|

Theodor Seuss Geisel , better known as Dr. Seuss, his pen name for several of his children‘s books, has indeed revolutionized, changed, affected, and perhaps even based not only through the way children’s writing and literature can be written, for though this is what he is normally thought of and is accounted for, but also the serious but insanely flawed world we have about us, what we need to do about it, what we can learn from it, and what will happen to it, not only then, but now, as well as in future times, when civilization will be in dire need of attention that would otherwise become corrupt and inane. He does this through his works - the many books, films, comics, articles and such - as well as his life (his doings) and how it contributed to the country as well as the world, and finally, his “moral aspect” personality, all of which his profound opinion of politics as well as serious world problems fell into place. In addition to this, Geisel has also revolutionized children’s literature through his ingenious usage of playful language, ridding of the lawful, overruling, tedious ways of previous author’s works. All of these are what Theodor Geisel is, what he is remembered for, what he has given to the world, and how the world will always need this fine, courageous, wise, witty, truthful, genuine, caring, unknown, rejected, positive, committed, crucial character in history.

Theodor Geisel had an ever prolonged and memorable life, and it, obviously, began in his childhood. The man was born in Springfield, Massachusetts, at Howard St., on March 2, 1904. He had two parents like any old child in the day, Henrietta Geisel being his mother and Theodor Robert Geisel as his father. His grandparents were German immigrants, as he and his family spoke German at home. Geisel’s grandfather owned a brewery shop called Kalmbach and Geisel Brewery, which his father inherited until the Prohibition, a time in US history in which it was illegal to sell or drink alcohol. This business loss had greatly impacted the Geisels financially. Many have speculated that Geisel had developed the passion and the skills to draw and cartoon through observing the animals at the zoo his father overlooked, for he had become the head of public parks at the place, in which the zoo was one of such public parks, instead of working at his grandfather‘s brewery. Despite this, his father had really acquired this job when Geisel was in his late 20s. Geisel claimed that his mother was the one who gifted him with the ability to rhyme skillfully, for she had used such rhymes that she had learned when she was younger, particularly when she had worked in her father’s bakery as she sold pies, to sooth him and his siblings to sleep, Marnie, the eldest, and Henrietta, who died at 2 because of pneumonia and cannot be fully considered as one of Geisel’s siblings. Aside from the parent’s influence in his inspiration for becoming a well-known author and illustrator, Geisel was always fascinated by books and enjoyed going to the book store, reading books that would otherwise be considered for peoples much older than him at age 6, perhaps younger. Some of such books had possibly influenced his clever form of rhyme, while others toyed with his imagination. Such books that used rhymes to tell stories that could have done so included The Bad Child’s Book of Beasts (1896), More Beasts for Worse Children (1897), and Cautionary Tales for Children, Designed for the Admonition of Children Between the Ages of Eight and Fourteen Years (1907). All of these had rhymes in them, and were written for children as well, but instead of projecting the imaginative minds of children as Geisel did with his books, these books used fictional characters to teach children how to stay out of trouble, in a sort of ‘I’m an adult, do as I do!,’ sort of fashion, which was totally different. Despite such authors, Geisel had also been exposed to such books by creative artists, one of which is Peter Newell. One of his favorites by Newell was The Hole Book (1908), where an actual hole went through the whole entire book, as the book was all about where a bullet went, through several household items and such, and finally stopped when it had hit a cake and, in turn, stopped because of the strength of the cake. Also during his youth, Geisel was one of Springfield’s boy scouts, wherein he won an award for being in the top ten who sold the most U.S. war bonds, which was used to help pay for the military, though this was because his grandfather bought $1,000 worth of them.

|

Geisel had attended several schools throughout his life, as several others today normally do. He attended Forest Park School for kindergarten, Central High School for High School, and attended Dartmouth College for collage. The art teachers who had taught him within these years, in fact, disliked the way he drew greatly, and assumed he could never have a career in art when he grew up. It was said that he would always turn his canvas or paper or whatever media he was using upside down to make sure the drawing was even, which the teachers totally denied as a useful way to do so. When in high school at Central High School, he began his first publications on the school newspaper, the Central Recorder. Many of these included articles, as well as comic strips, though these would not be very distinguishable for Geisel’s work; these were more “primitive” versions of his. During these days, he was very active within the community of both his school and outside of school. He learned how to play the mandolin and the banjo. Then At Dartmouth, though he was studying for a major in English, he was also editor-in-chief for The Jack-o-Lantern, a humor magazine for Dartmouth, in which he made several comics for, and where his publicity for his art grew. The imagery and imaginative basics of his, indeed, fanciful creatures featured in several of his works had appeared in such articles, as well as through solitary “free time”. One such piece is “Our Own Natural History: The Woozle Bird.” In this piece, Geisel explains that this ‘bird’ as being born with broken left wings and, “… therefore cannot turn to the right while flying. The bird flies always in circles, and for that reason is fast dying out. The natives wait for the bird to become dizzy and fall to the ground, at which they approach cautiously and put salt on its tail. The bird is then unduly weighted down behind and has to fly upward in circles. At length the bird reaches the upper strata of air where the oxygen is scarce and finally suffocates and falls to the earth, where the natives gather them up in large quantities… The main commercial value of the bird lies in a secretion in the right foot, which is boiled out of the bird and used to make glue for postage stamps… The males are generally black with white stripes, and the females white with black stripes, and when resting in flocks are nearly invisible due to their resemblance to a modernistic painting.” But one night, the group, which included Geisel, were caught having a party with drinks - beer, etc. - which was against the law, for as I said before, the Prohibition of the US and other countries were occurring at the time, as it was illegal to sell or drink as such. Since that incident, he still wrote for the Jack-o-Lantern, but signing it under pen names, which is when he began using his ever so popular ‘Seuss’ pseudonym.

After Dartmouth, with a bit of financial assistance from his father, he

aimed his direction to getting a doctorate at Oxford University and

become a professor. Despite this, he began to dislike the studies he had

acquired at Oxford, and instead traveled round Europe to entertain

himself. During such studies, though, in a class on Shakespeare

punctuation, he met Helen Palmer, who was to become his future wife in .

Helen had seen Geisel’s doodles during classes, and perhaps could have

influenced him to become an author and illustrator by trying to convince

him to become one, seeing that he was, indeed, interested in the arts,

as well as literature. Despite this, Geisel realized that he would have

to get a job before he could do anything else in his life. This is,

maybe, where Helen’s influence came into place.

|

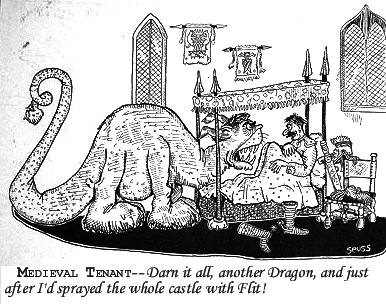

During the 1920s, he had begun his pursuit of publication, sending a

number of his works to several newspapers, trying to show his portfolio

to publishers in New York City, etc., etc. Eventually on July 16th,

1927, he had become published in The Saturday Evening Post, and this had

been seen by a particular Judge editor, in which he then became a part

of the staff. The first time Geisel had ever worked in a group to create

a particular published work was in Boids and Beasties, where in his

series of comics and sketches and such had begun to shape. One of such

comics involved a knight in bed with a dragon at the verge of consuming

him, with a caption of the knight complaining, “Darn it all, another

Dragon. And just after I’d sprayed the whole castle with Flit!” Flit

being a popular insecticide at the time, this had caught the eye of

several peoples, particularly of those who had a business in Flit,

particularly Mrs. Lincoln Cleaves who had read it. She had shown it to

her husband who worked for the company. Thereon, he began his career in

advertising, creating cartoons for Flit, Ajax Cups, Daggett &

Ramsdell, Ford, General Electric, Gilbert & Barker, Holly Sugar,

L.P.P. Co. Macy Westchester, NBC, News Department, Snyder & Black,

Standard Oil, Stromberg Carlson, and Warren Telechron. Several

advertisements were simply comics, such as in Flit, wherein he used the

catch phrase, “Quick, Henry, the Flit!” quite often, others booklets,

such as the advertisement he made for Stromberg-Carlson that featured

“Wild Tones,” the “… bad tones that escape from the back of your

speaker”. Despite the high payment he had for all these jobs, seeing

that his pay rose from the $1,300 per year at the Evening Post, to the

$3,900 per year he got by working for Judge, then the $12,000 he got per

year for advertising for Standard Oil, and the fact that he had worked

in the world of advertising for 15 whole years, Geisel still disliked

the fact that there wasn’t enough variety that could be expressed

through these advertisements. Thus he began working as a political

cartoonist.

From 1941-1943, Geisel took his job as a cartoonist for the PM, a

newspaper in New York. In it, he drew over 400 political cartoons,

though most would not think of such a man as Theodor Geisel to create

such deep and negatory creations, and would not ever be regarded as a

political cartoonist.

Geisel not only served his country through the things he had made and

printed and published, but also by working for (all right, training

people who were in) the army. When he shifted his job yet again in 1943,

he began creating training movies for Frank Capra’s Signal Corps, in

which he learned how to animate. The series of movies he created

featured a man called Private Snafu.

The first book his works were featured in he, in fact, did not create himself. It was, in fact, by Alexander Abingdon, and the opportunity to illustrate it was given to him by Viking Press. The book, or in this case books, were Boners, More Boners, Still More Boners and The Pocket Book of Boners, all of which were published in 1931. Boners was quite a hit, ranking up to one of New York Times Bestsellers. The others did great as well, but in all, the publicity of their illustrations and their accompaniment with a children’s book. This directed him to try to publish a children’s book of his own. He began with And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street (1937), which is said to have struck him on a cruise ship called the Kungsholm, the rhythm of the engines inspiring him with the rhythm of each verse. Sadly, it was rejected by 27 different publishers, but he had finally met an old friend who used to go to school with him in Dartmouth and worked for Vanguard, so published it for him. He then began with several of his other books, such as The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins (1937), of which Vanguard also published, Horton Hatches the Egg (1940), McElligot’s Pool (1947), In I Ran the Zoo (1950), Horton Hears a Who! (1954), and the one he was and is most famous for, The Cat in the Hat (1957), all of which Random House published. As many might know, Geisel was challenged by a publisher that he would be unable to create a children’s book using only 225 basic ‘children-leveled’ words; he met the bet at 223. Sadly, 10 years after The Cat in the Hat’s publication, Helen committed suicide because of several illnesses she was experiencing. Despite this, Geisel remarried, his new wife being Audrey Stone Geisel, an old friend of his. He went on to write more books, resulting in 44 books in all, all of which gained publicity and sold several copies, and in general was a complete success.

|

The last book Geisel ever wrote was Oh, The Places You’ll Go! (1990), marking the time of his death only a year after it’s publication. Theodor Geisel’s death occurred on September 24, 1991, in San Diego, California.

Dr. Seuss’ influence on children’s literature is vital to today’s children’s literature in several forms and for several reasons. His books had changed the way such books tried to get across; rather than trying to teach children to not only make mistakes, but not to even make mistakes, to follow orders and to only do orders when they were told, etc., etc., he tried to express a child’s imagination and freedom, to ‘let loose’ not necessarily what one’s parents are trying to say, but what the world was trying to say. For example, in Cautionary Tales for Children, Designed for the Admonition of Children Between the Ages of Eight and Fourteen Years, by Hilaire Belloc, it tells of the story of Jim, “Who ran away from his nurse and was eaten by a lion…”

“Now just imagine how it feels

When first your toes and then your heels

And then by gradual degrees,

Your shins and ankles, calves and knees,

Are slowly eaten, bit by bit.

No wonder Jim detested it!…

The Miserable Boy was dead!

When Nurse informed his Parents they

Were more Concerned than I can say:-

His Mother, as She dried her eyes,

Said, “Well - it gives me no surprise,

He would not do as he was told!”

His Father, who was self-controlled,

Bade all the children round attend

To James’ Miserable end.”

Versus the view of lions and their interactions with the human, or indeed child’s, presence in If I Ran the Zoo:

“So I’ll open each cage. I’ll unlock every pen,

Let the animals go, and start over again…

A four-footed lion’s not much of a beast.

The one in my zoo will have ten feet at least!

Five legs on the left and more on the right.

Then people will stare and they’ll say, “What a sight!

This Zoo Keeper, New Keeper Gerald’s quite keen.

That’s the gol-darnest lion I ever have seen!”

|

The two differentiate because one sees the lion as a vicious opportunity to teach a little boy a lesson through shame and torture, while the other provides the animals as an animals that could potentially open up a child’s imagination and amaze others as well. This is one examples of the many that made Dr. Seuss’ mind and creations different from those before his, and powered the creativity, imagination, originality and publicity of those after him. Not only that, but his books made children actually pay attention with clever, fast paced and enjoyable rhyming literature and eye-catching, melodramatic illustrations - Geisel spent hours on end planning and sketching and brainstorming how the colors of pictures would make the illustrations more interesting, the rhymes and rhythms of which would be written, etc. - that made reading more amusing to not only children but as well as adults (when was the last time daddy fell asleep while reading that bedtime story?), and lessened the amount of diversion that the readers were once exposed to. Not only that, but the morals of these books were quite different from those before; going back to the examples I gave before from one of Hilaire Belloc’s books versus Theodor Geisel’s, many books before Theodor Geisel’s were particularly targeted at children, showing them what they should and shouldn’t do and how it would affect them. On the other hand, Geisel’s morals in his books went much deeper than that and had much originality and truth, and didn’t just point to the children who read it, but to the world and what it should do to certain problems, as well as everyday life not only as a child, but as an adult as well. For example, in Horton Hears a Who!, Geisel tries to explain that everyone should have a say in today’s society and today’s world, and as such should not be judged by physical appearance or doings - anti-isolationism. Then there’s Yertle The Turtle, wherein the moral is that one (person) cannot try to ‘take over the world’, as one could put it, but that everyone should be free in their own will - anti-fascism. The Sneetches talked of anti-racism. The Lorax went against pollution, and tried to make the point of protecting and preserving the wonderful irreplaceable environment that we live in. How The Grinch Stole Christmas! talked of how we shouldn’t base our happiness on objects that, in the end, don’t matter - anti-materialism. Finally, The Butter Battle Book tells of how silly war is and how fighting just isn’t the way to resolve a country's, including one’s own, problems and rights. Not only is all this amazing because of the significance of these morals, but also that they can be presented in a children’s book (all right, several of these books, in fact, were not designed for children but rather for adults, but many treat them as childrens books). If it weren’t for Geisel, perhaps children and the generations afterward would not be as creative and imaginative as they are today, and therefore not be as smart and work in a world that is continually searching for fresh, new, creative, imaginative minds. They would, therefore, not have very many rights, and in turn would lack such skills as being able to work independently, to collaboratively work in a group, to come up with exquisite ideas that could alternatively change the world, etc. This is why Geisel will always be remembered as a wonderful writer who revolutionized children’s literature and today’s generation and today’s future generation.

Page created on 3/9/2012 12:00:00 AM

Last edited 3/9/2012 12:00:00 AM