About Felton Earles

On April 5, 1968, neurophysiologist Dr. Felton Earls emerged from a soundproof room in an underground laboratory at the University of Wisconsin, where he had spent the last 36 hours mapping the responses of a cat’s brain to high- and low-frequency sounds. What he found was a campus in uproar, and a totally changed world; Dr. Martin Luther King had been assassinated.At that moment, Earls decided he could not in good conscience spend his career shut off in the cloister of the academic laboratory. He rededicated himself immediately to what he calls society's best hope: our children, and the communities that nurture them. He switched professional gears to gain degrees as a pediatrician, a child psychiatrist, and a professor of human behavior and development at the Harvard School of Public Health.

Earles has become a social scientist in the most literal sense of the term--a doctor who treats communities. According to a January 6, 2004 article in the New York Times called "On Crime as Science (One Neighbor at a Time)," his groundbreaking field research is credited with debunking the "broken windows" theory of crime and is turning the field of criminology on its head. His research reveals a startling finding: The most important determinant with respect to crime rates is not race, IQ, family, or individual temperament, but the willingness of neighbors to act, when needed, for one another's benefit, particularly for the benefit of one another's children.

The policy implications of his work are far-reaching. In the words of a former director for the National Institute of Justice, this finding is "far and away the most important research insight in the last decade."

Earls is currently collaborating with his wife of 32 years, the neurophysiologist Mary Carlson, M.D., on a project to promote the well-being of the devastating number of children who have been orphaned by AIDS in Tanzania.

|

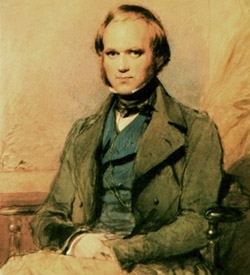

My hero is Charles Darwin, the nineteenth-century naturalist. This long-dead white Englishman may seem a strange choice: after all, Martin Luther King, Jr., changed the course of my life. And as a child, I desperately wanted to be a musician, so why not one of the many jazz artists who continue to enrich and enliven my life, like Louis Armstrong (my homeboy from New Orleans), Miles Davis, Keith Jarrett, or John Coltrane? I could stretch it and claim one of these men as well, but I don’t need two heroes; I need only one.

No one has had as great an influence on me--as a scientist, or a man--as Charles Darwin. His scientific rigor, intellectual brilliance, and the innovative nature of his methods have influenced, challenged, and comforted me countless times. So many aspects of his life and work directly touch my own that I consider myself to be permanently in his grasp.

I was probably about sixteen or seventeen years old when I first read Voyage of the Beagle, and I devoured every page with a sense of astonishment. How could anyone compile such detailed notes and weigh the evidence stemming from so many ideas all at the same time?

As impressed as I was by the comprehensiveness, the thing that had the most profound effect on me was Darwin's method. Up until that point, I had thought of science as something that took place in a laboratory: you harvested specimens from their natural environment, brought them back to an artificial space, and controlled everything about them as you observed them.

What Darwin did in the South Seas was the exact opposite. He was, first and foremost, an ecologist, dedicated to understanding things in their place. The world itself, in its natural form, was his laboratory, and his work was a vital and dynamic part of the natural world--not apart from it. The idea that you could do fundamentally important science outside of the managed environment of the laboratory was revolutionary to me, and it had a direct impact on the methods I chose to adopt in my own work and continue to use today.

As I was to learn firsthand, it's not always easy to work without the conventional apparatus of a laboratory. You’re viewed as an outsider, and there still is a pervasive idea that research done this way is somehow less scientific or rigorous than work done in the lab. It has comforted me, over the years, to know that this method resulted in Darwin's theory of evolution, one of the single most significant achievements in science. But I have taken another cue from Darwin, who answered critics of his method by bringing the rigor of the laboratory to the field.

To my mind, he is the consummate scientist, the exemplary standard, and he sets the bar for me every time I design an experiment or an instrument to analyze data. Darwin painstakingly collected his own data, analyzed it with attention to an infinite number of details, and then patiently interpreted his findings in the most elegant and groundbreaking way possible. The controversy about his work always strikes me as ironic, because he was such a conservative scientist. He was so meticulous that his methods would stand up to a National Institutes of Health review board today.

Another, often overlooked, aspect of Darwin's work was his social sensitivity. He was a devoutly religious person; in fact, it was while studying to be a cleric that he seized an opportunity to travel the South Seas as naturalist on board the Beagle. And although he was initially reluctant to bring humans into his grand theory--The Origin of the Species is pretty much exclusively about the lower orders of animal life--the miserable social conditions he witnessed on his voyages do not escape his notice. For example, in the final pages of Voyage of the Beagle, he criticizes the institution of slavery: "On the 19th of August we finally left the shores of Brazil. I thank God, I shall never again visit a slave-country. To this day, if I hear a distant scream, it recalls with painful vividness my feelings, when passing a house near, I heard the pitiable moans, and could not but suspect that some poor slave was being tormented, yet knew that I was as powerless as a child to remonstrate."

This sensitivity to the human condition was always at the root of the way Darwin pondered life on Earth, and that concern is boldly outlined in the later two books he wrote on human development. In those books, he links the biology of life with the morality of man.

This connection captured my consciousness totally, and eventually formed the basis for one of the biggest ethical decisions I have made over the course of my life: the decision to become a conscientious objector when I was drafted to fight in the war in Vietnam.

|

| Charles Darwin |

I had already been persuaded by Martin Luther King, Jr., that nonviolence was a stronger force than retaliation, a hard lesson to learn. But as important as Dr. King's moral leadership and spirit were to me, it was Darwin, ultimately, who helped me to focus my thoughts about war.

Darwin believed that humans were part of the natural order, and his writing instilled in me a terrific respect for our place in that order. Furthermore, he proposed the idea that humans are a fundamentally social species; we have evolved in a way to make us respond to others in a sympathetic way. He believed that we are designed to recognize and protest injustice, even as very young children, because a social species survives best when its members take care of one another. This conclusion moved me deeply, and I believed that war was the most horrible contradiction of those principles imaginable. It was a contradiction in which I could not, and would not, participate.

Darwin--the man and his methods--continues to inspire and guide me today. One thing in particular gives me hope for my own future. Although Darwin took long trips away from home, he also spent long periods of time in seclusion with his family at Down House, his home and garden in the south of England, assimilating what he'd learned. Once he had all the data he needed, he turned away from the scrutiny of his peers to master his understanding of living things.

The feeling of his separateness from the academy was the thing that stood out for me when I visited his house thirty years ago--and at this stage in my life, it is the part of his method I most wish to emulate. I admire the fact that he used his aloofness (whether the result of an actual illness, or hypochondriasis, the diagnosis that the psychiatrist in me finds most satisfying) to create a space to reflect.

I am a social scientist and a child psychiatrist, with interest in violence, morality, democracy, and global justice--interests that cannot be contained by the narrow confines of institutional life. I want to embark upon a free and creative exploration of the world in which I live and which I care deeply about . But as an institutionalized scientist my time is spent in attending committees; in organizing and supervising a team of research assistants, statisticians, and administrators to execute field work; in data analysis and publication. I spend far too much of my time teaching, writing grants, and pondering budgets, rather than thinking and writing.

I have been on a voyage for much of my life, one that has taken me all over the world in search of ways to enhance the well-being of children. Like my hero, I still aspire to spend some years putting my ideas, insights, and small discoveries in order. In desperate moments I wonder if I should mimic Darwin and feign sickness--or contract malaria on my next trip to Africa! But heroes are not to be imitated; they are to be admired.

In this way (as in countless others over the last fifty years), Darwin’s example extends to me a beacon of hope and optimism that I might also have a few years to reflect upon what I have learned.

Page created on 2/7/2010 12:00:00 AM

Last edited 8/28/2018 2:08:17 AM

Copyright 2005 by The MY HERO Project

MY HERO thanks Felton Earles for contributing this essay to My Hero: Extraordinary People on the Heroes Who Inspire Them.

Thanks to Free Press for reprint rights of the above material.