|

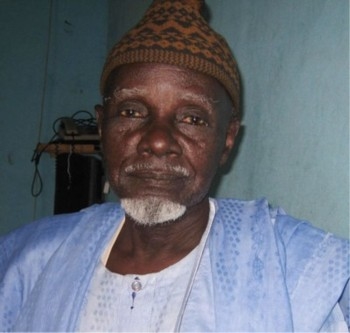

| My father and me (from Cheikh Darou Seck) |

For a long time I had decided not to tell about the story of my father, Malick Seck. Maybe I feared that I would not be objective enough or I would not really remember the most important parts of his story. Or maybe it was due to the uneasiness one always feels to tell about one’s family. But when I really faced the matter I knew that I hadn’t forgotten the least thing about his worth living life, and I knew also that I would stick to the truth of the facts about his life. Then I came to realize that his story might be a source of inspiration to many people for two main reasons: the many positive things he did for his community and the way my father educated his children.

Malick Seck (my father) was born in 1923 in a place called Merina Samb, deep in the country side of Senegal. He is a Mourid that is a disciple of Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba the founder of Mouridism, the biggest Muslim brotherhood in Senegal. It teaches peace and tolerance and for the Mourids “work is prayer”. As any Muslim child he went to a Koranic school and learned to memorise the 60 hizibs (parts) of the Koran until the death of his father. Then he left his home place to go and look for a job in Thies, the nearest town. At that time getting a decent job was very hard, especially for people who did not go to western school. But as he was a very resourceful man he managed to find a job in Thiès where he worked in the maintenance of the railway. Then he left Thiès to go to Rufisque, some 30 kilometers from Senegal’s capital Dakar, where he found a position in a plastic shoe factory for some years.

In 1968 when my father left the small coastal town of Rufisque to go to pay a visit to a friend in Joal, 114 kilometers south-west of Dakar, little did he know that that big village on the coast sung by Senghor, the president poet (Senegal’s first president), was going to be his home for the rest of his life. Seeing that the place was suitable for his job (he was a baker at that time) he settled down and started baking and selling bread and cakes. A few months later his little family (me, aged four, my mother, my elder sister, Marieme and younger brother, Pape) joined him. Just like the people in Telegraph Road, a song by Dire Straits, we never went further and we never went back. We simply settled in Joal where all the rest of my brothers and sisters were born some years later.

Naturally quickwitted, good natured and generous, people-oriented and a speaker of many languages like Wolof (his mother tongue) Arabic (though he never went to Arabia), French (though he never went to school), Bambara (the most spoken language in neighboring Mali) and some other local dialects like Serer and Pular), my father became rapidly popular in Joal and soon became the spokesman of the Wolof community in that village mostly inhabited by the Serer (local ethnic group), pleading for them in matters of local politics.

At the time of this story we were living in the port. Well it was not exactly a port but a place where fish were treated and conditioned before being transported to the other regions of the country. Our home rapidly grew into the meeting place for the many drivers and other fishmongers who would sit in the shelter made by my father to wait for their lorries to be filled with fish or their fishing boats to come ashore.

At that time any stranger in town who didn’t know where to stay would be advised to look for Malick Seck’s house. “Go to Malick Seck’s home and you will have a place to spend the night,” people would tell the stranger. Some of these strangers were remote relatives and some we even did not know.

Once the stranger found our home he would tell my father his name and where he came from and would politely request for the permission to spend a night or two. My father would just say: “This place is open to anybody. You can stay here until you find a better place.”

Most of these strangers used to be seasonal. They would come to Joal after the rainy season to look for enough money to make it to the next rainy season. Some of them only left our house after many years, when our family grew so big that there was no more room for them. -It was so for Mamour, a Gambian boy who was finally in charge of Mourid that was the only horse we ever had. -It was the case of Mass, a young man who came from the centre of the country and who turned out to be a one of the best basket makers this planet ever saw. -It was the case of Maguette Walo who had a particular song he would sing only when lunch was served. Finally everybody knew about Walo’s lunch song. -It also was the case of father Cheikh who turned out to be the best friend of my father.

It was the case of so many people that I cannot possibly name them all here. They stayed in our family’s house so long that some of them became members of our family. Many of these people were so well settled in our house that people thought there were blood ties between them and my father. Yet the first day he knew about their existence was when they came to ask for a permission to spend one night or two.

Opening his home to strangers was not the dominant trait in the personality of my father. He also was the first to collect money to send home a poor man who died in Joal and who did not leave any money to take him back to his hometown. My father would go to all the workshops and shops of the town and collect so much money that not only could the dead man be sent home but some of the money could be used for the funerals in his birth place. Ever since that day whenever someone died, especially the members of the Mourid brotherhood, my father was the one who collected the money so that the corpse could be sent to TOUBA (Mourid people are buried in TOUBA when they die).

|

I remember that one day my younger brother was having a nasty fight with a kid of the neighbourhood. A man named Saliou came to separate the two kids and asked who the fighting boys were. When he was told that one was the son of Malick Seck, he brought him to our home and asked to see my father. He was out. Then Saliou said:“I will never permit any boy to beat Malick’s son. Never ever”. “Because”, he went on, “I know that when I die Malick Seck is the one who will collect the money for me. He will find a car to take me to TOUBA for my final journey to the other world. I will not pay a dime. This is why I will never let any boy bully his sons.”

Saying this he turned and left. It is true that the man was a bit drunk when he said so. But the amazing thing is all he predicted happened exactly the way he said it. The day he died my father collected money and managed to find a car for the transportation of the corpse to TOUBA.

I recollect that my father even fundraised for people who simply needed to get back to their native place and who could not, being too poor or overcome by hardships and life’s setbacks. He never hesitated to stop his own work to help a needy person. This was basically my father’s community life.

Another regular activity of my father was getting people out of police hands. At that time it was not rare to see the police organize night patrols to arrest people who go out late and put them in a little cell for the rest of the night. Oftentimes, there were people my father knew among these night victims of the police and who could not pay the 3000 CFA fine (about 6 US dollars) to recover their freedom. They would simply send for my father to come and plead for them or guarantee their payment. Then the chief of the police who knew my father well would let them go upon his words. Sometimes my father even paid the fine with his own money and waited for the guy to pay him back whenever he got the money.

Many knew my father as Baay Malick, or Father Malick. Many of these people who turned to my father when they found themselves in trouble simply see him as the father they left in their village. Besides, he solved their problems, as their fathers would probably do if they were around. So, Baay Malick Seck is far well-known in Joal, though the little coastal village has become quite a big town.

To my father, money had never been a serious matter. It was a matter of having it or not. I don’t think that my father was ever able to save money for more than two or three days. He always kept whatever money he got in his pocket and gave some to whoever asked. I can still hear my mother telling him: “Malick, money will never grow in a pocket”

Though he had a shop for some time, my father never was much of a trader. He never quarreled about money. He would rather let the other have it. He used to talk about himself saying: “Malick will never lose his dignity because of a thing you leave behind when you die! Never ever!”

“If a man is not well educated, how can he educate his children” I think that the most outstanding trait in my father’s personality is his strong loathing of violence and his being good natured and a good storyteller. He told us stories when we were kids and he still tells us stories. My father always has a story handy to tell. The stories are mostly jokes or funny stories that make us laugh. Some of them were real and some were imaginary. I think that he simply hated to see people being sad.

I remember that we used to cluster around him as he told stories about his native place which is very distant from Joal. These are sometimes stories from his childhood. Some of these stories, I am sure now, were meant to help us understand how to find our way in life and how to learn to share and accommodate with people. In one word, how to leave a peaceful life with your neighbours. He used to say: “I can live with a snake in one single hole and he will never bite me”

Consciously or not there are many things that I simply inherited or imitated from my father. Many ways in my present behaviour originate from the way my father used to behave or what he used to tell us. His love of literature and reading (My father read a lot of Arabic. He told us the whole life of William the Conqueror he read in Arabic) led me to read hundreds of books (including Dostoievski, Stephen King and John Grisham), and his being polyglot aroused my interest in languages. He used to say that “beating a child doesn’t take you anywhere. If a man is not well educated how can he educate his children”

I remember my mother, upset by the way my father used to treat us, saying:“Malick, stop spoiling the kids! You never educate your sons?” But soon she would be there listening to whatever story my father was telling us and which would always end in a burst of laughter.

|

My admiration for my father is boundless and I always wonder whether I will be able to do for my children what he did for us. If we are respected and looked upon as a good family in Joal, it is due to the tremendous humanitarian work of my father and his positive actions in his community.

Today my father is a popular elderly man, loved and respected by his community.

When I was a kid it was not rare that I would meet a man who would ask me: “Are you Malick Seck’s son? “Yes.” I would answer. Then the man would simply reply “Why, you have a good father.”

Written by Cheikh Darou Seck Dakar Senegal

Page created on 6/10/2011 1:16:22 PM

Last edited 1/5/2017 11:05:28 PM