|

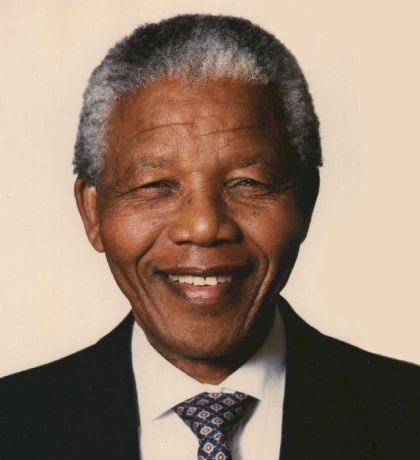

| Portrait of Nelson Mandela (http://photos.codlib.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/11/nelson_mandela.jpg) |

The judge’s voice rings out, calling the witness to make his statement. As the 46-year-old African man stands up, a hushed silence falls over the audience. Nobody in this all-white courtroom respects him, but they cannot deny that he radiates an aura of calm and power. As he begins to speak, the people show no signs of caring but are secretly captivated by this man’s ability to motivate, to inspire, to convince. In the end, prejudice wins over reason and the jury sentences him to life in prison, but his final statement will eat away at the minds of his jailers for the next 27 years:

During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to the struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But, if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die (qtd. in Brink).

|

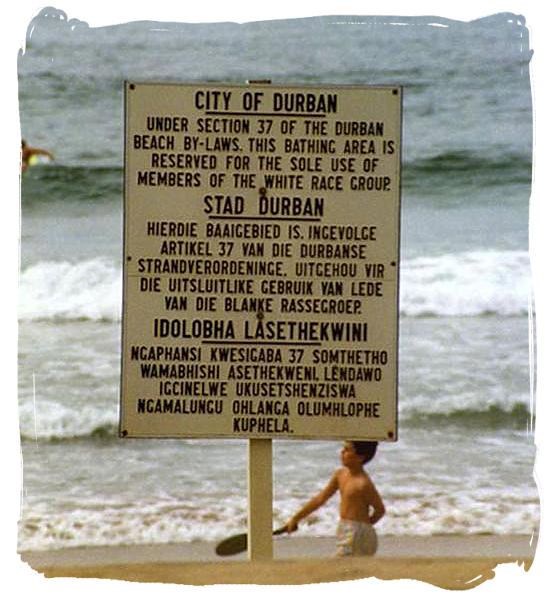

| Apartheid Sign in Durban, South Africa (http://www.south-africa-tours-and-travel.com/history-of-south-africa.html) |

Born on July 18, 1918 in Umtata, a part of the Trandskei territory of South Africa, Nelson Mandela grew up in obscurity. The South African government regarded his town as just another of the plethora of small, uncivilized villages. As a result, the native Africans in his town and beyond were severely oppressed and legally inferior to the white immigrants under the system of racist laws called apartheid. They were second-class citizens in their own country! From early on, Mandela demonstrated ambition by declining his right to take over as chief of his tribe, and instead, pursuing a legal career (Saunders). He attended the University College of Fort Hare and the University of South Africa, and during his time at both institutions the injustices that he saw committed daily under the legal protection of apartheid shocked him. He later spoke of these occurrences: “You will also recall the revolting story of a farmer who was convicted for tying a labourer by his feet from a tree and had him flogged to death, pouring boiling water into his mouth whenever he cried for water” (Mandela). As a result of these shocking behaviors, he joined the African National Congress in 1944, working to end the oppression of the black South Africans.

|

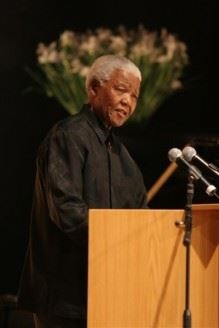

| Nelson Mandela giving a speech (http://www.nelsonmandela.org/images/uploads/8) |

Mandela traveled around the country, giving speeches and searching for men and women to join the ANC. At first, the majority of people flatly refused his plea. Years of fighting for an end to the corrupt system of government had led to nothing but misery for the native South Africans, and as a result, they had simply stopped trying. Although the white supremacists had drained much of their hope, Mandela told them the ANC’s goal of defeating the government and establishing a fair democracy was indeed possible. Without his inspiration and leadership, the people might not have ever had the motivation to fight the undeniably discriminatory apartheid. This purely South African system was not a new-found concept-–the all-white government had been perfecting their system of legal racism for so long that it had practically become a science. Because of this, the odds of a successful revolution occurring were infinitesimally small. As André Brink of Time Magazine puts it, the revolution had “little hope of success in a country in which centuries of colonial rule had concentrated all political and military power, all access to education, and most of the wealth in the hands of the white minority. The classic conditions for a successful revolution were almost wholly absent: the great mass of have-nots had been humbled into docile collusion, the geographic expanse of the country hampered communication and mobility, and the prospects of a race war were not only unrealistic but also horrendous.” The fact that “the great mass of have-nots had been humbled into docile collusion” could not be more meaningful– revolutions need masses of people if they are to occur successfully, and those people must want their freedom enough to make sacrifices for it. Like tamed circus animals, the native South Africans had been beaten one too many times to cause any mischief again. At least, that is what other leaders who had tried to start a revolution assumed. Mandela refused to adhere to this previously unchallenged assumption--he believed that the people had one last iota of fight in them, and worked tirelessly to show them that. His emotional and motivational serenades culminated in his 1953 speech to the ANC Congress: “You can see that there is no easy walk to freedom anywhere, and many of us will have to pass through the valley of the shadow (of death) again and again before we reach the mountain tops of our desires... Dangers and difficulties have not deterred us in the past, they will not frighten us now” (Mandela). Through this speech and many more, Mandela managed to do what no man had dared to do before. His words and his spirit served as a figurative lighthouse of hope, its beams of light reaching into the hearts of the native South Africans, confirming their hopes and prayers of a brighter future. Mandela became a veritable map, showing the black people of South Africa where to go and what to do, but more importantly, giving them something concrete to latch their hopes and dreams onto. More than a leader, a planner, and a sacrifice for the cause of human rights, Mandela was a symbol of hope who managed to take an entire population of oppressed souls and give them the courage to fight back.

|

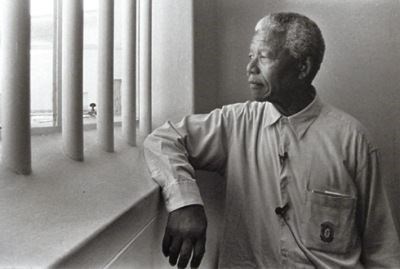

| Robben Island, South Africa (http://www.travelbeat.net/selfdiscovery/images/435RobbenIsland.jpg) |

Mandela had indeed made an outstanding accomplishment through his speeches for the ANC and, as a result, the African rights movement began to pick up steam. Although this triggered a rush of support from the black majority, it also alerted the government. Interest turned into investigation, and the government began to crack down on the ANC and other rebel groups. Mandela went into hiding, but the government caught him and put him on trial after a year of cat-and-mouse. The court found him guilty of treason and sentenced him to life in prison. He spent 18 years of that sentence on Robben Island doing hard labor, but eventually the authorities moved him to solitary confinement because he was exerting too strong of an influence on the other inmates ("Mandela, Nelson (1918-)."). During this time, Mandela had become a household name and international figure symbolizing the struggle for human rights. After nine more years, the new president of South Africa, F.W. de Klerk, released him on February 11, 1990 under significant national and international pressure.

|

| Nelson Mandela in prison (http://technostudies.wordpress.com/) |

Although Mandela started off as just a symbol of hope to blacks, during his time in prison, the whites began to realize that there was something drastically wrong with the government, especially since it had led them to economic failure. Mandela quickly became a cross-race representation of “the struggle against government-mandated discrimination. With his magnetic personality and calm demeanor, Mandela was widely regarded as the last best hope for conciliating a peaceful transition to a South African government that will enfranchise all of its citizens” ("Mandela, Nelson (1918-)."). The key value that Mandela embodied was the idea of a nonviolent evolution to a democratic government. In his ideal society, there would be no difference between the whites and the blacks in terms of governmental power. The two might never be able to fully coexist (though that was another of Mandela’s goals), but they would at least be able to live in the same country without “white domination” or “black domination” (Mandela). Therefore, when the government released him, Mandela became “the best hope for a political settlement that will guarantee them [the whites] a future” ("Mandela, Nelson (1918-)."). After his release from prison, both whites and blacks consolidated their efforts to make South Africa a better place, as best exemplified by the cooperation between Mandela and President de Klerk in transforming South African government into an unbiased democracy. By proving his merit as an inspiration to the blacks, Mandela gave himself bargaining power with the white government and was thus able to peaceably negotiate the terms of a new South African democracy.

In 1993, Mandela and de Klerk shared the Nobel Peace Prize for their work in the establishment of a South African democracy. Mandela won the first open elections of this democracy, and worked to end all traces of apartheid and racism that the country still had, creating a new constitution in 1996. He had finished his work for the ANC, and thus resigned from the organization in 1997. Mandela’s presidential term and work towards his ideal of a free South Africa ended in 1999, though he has continued to actively advocate peace in Africa ever since.

Throughout his life, Mandela demonstrated perseverance and a willingness to put everything aside for his cause, even when taking the easy way out would have lured any other man like a bee to honey. Because of these qualities, he is not only a hero, but a true inspiration for future generations. Mandela was not on a star-crossed path on his voyage to racial freedom. He had the freedom of choice, right from the very beginning. In his early days, Mandela chose to go to law school, a notoriously difficult career choice, instead of living a relatively peaceful life in the countryside. Mandela might have even made a successful lawyer, but instead he chose to go down a path that would lead to sacrifice and anguish; it was also the only path that would give him the satisfaction of doing something worthwhile (Brink). This sacrifice for the good of man is a quality that should be embodied by all leaders, and as such, Mandela is a role model for anybody aspiring to become any type of leader. Later on in his life, Mandela went to jail for doing what he believed in. Although that was heroic in itself, Mandela emerged from his 27 years in prison ready to forgive his jailers. He was not interested in petty human pleasures like revenge when his cause was on the line! This proves an enormous dedication to his goal of a democratic South Africa and a perseverance unmatched by many of his predecessors. Furthermore, it exemplifies a willingness to suffer for the good of the South African people--a selflessness that the human population could learn from.

Through his charisma and the power of words, Nelson Mandela inspired the native people of South Africa to stand up for their rights and later guided the entire nation into ending the corrupt system of apartheid. His nonviolent tactics and emotional speeches prove to humanity that it is indeed possible for one man to represent two opposing races, and to heroically change the world by doing so. Furthermore, his perseverance in the face of extreme odds and countless possible paths demonstrates his steadfastness and selflessness, and proves that he should be regarded as an inspiration to future generations.

Nelson Mandela was born Rolihlahla Mandela; a “primary school teacher with delusions of imperial splendor” gave him his English name. His native name means “one who brings trouble upon himself” (Brink). From his beginnings as the son of a rural farmer, to his speeches of truly epic proportions, to his 27 years in prison for the good of the African people, to his unparalleled way of peacefully negotiating the terms of a new government, and even to his ultimate success as the President of South Africa, Nelson Mandela did bring all of his suffering upon himself. But if every hero since the beginning of time had taken the easy way out, there is no doubt that the world would be a very different place.

Page created on 10/1/2010 12:00:00 AM

Last edited 10/1/2010 12:00:00 AM