|

| ( ()) |

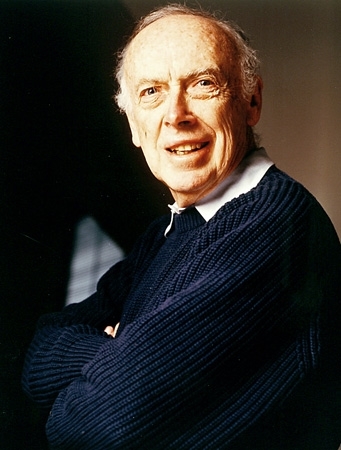

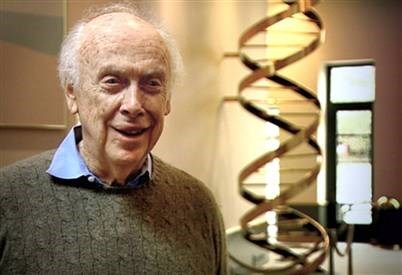

James Dewey Watson was one of the original kids on the popular 1940's radio show, Quiz Kids ("James D. Watson"). However, he is better known as co-founder of DNA's helical structure and sharing the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine with Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins. Watson was born and raised in Chicago, Illinois. He attended the University of Chicago at the age of fifteen where he studied ornithology on a tuition scholarship. After graduating, he went to study at Indiana University under S.E Luria, where he changed his focus to nucleic acids. Through Luria's connections, he met his best friend and partner, Francis Crick, and colleagues in King's College, Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin. Together, the team made their earth shattering discovery. His life before and after this discovery are intriguing tales of inspiration as he continues to utilize his brilliance. James Dewey Watson's open-mindedness, humble optimism and passion to educate others make him a hero.

|

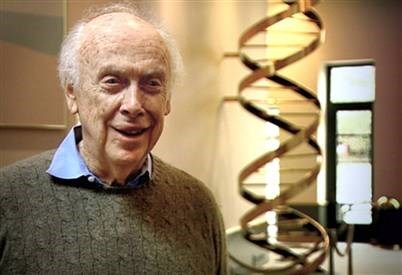

| (scienceblog.com) |

Watson is a very open-minded man, appreciating people for themselves even if their beliefs clashed with his and was not too proud to turn down help from others. Science is often believed to be the enemy of religion, and Watson was asked if he looked down on religious folk: "I have many highly religious friends, and they're never going to think the way I do, and I think I want to let them go on the way they are, and they're letting me go on the way I want to...And they're more satisfied with religious explanations. And my feeling is that if that's what satisfies them - I certainly want to, you know, encourage them to feel, you know, to improve their lives." ("James Watson"). Despite the aforementioned stereotype, Watson felt no need to force his beliefs onto those who were already content with theirs. He accepts that there are other opinions that may conflict with his own, but if they do not affect him, he should not have an issue with it. Watson also understands that sometimes one must rely on others, even those people he might have considered enemies: "But neither Watson nor Crick is highly skilled in crystallography, and they must turn to the experts at rival King's College in London for help in getting pictures of the molecule" ("The Double Helix"). Some are too proud and adamant in not asking others for help. This is not the case with Watson; he realized that the materials they needed were in the possession of their competitor, King's College, and readily requested their assistance. His priorities surpassed his pride, and the decision introduced him to two people who would be crucial to his life-changing breakthrough. Another element that would be crucial to his discovery came from his experience in multiple fields. Watson started out studying zoology, and then changed his study of interest numerous times, dabbling in bacteriophages, tobacco mosaic virus, and, of course, nucleic acids and proteins ("The Double Helix"). All of these ended up contributing to his success. His ability to think further than a single field and research different topics greatly influenced his experience with biology. Watson is not terribly judgmental; he understands different people's viewpoints, which gave him diverse knowledge essential to meeting his objective.

|

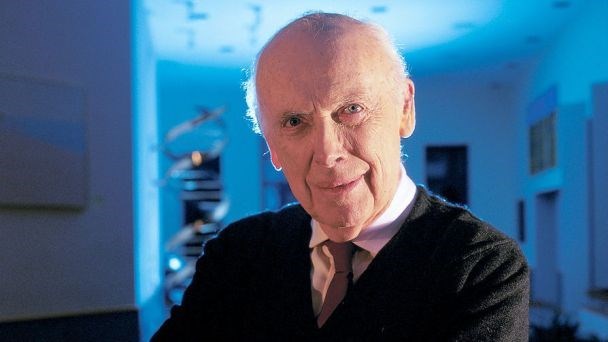

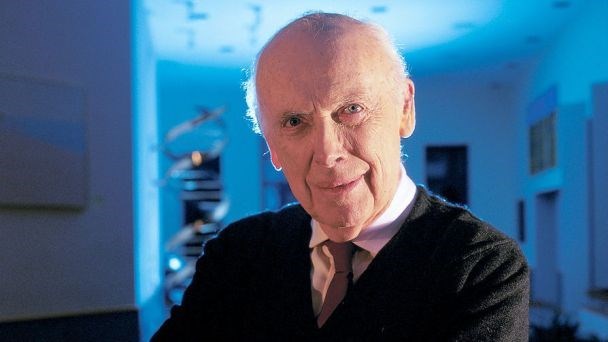

| Watson during his Big Think interview (http://bigthink.com/the-voice-of-big-think/james-w) |

Watson's objective for finding the DNA's structure was neither fame nor wealth, but rather the humble and optimistic hope to improve the lives of people all around the world. He mentions that he does not believe that he should have won the Nobel Prize, instead preferring to be remembered for something different: "I wanted to improve the world, make better life for other people. So, you know, I think I was lucky enough by becoming very, very famous very early that I could think about other people more"("James Watson"). Fame often consumes people and they give in to greed, losing sight of their original goal. Watson kept a tight grasp on his goals and used the publicity to his advantage. He made lots of new acquaintances and doing so kept him grounded. He is also aware that, despite all his idealistic hopes and dreams, his time is limited: "Because I want to stop cancer. You know, I saw a young uncle of mine that, you know, young children, he died when I was 20 years old. So, you know, so if you can do it, do it. So, you know, you can't do everything"("James Watson"). Humans are mortal and there is only a certain amount of actions one can accomplish within their lifespan. Watson wants one of those accomplishments to be putting a stop to cancer, or, at the very least, contributing to a cure. He is incredibly optimistic as he says that he thinks they will win against cancer soon. Watson is a modest man with brilliant goals that he works endlessly to meet.

An example of Watson's selflessness is his passion to teach aspiring scientists so they can go on to positively affect the world. "After a two-year stay at the California Institute of Technology, Watson accepted a position as professor of biology at Harvard University in 1956 and remained on the faculty until 1976. In 1968 he became the director of the Cold Spring Biological Laboratories but retained his research and teaching position at Harvard" ("James Dewey Watson"). While he was teaching at Harvard, Watson also wrote a number of books and worked as the director of the Cold Spring Biological Laboratories, which was a lot of responsibility to balance. He was very dedicated to his job; his book The Molecular Biology of the Gene became the first molecular biology textbook to be used by multiple universities ("James D. Watson"). Watson's devotion to his work can be traced to his life-long goal of wanting to teach: "My whole life has been basically trying to find intelligent students or, you know, highly motivated students and giving them an opportunity to do good science" ("James Watson"). Watson defines "good science" as science that is capable of affecting more individuals in a positive way. He hopes that his guidance will motivate his students to become proactive and do something that will ultimately change the world. The amount of work Watson has put into educating students and teaching them how to become great scientists is a brilliant trait that made a brilliant man.

Watson's acceptance of individuals, motivation to stop cancer, and enthusiasm for spreading knowledge are heroic qualities that should be acknowledged. His flexibility about conflicting views, his determined yet modest stand to help those who are less fortunate, and his eagerness for the younger generation to carry on his objective make him a hero to be admired. All of these traits point directly at Watson's goal: to make the world a better place, and he has condensed all of them into his book, The Double Helix: "His intention was to present an honest, accurate account that would naturally include the bad along with the good aspects of how science gets done" ("The Double Helix"). Watson wrote his book like a novel, telling how the people and process of a discovery may be more important than the flat research itself. He writes in simple terms that anyone could understand, doubling back to his love for educating. At one point in his life, Watson too was a child wondering about the vast world he lived in. Perhaps being on Quiz Kids sparked Watson's success in life, but he is so much more than a 12-year-old answering questions on a radio show. He is a hero.

Works Cited

"James D. Watson." Notable Scientists from 1900 to the Present. Ed. Brigham Narins. Detroit: \Gale Group, 2008. Biography in Context. Web. 11 Dec. 2013.

"James Dewey Watson." Encyclopedia of World Biography. Detroit: Gale, 1998.Biography in Context. Web. 9 Dec. 2013.

"James Watson: The Double Helix and Beyond." Talk of the Nation: Science Friday 16 Nov. 2012. Biography in Context. Web. 11 Dec. 2013.

"The Double Helix." Nonfiction Classics for Students: Presenting Analysis, Context, and Criticism on Nonfiction Works. Ed. David M. Galens, Jennifer Smith, and Elizabeth Thomason. Vol. 2. Detroit: Gale, 2001. 72-96. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 11 Dec. 2013.

Page created on 4/6/2015 12:00:00 AM

Last edited 4/6/2015 12:00:00 AM