|

| (www.nytimes.com/2005/05/08/magazine/08EMIR.html) |

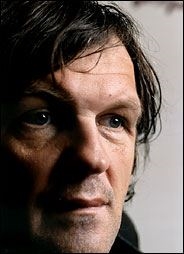

Twice the winner of Canne’s Palme d'Or, Emir Kusturica is an acclaimed director but a pariah in his home town, a man who was disillusioned after his childhood country was torn apart before his eyes but nonetheless uncompromisingly insists on telling its story. A strong and outspoken public presence, Kusturica has shown himself to be a man of principle and an artist with integrity.

His City in Flames

“Everything was somehow much more intense there than any other place,” said Kusturica of the outskirts of Sarajevo, Bosnia, where he grew up. Kusturica loved his hometown, and when fighting began there in 1992, he wrote a fervent plea for Bosnia in the French newspaper Le Monde, entitled “Europe, my City in Flames!” in which he stated that “the confrontation of Bosnian Muslims and the Bosnian Serbs is not authentic, it is a fabricated one, it developed on the rubble of fallen empires that left ashes behind. It is maintained by mindless nationalist movements.” Taking the route of many intellectuals, he refused to take sides in the conflict at its onset, instead expressing disapproval at the beginning of the separation of Yugoslavia.

However, he could not remain impartial after the new Bosnian Muslim authorities harassed his parents and militiamen raided their home, taking many valuables, including Emir’s film awards. He intervened, finding his parents an apartment to rent in Herceg Novi, Montenegro. In less than six months, his father died of a heart attack, which was accredited to the stress he had suffered upon having to leave his home. Kusturica is quoted as having said that it was the “spirit of intolerance” that caused the premature death of his father and has since likened it to the death of Yugoslavia on numerous occasions. "This war killed him, too," he said in an interview with New York Times. "My father got hit by invisible lightning. I compare the death of my father and the death of the country.”

Following his father’s death, his opinions of Bosnia changed drastically; angered by the intolerance of the new government that he saw as ruining the “multi-cultural essence” of Sarajevo, which he had helped built an image of through his earlier films. He did not hide his suffering at the break-up of his Yugoslavia, at first trying to defend it, then turning to Serbia as the most diverse of the newly founded nations, hoping it would “function as a substitute for the tolerant, vivid and multi-cultural Yugoslavia,” according to his biography by Dr. Dina Iordanova, word cinema specialist at the University of St. Andrews. He moved to it’s capital, Belgrade, disheartened that his childhood illusion of peace and belonging had been taken away. However, these events created an important foundation and frame for his future artistic endeavors.

|

| (www.kustu.com) |

Underground

Kusturica’s work is known for it’s cultural insight, humanist nature, and rich imagery. One of his greatest films, Underground, stands as an exemplar. It is a historical allegory spanning fifty years that incorporates documentary footage from important moments in Yugoslav history that overlap with the lives of the film’s protagonists. A vision conceived by Kusturica and playwright Dušan Kovaèeviæ, it provides insight into the historical origin of the violence in the 1990’s through the use of metaphor and dark comedy.

A major component of the Kusturica’s identity as both an artist and a person stems from his drive to reconstruct the past in both horrible and nostalgic ways. Underground is very much representative of that. It addresses all of the members of his generation, because he realized he was not the only one who viewed the dissolution of the country in personal terms. The film is formally dedicated to “our fathers and their children,” a label that includes all who have lived under communism in Yugoslavia and would best understand his vision. This very personal relationship with what Yugoslavia represented and how it impacted the shape of his identity makes the film humanistic at heart and a product of the director’s nostalgia and frustration in the face of what had become of his country. He relates historical events down to the level of a few individuals in order to correct the collective memory imposed by communism, and expose the unrecognized parts that the government and all of the nations of Yugoslavia played throughout history that culminated in the dissolution of the diverse country that he loved and continues to love.

The Judges at Cannes were infatuated with Underground, hailing it as a great intellectual achievement and seeing within its complexities references to Plato’s cave, Dante’s descent into the circles of Hell, Hegel’s dialectics, and Jung’s collective unconscious, awarding it a Palme d’Or in the 1995 festival.

Moving Forward

Displaced, Emir Kusturica still identifies himself as Yugoslavian, a title that to him even now evokes unity and diversity. "I never wanted an independent Bosnia," he said in an interview, "I wanted Yugoslavia. That is my country." Despite everything, he still sees the Yugoslav nations as a type of extended family that he does not want to completely disconnect from. The diversity that he longed for is now embodied in his family. His wife, Maja, is half Bosnian Serb, a quarter Slovene and a quarter Croatian, making his two children Slovene-Croat-Bosnian-Muslim Serbs and microcosms of Yugoslavia.

In the same nostalgic spirit of finding that which has been lost, he has also purchased land on a hillside on Mt. Zlatibor, Serbia, in 2005 and has re-created a traditional ethnic village on it, to replace the city that he had lost. He said that he wanted " to preserve something, and also to build something new - to build something for people, not for a nation, with no borders and no prejudice," and in that spirit bought twenty-five abandoned houses and had them relocated to the village, which goes by many names, including Küstendorf and Drvengrad (wooden town). He has said that the village is the “best film [he] has ever made” and announced in December of 2007 the formation of the Küstendorf Film Festival, an anti-commercial festival that celebrates student films and awards the winner a “golden egg”.

|

| Kusturica's village of Küstendorf (www.kustendorf.com) |

My Hero

Emir Kusturica is my hero because he is a man who was able to take his personal pain and the pain of his country and turn it into art that enlightens the mind and enlivens the spirit. I admire his work’s prominent and reoccurring theme of brotherhood that crosses the borders dividing both time and nations. He has a cautious optimism for a peaceful future, insisting, “there is still an energy in these people. They away never really know what has happened to them. That is the way of the Balkan people. They never rationalize their past. Somehow the passion that leads them forward is not changed. I hope some day people may find better ways to use the passion they have so far persistently used to kill one another.”

* Emir Kusturica’s most recent accomplishments include Maradona by Kusturica, a film about the life of one of his own childhood heroes, Argentinean footballer Diego Maradona.

Page created on 5/22/2009 10:30:54 AM

Last edited 5/22/2009 10:30:54 AM