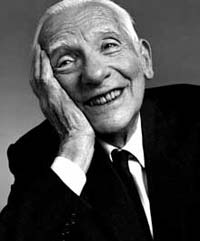

Dr. Bernard Lown

Cardiologist, Social Activist, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate

It would not have been a surprise if renowned cardiologist Dr. Bernard Lown had won the Nobel Prize in Medicine. After all, this Professor Emeritus at Harvard and founder of the prestigious Lown Cardiovascular Center invented the DC defibrillator, the cardiovertor and introduced the use of the drug Lidocaine to regulate disturbances of the heartbeat--research innovations that have unquestionably saved millions of lives.But the Nobel that Dr. Lown accepted in 1985 was for peace, in acknowledgment of his work on another large-scale lifesaving project: the cofounding, with Russian physician Dr. Evgeni Chazov, of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War. The organization now boasts over 145,000 physicians from 40 countries, brought together to secure what Dr. Lown has called the most fundamental of all rights: the right to survival.

His activism since the Nobel has had an equally profound impact on world health. His international bestseller The Lost Art of Healing focuses on the unique responsibility of the physician to listen to, engage with, and care for a patient, despite the interference of the economies of medicine. Many physicians believe that it should be required reading at every medical school in the country.

In response to some of the same issues, Dr. Lown also co-founded the Ad Hoc Committee to Defend Health Care, a not-for-profit organization for physicians who believe that health care is a fundamental human right, and one that should be guided by "science and compassion, not by corporate self-interest."

Dr. Lown's advocacy has global reach. In 1988, he founded SatelLife, an international organization that uses a network of satellites, ground stations, and e-mail to send desperately needed, up-to-date medical information to medical professionals in the developing world, where poverty and disease take a terrible toll. Originally conceived as an answer to the Strategic Defense Initiative, which was designed to put weapons of mass destruction into space, this network of lifesaving communication now encompasses over 120 countries and 20,000 individuals.

Whether his focus is on individual hearts, the practice of medicine, or the world itself, this eminent physician embodies the very definition of a healer.

|

In 1995, I began to think about this matter of heroes and heroism, and what that might mean during this sordid atomic age. If one followed the media, the world was peopled with criminals, rakes, and rogues. Perhaps to make myself feel better, I began to keep a list of people I considered to be heroes, thinking that someday I would write a book about them. The list grew to about sixty-five names, then other tasks displaced this hobby and I forgot about it. When I was asked to participate in this project, I found the list and found it fascinating.

Most of the people on the list are people that nobody has ever heard of. People like the artist Gunter Deming, who has placed small brass plaques that he calls "stumbling blocks" outside of the houses of people killed by the Nazis in Cologne, so that as you walk, you can’t help but think of the atrocities that transpired, and of German culpability in those atrocities. Or Jules Gerard Saliege of Toulouse, the Archbishop of Toulouse, who issued the first pastoral letter decrying Vichy policy on the Jews. Or Tamar Golan, the Israeli ambassador to Angola, who stayed on after his appointment to do landmine cleanup with the Angolan government. Or Raphael Lemkin, who spent a lifetime working for the United Nations to adopt the Genocide Convention.

I think of Ahmed Snoussi, a Moroccan comedian who was banned from performing his particular brand of political humor because, as he says, the government cannot laugh and cannot bear to have anyone else laugh either. Imagine--this man's sense of humor has made him an outlaw!

So, when you ask about heroes, clearly I have many--my wife Louise foremost. And I admire many of the people I have had the good fortune to know, like Willie Brandt, Olof Palme, Desmond Tutu, James Grant, Halfdan Mahler, and Mikhail Gorbachev. But if I had to winnow out one person from the many whose moral courage has inspired me over the course of my life, it would be my friend Joseph Rotblat. For me, he is the person who truly embodies what it means to be a hero.

I think of a hero as someone who, over a lifetime, performs deliberate, carefully thought-out, unique acts that demand moral courage. These are acts that anyone could, but no one else dares, do. The impact that a single courageous good deed can have is enormous! Just one such action may launch ripples to the eternity of time.

|

| Joseph Rotblat |

I chose Joseph Rotblat because he took more seriously than anyone I have ever met Einstein's admonition to scientists: "Concerns for man and his fate must always form the chief interest of all technical endeavors. Never forget this in the midst of your diagrams and equations." In 1955, Joseph Rotblat was one of the signatories of the famous Russell-Einstein Anti-Nuclear Manifesto. In 1957, he was cofounder of the Pugwash Conference on Science & World Affairs, one of the leading authoritative bodies on nuclear arms control and disarmament, and in 1958 he cofounded the UK Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. In 1995, he and the Pugwash movement were the recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize, and he is now Sir Joseph Rotblat--which is all the more interesting because the British government disowned him completely at one time.

Joseph Rotblat was born in 1908 to a wealthy family in Warsaw, but their fortune was destroyed in World War I. By fifteen, he was on his own, completely unschooled and impoverished, and working as an electrician. But he loved books and learning, and studied by himself, eventually applying to the famed Warsaw University. It seemed impossible: there were 55 applicants that year for three spots, and there was a well-established institutional bias against Jews, but despite these obstacles and the fact that they had never before admitted someone without formal schooling, Rotblat won one of the three openings.

Once accepted, he gravitated to the primitive biologic/radiologic lab as a researcher. He was working with a minute amount of radium in solution with a 27-second half life, but they wouldn't let him move the Geiger counter he needed for his work close to his workstation. So he had to race, carrying his radioactive cargo, three floors down to the basement to use the counter. The only way he could do it in time was if he took entire staircases in a single bound. The University finally permitted him to move the Geiger counter--but only after he'd broken a leg.

|

| Rotblat accepts the Nobel Peace Prize (www.nobel.org) |

Rotblat's brilliance as an investigator meant that his lab was competing in the discovery of radionuclides with the famous Enrico Fermi’s prestigious team, then in Rome. James Chadwick, the Nobel Laureate who had discovered neutrons, took note of this young scientist in Warsaw, and he invited Rotblat to his Liverpool laboratory. Rotblat arrived in England just before September 3, 1939, at the very outbreak of World War II. The Holocaust consumed his entire family, including his wife.

Rotblat was among the first people to comprehend the colossal implications stemming from the fission of uranium. He told me once that his first reflex, when the enormity of it had sunk in, was to put the whole thing out of his mind like the first symptoms of a terrible and fatal disease, in the hope that it would just go away. At the same time, he was absolutely overwhelmed by fear, knowing that the most advanced research in radiation physics and the most seminal discoveries had been made by the Germans. He felt sure that someone in Germany must also have come to the same conclusion, and that they would move ahead with this research to develop some sort of device, with the most devastating consequences.

That conviction led him to accept an invitation from Chadwick to go to Los Alamos as part of the scientific alliance between the British and the Americans proposed during the Roosevelt-Churchill summit in Quebec in 1943. There was a catch--only British citizens were permitted to participate. Although he was immediately offered British citizenship, he turned it down out of respect and loyalty for Poland, which was under savage German occupation at the time. He had hopes that he would eventually return to find his family and to help to rebuild that shattered country. General Leslie Groves, the tough-minded director of the Manhattan Project, brooked no deviations. It is a mark of Rotblat’s distinction that an exception was made for him.

The act of heroism that defined the rest of his life came in December 1944, when he was working in New Mexico on the Manhattan Project. He concluded that the Germans had abandoned the bomb, which meant that the American justification for this appalling project had vanished; there could simply be no reason to continue building such an infernal device. When he reached that conclusion, he resigned immediately and left Los Alamos. There were two thousand scientists involved, all with the same information--and yet not one of them did what he had done.

As a foreigner, he was immediately suspected of disloyalty; he was called a traitor and investigated for being a Soviet spy. This went on for years, during which time a trunk, filled with memorabilia and photographs of his wife and his family--his only material link to his childhood, his family, and to his homeland --was stolen by intelligence agents and never returned.

Rotblat returned to Britain but couldn't work in physics, as he could not gain clearance because he was still suspected of being a spy. For many years, he was watched by intelligence services. So he went to work at St. Bartholomew's Hospital, and over the next thirty years became one of the leaders in medical physics, developing international standards for radiation protection. In radiation biology, he remains without peer.

Joseph Rotblat is my hero because, despite surveillance and persecution, he remained utterly unswerving in his quest to rid the world of lethal genocidal weapons. Here’s what Bertrand Russell, whom I consider to be one of the finest philosophers of the twentieth century, wrote about Rotblat in his autobiography: "He can have few rivals in courage and integrity and complete self-abnegation, with which he has given up his career to devote himself to combating the nuclear peril as well as other, allied evils. If ever these evils are eradicated and international affairs are straightened out, his name should stand very high indeed among the heroes."

Page created on 2/7/2010 12:00:00 AM

Last edited 8/28/2018 1:23:37 AM

Copyright 2005 by The MY HERO Project

MY HERO thanks Dr. Bernard Lown for contributing this essay to My Hero: Extraordinary People on the Heroes Who Inspire Them.

Thanks to Free Press for reprint rights of the above material.