|

| Cameron Sinclair (TED.com) |

Born in London, England in 1973, Cameron Sinclair has long been interested in architecture that serves the humanitarian and cultural needs of its inhabitants. It’s a passion that took root during his training at the University of Westminster and The Bartlett School of Architecture at the University College London and has flourished ever since.

Sinclair has been recognized for his efforts by institutions of higher learning (An honorary doctorate from the University of Westminster in 2008), and organizations like TED, The World Economic Forum and the Design Futures Council but his greatest reward is the work itself. Each year, more than 25,000 people directly benefit from designs that originated from AFH.

|

| Cameron in India after tsunami (Architecture For Humanity) |

It seems every hero is confronted with a moment when they move away from the role of the observer, step forward and take action. For my hero, architect Cameron Sinclair, that moment came in the late 1990s, when he and his partner, Kate Stohr were watching the news. There on the television played the story of the Kosovo war and the resulting displacement of nearly a million people. In the midst of the rubble and the ruination of whole communities, Cameron saw an opportunity for architects to help. “We just said to ourselves, I’ll bet that there’s more than just us who care about these communities and want to use… creativity… to make a difference.”

The two decided to run a competition. The goal was to reach out to the design community and crowd-source ideas for practical, livable structures that could be built in the affected areas. Sinclair remembers the initial response, “Almost every designer and architect I spoke with wanted to get involved in responding to humanitarian issues.” The response was overwhelming. Groundbreaking designs in refugee housing came in from all over the world. From inflatable tents to re-purposed rubble, plans poured in that addressed not just the buildings, but the people; their lives and hopes for the future.

|

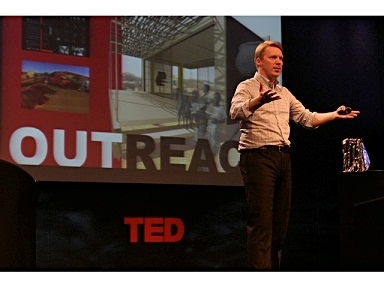

| Cameron, live at TED.org (Architecture For Humanity) |

And so was born Architecture for Humanity, a worldwide network of architects offering their unique creative abilities to humanitarian groups and needy communities who can most benefit from them – not just those who can afford them. “Well thought out and innovative design should not be tied directly to cost,” Sinclair explains, “We have an amazing opportunity to improve the the built environment for everyone.”

“Design like you give a damn” became their motto and a call to action. Architects and product designers embraced the idea by the thousand. And professionals in the field who formerly found themselves designing towel racks, garage doors and soap dispensers suddenly had a conduit through which to channel not just their skills, but their hearts.

Since its birth in 1999, Architecture for Humanity has grown into a community of over 50,000 professionals worldwide.. And as the organization’s “CEO” (Chief Eternal Optimist), Sinclair is responsible for bringing them together.

“One aspect of our business is matchmaking,” explains Cameron, “We’re kind of like the dating service between humanitarian groups and communities and architectural designers.” The results are improving lives in communities across the world. From raised, organic gardens in Oakland, California to The Youth and Women’s Leadership center and Homeless World Cup in Santa Cruz, Brazil; from football fields across Mali to community centers in hurricane ravaged India and Sri Lanka.

For many Architectural firms, a strong portfolio of work can bring clients in search of their services. In the case of Architecture for Humanity, the firm seeks out clients that most need their help.

|

| Homeless World Cup Stadium Santa Cruz, Brazil (Architecture For Humanity) |

An example of one such client was a small village in Southeastern India. The community had been devastated by the tsunami in 2004. Many homes had been washed away, leaving their village strewn with rubble and their future uncertain. Enter Architecture for Humanity and a young woman determined to make a difference.

Purnima McCutcheon is an American trained architect who was working for a commercial company, doing very large projects, when she picked up and travelled to India to help. “It’s always been my aspiration to at some point work with the community and do something that was more personally meaningful.” Though established in her career, Purnima wanted to help. This time, the project would be measured less in size and cost and more in the lives of the people for whom it would be built.

|

| Architect Purnima McCutcheon (Architecture For Humanity) |

After interviewing villagers and compiling a list of needs, Purnima designed a town hall that would go a long way toward fulfilling them. After some modifications to further address the needs and concerns of the villagers, Purnima arrived at the final design. “It is hard,” she explained, “but you just have to listen … otherwise it becomes your building more than theirs.”

What makes these projects so worthwhile for all involved are the relationships that are formed between designers and the communities – the individuals – whose lives they enrich.

Matchmaking isn’t a line you’ll find on many architects’ resumes, but for Cameron Sinclair, bringing his colleagues together with the people who can most benefit from their skills is a job he wouldn’t trade for anything. Because when it clicks and needs are met, societal bonds strengthened and cultural lives enriched, it’s a match made in heaven.

MH: WHO IS YOUR HERO AND WHY?

CS: “I think my personal hero would be my grandmother, who I lived with for about 6 years in my teens... she worked until she was well into her mid-90s, she had three jobs - not really so much for the income but because she loved what she did. She was an artist and costumer and did set design for opera and ballet from the time she was 16. What I like most about her - what had the most impact on me personally, was that she was the first role model I had who took art seriously as a career. She believed in the impact of the arts on society - that creativity could spark change both inwardly and outwardly - that creativity has the power to change everything from the individuals themselves to world issues. She also was very pragmatic at the same time - a realist - which was good for me because as a personality, I’m completely optimistic and always looking for opportunity even in grim circumstances. She gave me a sense of grounding - so when I’ve approached problems, I haven’t looked at them with a utopian idealism but in a more grounded way, with a broader perspective, looking at context and how that can happen. I grew up not thinking that I would have to settle because I would have to grow up and have a career - she lived her life like the things she loved were her career and that’s exactly how I live my life."

MH: WHAT DID YOU LEARN FROM HER?

CS: "Probably the most important thing I learned from her was - in her study, she had literally hundreds and hundreds of pieces of artwork she’d produced... folder after folder... and none of it was signed. And I said to her, “You’re a great artist, people love your work why don’t you sign your work?” Her response was, “Does it matter?” She knew she’d done that work and the viewer knew. Signing it... there was no reason. If you look at the work of Architecture For Humanity - it’s not about the creator it’s about the recipient. There is no ego in our work. When there is ego in the work that Architecture for Humanity does, it ceases to have impact. We pride ourselves in not putting any signage anywere on our buildings. We celebrate the building, not the designer.

MH: WHAT ROLE DOES MENTORING AND MENTORS PLAY IN YOUR LIFE AND WORK?

CS: "Mentoring is highly important - we have a lot of young professionals that come in and they’re conflicted - do they want to become a celebrity architect, designing skyscrapers and the like or do they want to participate... do community-led, grassroots architectural projects? Mentors show guidance and relevance - when architects start, they think more about the design but then you often don’t get perspective until a project’s complete and you understand the eco-system of impact. Having mentors that can show you your role in that - in the impact your design has on the community - is really important."

MH: WHAT HAS ARCHITECTURE FOR HUMANITY TAUGHT YOU ABOUT PEOPLE?

CS: "That there’s incredible resilience in communities affected by natural disaster or systemic poverty... and we are not there to tell them what to do. When you put your trust in a community and marry that with technical expertise, real miracles can happen and I really love being a part of that."

MH: WHAT WOULD YOU SAY TO YOUNG PEOPLE TODAY?

CS: "I came up with this idea in high school - it took me until I was 22 to be brave enough to go for it. Don’t settle - if you’re young you have an incredible opportunity - you have a carefree life - now is the time you can take the ultimate risks and if you direct them toward real tangible goals you can really do great things.

And if there’s a young student out there who’s got a really great idea - give us a call."

Page created on 11/5/2011 12:00:00 AM

Last edited 11/13/2019 6:00:12 PM