez refused such action. In addition, arrests would not change Chavez's perspective on his work. He would work to improve the rights of others, even with such threats of violence and arrests. Those threats came true: authorities arrested him, but only because of a dispute with another union. As such, Chavez may have seen this as another obstacle to overcome, and his work would always continue. Throughout his effort, Chavez never backed down from threats that affected his work, whether they are from other groups or his own group. This bravery allowed him to be able to persevere in his work for the inspiring struggle for migrant rights.

|

| A Weakened Chavez (http://museumca.org/picturethis/sites/default/files/imagecache/page/pictures/h97.1.912.jpg ()) |

Chavez endured many obstacles to his work, but his admirable perseverance kept him going. From the beginning, Chavez met various hindrances: "With the $1,200 that comprised his life savings, Chavez then formed the National Farm Workers Association in Delano. Chavez spent several months in the fields of the Imperial and San Joaquin valleys, convincing farm workers to join the union. These were difficult times financially for Chavez, and he was often forced to beg for food from the workers he was trying to organize" ("Cesar Chavez." Dictionary of Hispanic Biography.). He gave all his life-savings into an idea that no one thought could succeed. Consequently, his livelihood now tied with this new organization. At the time, there was no sure way for him to earn money, so Chavez and his family had to suffer a bit financially. Other people may have not given all their money to their ideas, but Chavez did. Even suffering from hunger did not deter him from his cause, and worse, early recruitment into the new association was slow and difficult. Chavez traveled constantly to visit the people he wanted to join his association to advance their labor rights. This brought hardship to him and his family, and he had to go hungry sometimes. Occasionally, he would probably have fruitless days where he would not convince anyone. Nevertheless, Chavez continued to travel in pursuit of his goal, and his work led him all the way to his first large-scale action: the Delano grape strike and boycott. The strike and boycott took much time until growers gave rights: "The strike and boycott continued for five years, but eventually the grape growers acceded to their demands and signed a union contract, increasing the workers' wages, protecting them against pesticides, and guaranteeing their right to representation and collective bargaining. It was the first time in U.S. history that farm workers were protected by a union contract" ("Cesar Chavez." Cesar Chavez (Biography Today)). The strike and boycott lasted years, and in those years, the movement must have had times where people thought the actions produced nothing. The strike could have failed and the boycott could have lost its public support. Even so, Chavez pushed these ideas away and continued advocating these actions, maybe quietly doubting it himself sometimes. Throughout the strike and boycott, the lack of useful dialogue with the growers may have added more anxiety on Chavez on whether his organization's actions could have lasting effect. Even near the strike and boycott's end, he could have been worrying about whether the growers would truly accede to his organization and him. However, the grower signed contracts with the union, and all because the movement never died down. Chavez suffered through a slow beginning and lengthy actions against the oppressors of the migrants. When such situations seemed hopeless, others could have given up, yet Chavez continued against this bleakness. Additionally, all this perseverance was to help the common farm-worker, the oppressed.

|

| Pesticides (http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-ZOFEdkytWb0/TzccB-OcZPI/AAAAAAAAoDA/MoLhizQ9V-0/s320/BE072407.jpg ()) |

Through his life-long work to advance the migrant worker's life, he demonstrated altruism. Chavez battled labor rights for farm-workers and other methods of helping them, starting from his organization's beginning, as seen here: "... Cesar read a proposed plan of action: The new National Farm Workers Association would lobby the governor's office in Sacramento for a $1.50 an hour minimum wage for farmworkers and the right to unemployment insurance. The association would still avoid the term 'union,' but it would advocate for the right to collective bargaining, something bound to raise the ire for growers. Equally ambitious was Chavez's plan to establish a union-run credit union for members, and a hiring hall" (Ferriss 73). Chavez knew that the rights of the migrants would stay unreachable without unions or other backing. Immediately after building the organization, he fought for basic labor rights such as minimum wages and unemployment insurance. At this time, he was not a migrant but a social worker, yet he still fought for those stuck in his previous vocation. Others could have forgotten those harsh times, but Chavez remembered them and made it cause to rally around. In his first union plan, Chavez wanted a credit union to try to lift the common farm-worker out of the poverty that kept them being such people. He also wanted a hiring hall so that farm-workers could find jobs without going to places first, as people once roamed only to find no work. Both were designed to steady the working and living conditions of the people that he once was. He fought for the welfare of the common farm-worker in many topics, and pesticides were part of those fights: "'During the past few years I have been studying the plague of pesticides on our land and our food,' Cesar continued.' The evil is far greater than even I had thought it to be, it threatens to choke out the life of our people and also the life system that supports us all. This solution to this deadly crisis will not be found in the arrogance of the powerful, but in solidarity with the weak and helpless'" ("The Story of Cesar Chavez."). Pesticides helped only the growers as the chemicals allowed them to sell more crops while affecting harming the workers. These chemicals effects must phase-out to help the welfare of these workers, and the person who fought against their use was Cesar Chavez, fighting for pesticide withdrawal and labor rights. Additionally, the regular person would think of pesticides as a necessity to kill bugs and stop their diseases, but Chavez saw firsthand their effects on people. While he may have been fighting for ending its use for the migrants, he also fought against it for everyone else. He knew that the pesticides might transfer to the consumer, possibly causing harm. Chavez spoke specifically about others in the "life system that supports us all" part. Due to his migrant-worker experience, Chavez devoted his life to help their lives and others by advocating for more rights and better living conditions. These migrant workers were ignored by the majority of people, but Chavez worked tirelessly for these oppressed people. He devoted his life for the happiness and living standards of these people.

Cesar Chavez worked endlessly to help the people in the fields, whether suffering adults in broken huts or toiling children in lettuce-fields. His work and actions must have inspired others of all backgrounds to speak out their voices. Chavez acted bravely against oppression and danger that could have seriously harmed him, persevered in times of uncertainty and seemingly endless times, and devoted his life selflessly for the living standards of migrant workers. Cesar Chavez fought for a collection of workers who were hidden from the public, and those same workers were exploited by their employer for their financial status. For there be an actual chance of helpful change, Chavez had to build an organization from practically nothing. In his organization, he never terminated any of his actions whether they took long durations or else viewed as hopeless or uncertain. He waited the situation out until success was achievable, and the goal was at least the same amount of rights as other labor groups. Heroes like him must show compassion to others and devote all of their power to this ideal. Everyone of any heritage can act with compassion towards others and become a hero to be looked up by all.

"Cesar Chavez." Cesar Chavez (Biography Today) (2010): 1. Biography Reference Center. Web. 24 Mar. 2012.

"Cesar Chavez." Dictionary of Hispanic Biography. Gale, 1996. Gale Biography In Context. Web. 25 Mar. 2012.

Ferriss, Susan, and Ricardo Sandoval. The Fight in the Fields: Cesar Chavez and the Farmworkers Movement. Ed. Diana Hembree. San Diego, CA: Harcourt, 1998. Print.

Rose, Margaret. "Cesar Estrada Chavez." American National Biography (2010): 1. Biography Reference Center. Web. 21 Mar. 2012.

Streissguth, Thomas. "8: Cesar Chavez Nonviolent Crusader." Legendary Labor Leaders (1998): 133. Biography Reference Center. Web. 25 Mar. 2012.

"The Story of Cesar Chavez." UFW: The Official Web Page of the United Farm Workers of America. United Farm Workers of America, 2006. Web. 26 Mar. 2012. .

Page created on 4/19/2012 12:00:00 AM

Last edited 1/6/2017 4:44:11 PM