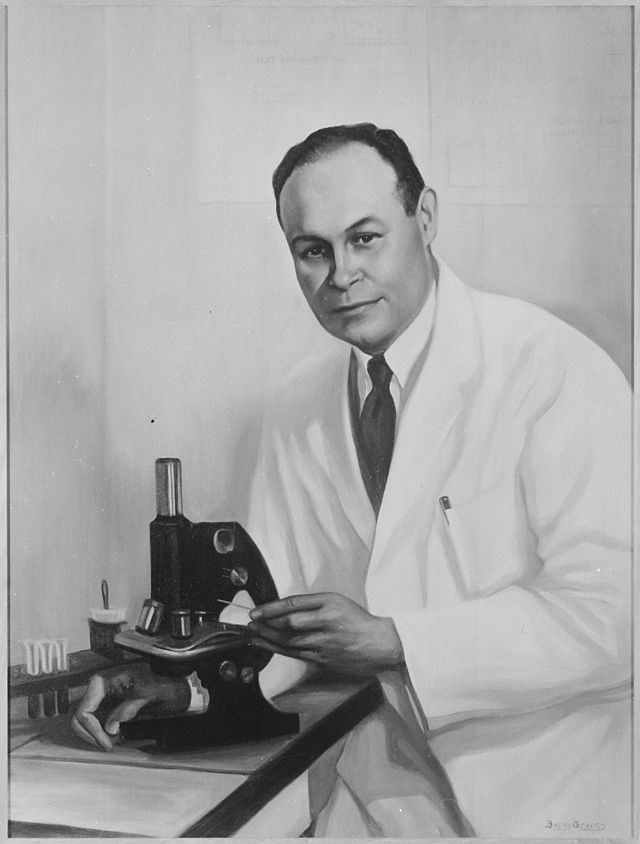

Dr. Charles Richard DrewBetsy Graves Reyneau via Wikimedia Commons

Dr. Charles Richard DrewBetsy Graves Reyneau via Wikimedia Commons

Dr. Charles Richard Drew was an African American surgeon and pioneering medical researcher. His ground-breaking research in blood transfusions not only saved thousands of lives during the second World War, but influenced the way that blood is stored in blood banks to be used for transfusions today. He was also a powerful advocate for racial equality, protesting racial segregation in blood donation.

Early Life and Education

Charles Drew was born on June 3rd, 1904, in Washington, D.C. His father, Richard Drew was a carpet layer, and the only member of color of the Carpet, Linoleum, and Soft-Tile Layers Union.[1] His mother, Nora, trained to be a teacher and knew the value of education. Charles was the eldest of five siblings, and all of them were encouraged by their parents to work hard in school and attend church every Sunday. The family lived in Foggy Bottom, a middle-class, interracial neighborhood in Washington.

Though segregation was still enforced in Washington at the time, many of the African American public schools in the area were excellent and served many successful families.[2] The school Drew attended, Dunbar High School, was widely recognized for its offering equal opportunities to all its students despite the social norms. Whilst at Dunbar Drew became an excellent athlete, exceling in both track and field and football. When he graduated from high school, Drew received a sports scholarship from Amherst College in Massachusetts.[3] During his time there, Drew became interested in medicine. As soon as he graduated from Amherst in 1926, he took a job as a football coach and biology and chemistry instructor at Morgan State University (then known as Morgan College) in Baltimore, to save for medical school.[4]

Because of the segregation laws in place at the time, applying to medical school was particularly difficult for Drew. Harvard only accepted a handful of students of color each year, and most African American students had to apply to specifically African American institutions. Though Drew was accepted into Harvard, they asked that he defer until the following year. Instead, not wanting to have to wait the year, Drew applied and was accepted to the McGill University Faculty of Medicine in Montréal, where he excelled as a student. He graduated second in his class in 1933.[5]

Blood Bank Research

Drew began his two-year residency at Montreal Hospital in 1933, during which he worked closely with Professor John Beattie. At the time, Professor Beattie was working on using fluid replacement to treat patients with shock. Drew, having been particularly interested in this work, hoped to continue to study transfusions at the Mayo Clinic. However, as many white patients at the time would refuse to be treated by black healthcare professionals, large medical centers such as the Mayo tended not to hire black residents. Instead, Drew became a pathology instructor at the Howard University College of Medicine. He soon became a surgical instructor, before becoming chief surgical resident at the Howard University hospital (then known as Freedmen’s Hospital).[6]

Drew later began studying for a doctorate degree in medical science at Columbia University. Whilst there, he gained the opportunity to train under renowned surgeon Allen Whipple at Presbyterian Hospital in New York. Instead of allowing Drew to train with the other (white) residents, Whipple assigned Drew to work with Dr. John Scudder, who specialized in the research of shock, transfusions, and blood preservation, and was in the early stages of setting up an experimental blood bank.[7] Scudder quickly learned that Drew was gifted. He called Drew’s thesis, Banked Blood: A Study in Blood Preservation, “a masterpiece,” arguing that it was, “one of the most distinguished essays ever written, both in form and content.”[8] Drew was awarded his doctorate degree in medical science from Columbia in 1940, making him the first ever African American to earn a medical science doctorate from the university.

Blood for Britain

In 1940, with thousands injured in the second World War, the British government contacted the Red Cross in New York asking for blood and plasma (the liquid part of blood) to treat their casualties.[9] Upon receiving the bags of plasma, the British reported that the plasma appeared cloudy, rather than the clear yellow it was supposed to be. It was then that Dr. Drew was brought in to direct the Blood for Britain project. Though others had established basic methods for collecting and storing blood and plasma, it was Dr. Drew that implemented strategies to ensure that the quality of the blood collected was maintained before it could be administered to patients in need of a transfusion. His work allowed thousands to receive successful transfusions and saved thousands of lives.

Advocacy

Following the success of the Blood for Britain project, the National Research Council and the American Red Cross jointly commissioned a national blood bank, and Dr. Drew was invited to be the assistant director of the project. At the time, the Red Cross refused blood donations from African Americans. Though this rule was later rescinded, they still required the donations of African Americans to be labelled and stored separately from those of White people, so that they would only be used in transfusions for patients of each respective color. Dr. Drew was open in his criticism of the practice, stating that it was both “unscientific and insulting to African Americans.”[10]

Eventually, this led Dr. Drew to leave the Red Cross and return to Howard University where he became chair of the Department of Surgery and Chief of Surgery at the university hospital. There, Dr. Drew advocated for and mentored medical students and residents before later becoming the first African American examiner for the American Board of Surgery, the independent organization responsible for certifying surgeons as they complete their training. He also campaigned for black healthcare professionals to be granted memberships for medical institutions and organizations such as the American Medical Association (AMA). Drew himself died without ever being allowed membership in the AMA, despite his vast and lasting contributions to medical science.

Legacy

Dr. Charles Drew died as the result of a tragic accident, in which he fell asleep at the wheel whilst driving to a conference. He was only forty-five years old. Despite his premature death, Dr. Drew’s life’s work shaped a significant element of medical science. The way that blood banking and transfusions are carried out even today, would not be the same without Dr. Charles Richard Drew.

[1] National Library of Medicine. Charles R. Drew: Biographical Overview [Online] Available https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/spotlight/bg/feature/biographical. 2025.

[2] Ibid.

[3] American Chemical Society. Charles Richard Drew [Online] Available https://www.acs.org/education/whatischemistry/african-americans-in-sciences/charles-richard-drew.html. 2025.

[4] NLM, 2025.

[5] Ibid.

[6] ACS, 2025.

[7] Ibid.

[8] ii.

[9] New York-Presbyterian Hospital. Meet Dr. Charles Drew, pioneer in blood banking [Online] Available https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zx_ZCp8_ibs. 2019.

[10] NLM, 2025.

Page created on 3/17/2025 12:21:14 PM

Last edited 3/17/2025 12:28:16 PM