|

| My brother Trey holding two babies (personal photo collection) |

When I was in high school I attended a very prestigious preparatory boarding school in New Hampshire. My parents are American diplomats and at the time were living in Kampala, Uganda on the East Coast of sub-Saharan Africa. My parents’ work in Third World nations had provided me with a firm understanding of the suffering in the world, and with an innate obligation to alleviate it. But after two years of New England living, surrounded by Kate Spade handbags and Yale sweatshirts, my focus drifted from wanting to better the places I called home in Africa. I began to let my dream of serving in the military slip away, maybe for Tulane or Georgetown, somewhere warm and fun, somewhere that would help me make money later in life. I began to resent going home to Kampala, wishing my family lived closer to New Hampshire, wishing the roads were paved, wishing the earth was brown and not shoe-staining red.

|

| Nathaniel with a baby and a visitor (personal photo collection) |

During Spring Break my junior year, I went home to Uganda. After lounging around home for a week, my parents decided that my older brother, who attended school with me, and I needed to do something with ourselves. We packed our bags and climbed into our Japanese SUV and drove south to Masaka. The village was like most African villages: clay houses with tin roofs, ancient Coca Cola signs plastered to ancient concrete buildings, women with colorful dresses carrying water and fruit on their heads and babies on their backs, small children waving. We arrived at a small gate with a sign reading “Aidchild” in blue letters on a white background. A tall white man with glasses and blonde hair gelled into spikes walked out of the main building, small black children clinging to his arms and legs. He introduced himself as Nathaniel and then introduced the children, still hanging on him like ornaments on a Christmas tree. My father opened the back of our car and began to take out old toys we had brought for them. The children momentarily abandoned Nathaniel and rushed my dad. They scoured the boxes, looking at everything, even some of the older, dirtier, in some cases broken toys, as though they were treasure. Again, I was reminded of Christmas morning, the excitement and utter joy was tangible in the children. Once they each had something in hand, they returned to Nathaniel’s side, showing him their prizes. He smiled down at them, clearly pleased by their joy.

|

| Giving Miriam a piggyback ride (personal photo collection) |

After my parents drove away, my brother and I toured the grounds. Nathaniel explained to us that Aidchild was home to about twenty Ugandan orphans, all infected with HIV or AIDS. Their parents had died and their families were either unable to care for them or dead as well. Fifty percent of the Ugandan population is under the age of fifteen and of that group around 20% are infected with HIV. Most of the kids at Aidchild had arrived there on the brink of death. Nathaniel told us about Toby, a young girl who had been dropped off a few months ago, covered in open sores. The medical staff at Aidchild covered her in an antibiotic ointment that had a blue tint. For days the staff referred to her as a smurf, running around with the other children covered in blue. When I saw Toby, her face and body were badly scarred, but her eyes were bright and her smile was infectious. There was Isaac, a gregarious little boy with huge eyes and bulbous fingertips. I often wondered if it was a birth defect, but it complemented his sense of humor. When he tried to explain something to me in Luganda, the Ugandan language, he would wave his oddly shaped hands and widen his enormous eyes, and I could not help but erupt in laughter which, in turn, would throw Isaac into a fit of hysterics too. Isaac and I spent a lot of time together that week, speaking to each other in our own languages, neither one of us understanding a word the other spoke. But every time we laughed or exchanged a grin, hugged or squeezed a hand, in those moments I understood everything I needed to know. The children were so happy and fun, I had to remind myself that they had AIDS. After the first day, I stopped reminding myself that the children were ill. They were just children and, thanks to Nathaniel, a virus would never again define them.

|

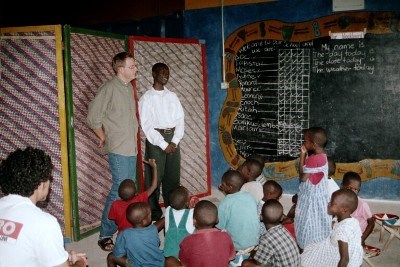

| Nathaniel at Aidchild school (personal photo collection) |

The children call Nathaniel “daddy”. They hug him and kiss him like he is their actual father, and he, too, embraces them as his children. He sings to them and reads them stories at night, chastises them when they are naughty, but then embraces them immediately after, for life is too short to stay upset, and these children’s lives will be shorter than most. One child at Aidchild was very ill that week I was there. He had gone entirely deaf and was very weak. The medical staff had him on an IV and even though he was in horrible pain, he never cried. When Nathaniel brought my brother and me to see the boy, his eyes struck me. They were the eyes of an old man, tired and weary, ready to surrender. Nathaniel gently picked him up off the bed and cradled him in his arms. The boy showed no sign of caring, no indication that he even knew he was being held. But Nathaniel held him anyway, cooing and whispering words I could not hear into his deaf ears. Later that day I asked Nathaniel how the boy was doing and he told me that he was not sure how much longer he would survive. The look on Nathaniel’s face at that moment was heartbreaking. I had never lost anyone I loved, but I recognized the emotions of loss and anger in Nathaniel. Everyday he cared for children, children he was guaranteed to lose, children he loved and who loved him, children the rest of the world had forgotten or were too busy to care for.

|

| The flags (personal photo collection) |

On my last day at Aidchild I asked Nathaniel about the flags that stood near the gate. There were five or six flags of varying colors with single letters in the middle, each on their own pole. Nathaniel gave me a sad smile and told me that each flag represented a child that had died at Aidchild. He explained that after a child passed away, the other children would sit with Nathaniel and talk about their lost friend and choose a color for the flag. The whole group would go out to the flag pole and raise the flag to half mast. The flag would remain at half mast until someone who knew the child (a sibling, family member, fellow villager) would come to Masaka and raise the flag to the top. Nathaniel said that this way the children were never forgotten.

As I drove away from Aidchild, covered in the dried saliva of wet kisses from the children, I looked back on Aidchild. The flags waved to me from the hill as though they were the children, past, present and future, wishing me well and sending me home with the greatest gift I have ever received. That night, I prayed for the first time in a long time. I prayed that the children would be safe and healthy, and to take them from this life as gently as Nathaniel cared for them in it.

Nathaniel is my hero for a multitude of reasons. The sacrifice he has made and continues to make to give hope to those in desperate need is unprecedented. He gives each child a piece of his heart, a piece he loses forever, stolen away by an unworthy virus. He lets people like me, so overly concerned with their own lives, come to his haven in the middle of Africa. I know Nathaniel built Aidchild to save Ugandan orphans with HIV/AIDS, but those are not the only lives he saves. Everyday, the people who work and visit Aidchild cannot help but be touched by his mission and the way it manifests itself in the children.

Today my sister is working at Aidchild and my mother keeps in close contact with Nathaniel. My boyfriend donated to Aidchild in the fall and all of my friends have seen the pictures and read Nathaniel’s journal entries on Aidchild’s website (www.aidchild.org). To most people, it probably comes off as though I am trying to guilt them into donating or caring about yet another one of my causes. But that is never my intent. My hope is that maybe I can give a piece of Nathaniel to them. To be in the presence of such compassion, your soul is forever transformed. Nathaniel reminded me that my own life is worthless if not used in the service of others.

I did not follow Nathaniel’s path to Africa, but carved my own, which led me to the United States Coast Guard Academy. I sometimes wonder if the work I do when I graduate will parallel Nathaniel’s. I wonder if I will be changing lives as dramatically as he has, if I will be saving lives like he has. There are days when I am ashamed and angry, wishing I could do more to help than sitting in a classroom waiting for my turn to serve. On those days I usually go to the Aidchild website and read what Nathaniel has written about his children and look at the photos of the children I met at Aidchild, years older and years happier. One picture always strikes me and brings tears to my eyes. It is a photo of a man raising a green flag with the sun shining down on him. There are more flags in the photo than there were a few years ago, more children have died. But the flags still wave in the wind, the same way they waved at me when I left Aidchild four years ago. Those flags, those children, motivate me to continue to serve in the Coast Guard, to keep sacrificing for people I do not even know. I think of Nathaniel and Aidchild and the hope it provides to Isaac and Toby and Kasumba and all the other children living there, spending their lives loved and loving. Those children will never be a statistic; they will never be another African with AIDS. Nathaniel is my hero because he creates hope in its purest form.

Page created on 7/17/2006 2:23:04 PM

Last edited 6/30/2020 2:17:11 AM