|

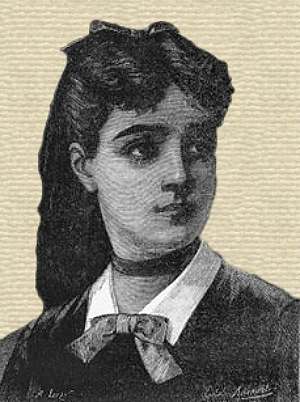

| Sophie Germain at the age of 14 (https://todayinsci.com/G/Germain_Sophie/GermainSop ()) |

There is, and has always been, ongoing debate about what constitutes a hero and what heroism truly means. Some people are more lenient with their criteria than others, and some have different ideas about what traits qualify as heroic than others. Personally, I believe that the true essence of heroism lies in a benevolent, meaningful contribution to the world and environment around you. Nowadays, heroism is more of a temporary, one-time event. The news often covers stories of people doing single heroic acts that gather lots of attention for a couple days, then soon afterwards are forgotten. However, the heroes out there whose contributions are smaller, yet more consistent, are largely overlooked. It is not necessary to be courageous or brave, nor to put yourself in danger to be a hero. The very concept of heroism is based on helping others, whether it involves being out and active in a community or whether it's done from the comfort of home. Either way, however, a person needs to embody certain character traits in order to earn the title of hero. These include, but are not limited to, benevolence, perseverance, and tenacity.

One such example of a personification of these traits is Sophie Germain. Germain was "...a woman who had to overcome a series of obstacles to rise to prominence in the mathematical world of the early 19th century." (Dunham 241). She was born on April 1, 1776 in Paris, France, the city where she would spend her life. As a child, she became interested in mathematics, and despite opposition from her parents, pursued the subject. Due to her gender, Germain could not attend university, and had to teach herself using books from her father's library and borrowed lecture notes from university students. She moved on to more and more advanced topics until she was more or less caught up with the mathematics of the day. From there, she began working on pushing the boundaries of mathematical knowledge. In order to be taken seriously, she disguised herself as a man, going by the pseudonym "M. le Blanc." She won a prize in 1816 for explaining an instance of vibrations in metal plates. In 1831, at the urging of Carl Friedrich Gauss, the leading mathematician of the time and one of Germain's correspondents, Germain was to be given an honorary doctorate from the University of Gottingen. Such an award would have been "a brilliant honor for a woman in nineteenth century Germany." (Dunham 242). This made it all the more unfortunate when she died, on June 27, 1831, before she could receive the doctorate. In order to be considered a hero, a person needs, at the bare minimum, to benefit the world in some way or another and to inspire others to do the same. Sophie Germain, a French mathematician and physicist, overcame many obstacles pertaining to her gender in order to pursue her passion for mathematics and eventually make several significant contributions to the field. Therefore, she is a hero.

|

| Bust of Sophie Germain (https://www.agnesscott.edu/lriddle/women/germain.h ()) |

Germain chose to defy what was considered normal for women and study mathematics, the landscape of which was dominated by men during her lifetime. Ever since her youth, she displayed interests that deviated from those of other girls her age, including her two sisters. When Germain was thirteen years old, the French Revolution began, and the world around her became filled with more turmoil. Due to the fact that she disliked conflict, she spent a large portion of her days in her father's library, as she "...studied mathematics on her own...her parents were so opposed to her behavior that she took to studying at night. They responded by leaving her fire unlit and taking her candles. Sophie studied anyway, swaddled in blankets, by the light of smuggled candles." (Merry and Smart). Germain refused to listen to her parents, who were so against her studying mathematics for no reason other than her gender. Fortunately, however, they eventually relented when they realized the futility of their countermeasures. Her tenacious actions demonstrate her passion for math despite the unapproving environment around her. Later in her life, after winning a contest by mathematically explaining vibrations in metal plates, Germain was awarded a prize from the French Academy. Although it took her three tries, as her first two submissions had gaps in the logic and slight errors, she succeeded in the end: "Winning this prize made Germain a genuine member of the French scientific community and she was then allowed to attend sessions of the Institut de France. This was the highest honor that the organization had ever bestowed upon a woman." ("Sophie Germain," Math). Despite the fact that she wasn't allowed to join the group, just permitted to attend meetings, it was still progress toward abolishing the stereotype that women couldn't do mathematics; Germain was the first woman who partook in the sessions that wasn't married to any of the other members. Despite this, however, her being a female was a heavy burden on her shoulders that prevented her from walking as far as she could have down the road of mathematics: "...her gender always kept her 'on the outside, like a foreigner, always at a distance from the professional scientific culture.'" (Merry and Smart). It is up to subsequent generations to ensure that no more potential is ever wasted again for such prejudicial reasons.

Although her gender left Germain unable to create a full career out of mathematics, she still achieved a myriad of wonderful results in the field nonetheless. One of the branches of mathematics that she contributed to was number theory. In short, number theory is the study of numbers and their relationships. While it sounds simple, the subject can get quite complex and abstruse at times. One of her most important results in number theory was her work on an unsolved problem called Fermat's Last Theorem: "Sophie Germain's foundational work on Fermat's Last Theorem, a problem unsolved in mathematics into the late 20th century, stood unmatched for over one hundred years." ("Sophie Germain," Notable). Fermat's Last Theorem was arguably one of the most difficult mathematical puzzles in all of history. Not only did Germain provide one of the first major results toward solving it since it was conjectured in 1637, but she also laid the foundation for the full proof that would come another 170 years later, which was based on her method. In addition to number theory, which is a branch of pure mathematics with few practical uses in real life matters, she studied applied mathematics as well: "Regarded by many mathematicians as France's greatest female mathematician, Sophie Germain was a creative and highly original thinker. Her contributions to the applied mathematics of acoustics and elasticity were of such quality that some scholars consider her to be one of the founders of what is called mathematical physics." ("Sophie Germain," Math). Thinking critically and creatively is an essential part of a mathematician's job, and Germain was able to do it better than most. Part of what made her successful at what she did was her ability to look at problems from a different perspective. However, some might argue that being a good mathematician does not necessarily make someone a hero. Their work might not have enough of a positive impact to create a real difference. Also, many mathematicians don't exactly embody the character traits that are commonly associated with heroism, especially those who are bitter and spiteful. Such people tend to have acrimonious relationships with others, and would not generally be considered heroes. In Germain's case, however, these arguments are not valid. Although she wasn't exceptionally kind or generous, she still deserves to be recognized as a hero for her work. The steps she took to reduce the social stigma associated with female mathematicians amplify her mathematical work and give it much more meaning and significance.

|

| The sign of the street named after Germain (https://www.agnesscott.edu/lriddle/women/germain.h ()) |

Sophie Germain faced many challenges - both societal and intellectual - and succeeded despite them. She was one of the few women of her time who had the audacity to pursue a higher education in mathematics. Due to the prejudice back then, women were discouraged from studying mathematics, so Germain had to find ways to teach herself. She communicated with some of the leading mathematicians of the time under a pseudonym to conceal the fact that she was a woman. Although they eventually found out her true identity, most still continued their correspondence with her nonetheless. Germain is responsible for several important mathematical results, both in pure and applied mathematics. This success, combined with her chasing her passion, inspired later women to go after their dreams as well. Germain's effort, combined with other women who followed suit, eventually led to a more unified scientific community, freer from irrational discrimination and prejudice. Today, Germain remains an inspiration for women, mathematicians, and those who are a combination of the two. Both her contributions to mathematics and society hold great importance: "Her prescient ideas on the unity of all intellectual disciplines and equal importance of the arts and sciences, as well as her stature as a pioneer in women's history..." ("Sophie Germain," Notable). However, the recipe to Germain's success could not have worked without the secret ingredient: hard work. She encountered countless obstacles on her mathematical journey, but in the end she persevered and succeeded. Her tenacity is admirable and inspiring; it makes one feel like they, too, could achieve greatness if they worked hard enough, no matter how disadvantaged they might be. Perhaps that is what a hero is. Someone who inspires and motivates us, a role model from which we can learn.

Works Consulted

Dunham, William. "A Sampler of Euler's Number Theory." Journey through Genius: the Great Theorems of Mathematics,

Penguin Books, New York, 1991, pp. 241-242.

Merry, Maisel, and Laura Smart. "Women In Science." Sophie Germain: Revolutionary Mathematician, San Diego

Supercomputer Center, 1997, www.sdsc.edu/ScienceWomen/germain.html. Accessed 10 May 2017.

"Sophie Germain." Math & Mathematicians: The History of Math Discoveries Around the World, edited by Leonard C. Bruno,

UXL, 2008. Biography in Context, link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/K1669000023/BIC1?u=powa9245&xid=a98f43bb.

Accessed 10 May 2017.

"Sophie Germain." Notable Women Scientists, Gale, 2000. Biography in Context,

link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/K1668000149/BIC1?u=powa9245&xid=711deda5. Accessed 10 May 2017.

"Sophie Germain." Science and Its Times, edited by Neil Schlager and Josh Lauer, vol. 4, Gale, 2001. Biography in

Context, link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/K2643411247/BIC1?u=powa9245&xid=586fbdaf. Accessed 10 May 2017.

Page created on 5/22/2017 12:00:00 AM

Last edited 5/22/2017 12:00:00 AM