|

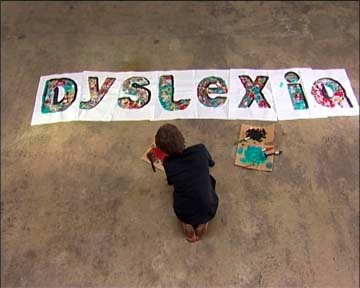

| Decoding Dyslexia (http://images.tvnz.co.nz/.../decoding_dyslexia/) |

Introduction

This is the story of three classrooms. The people in these classrooms contributed in different ways to my experience, faith and hope as someone with dyslexia and what would probably be known as ADD today. It is not a “how-to” missive on raising a creative learner, but I do hope it will give readers a macro-view of my experience and that, in doing so, the readers will be able to glean some relevant information, guidance and maybe comfort as they find their way through their own dyslexic labyrinth.

Part 1: The School Classroom

I‘ve never been big on following instructions. When they’re written they are a last resort and when they’re delivered by an authority figure, no matter how gentle the delivery, orders grate like a drill sergeant and are subjected to the eye roll of a skeptic. Even when it came to the sports I excelled in, a domineering coach would make me clinch.

I did well in ninth grade football because our coach was a very feminine man who would march us to a NYC park practice field swinging his scarf like a long string of pearls singing the Archie’s hit, “Oh sugar, oh honey, honey, you are my candy girl…,” which pretty much reflected his “Get Tough” coaching style. On the other hand, my first and last ski lesson lasted ten minutes. After I’d totally “mastered” the snow plow and tired of the instructor’s frustrated finger pointing to place the poles here and bend my knees there and move my head west when it naturally wanted to go east, and after I asked him “Mister, why can’t we just ski?” my weary ski-man winced with relief as I ditched the group and made my way down Stowe Mountain, plowing snow, a couple of trees and losing a ski. I never saw him again.

It didn’t stop there. A scout master wouldn’t admit me to the Boy Scouts of America because he might have intuited that I’d resist straight line formations in favor of dropping M-80s during the 4th of July parade.

I’m sure my resistance to directed activities came in part from the classroom. As a dyslexic, I found it hard to read and follow instructions. Test taking was a nightmare. If it was one of those fill-in-the-dots, #2 pencil tests, I would last about five minutes and then choreograph connect-the-dot patterns. Magically and perhaps realistically, I actually believed that an artistic filling in of the blanks would spin off more points than struggling through the material. When the clock began to run out, I’d resort to the widely accepted “Eeny, Meany, Miney, Mo” system. Naturally, my test scores were so low my mother was once warned by a sympathetic school admission’s officer that I might actually be “retarded.”

The hierarchical classrooms that I was raised in from grades 1-9 were designed for teaching us how to color in the lines, follow the rules, regulations and parameters, and memorize information and regurgitate all at a rigidly set pace. Since even when I did follow directions I didn’t seem to do well, what was the point? So instead of following directions, I would make my presence known in practical jokes, wise cracks and occasional punches that led to classroom quarantines and the principal’s office.

|

| In the Classroom (http://www.st-johns.org.uk/prospectus/classroom.jpg) |

Now my formal education was important to my parents. As the last of six children when my twin brother, Sam, and I were born, my dad was heard to exclaim with some panic, “How am I going to send them all to college?!” They had experienced how education had enriched their lives professionally, intellectually, culturally and socially. And naturally they wanted to pass this wealth on to their sons and daughters.

Nevertheless, they were gentle with me and my lousy school performance. When report cards came in, my dad would meet with me in his office and go through the grades and ask, “Well, I see you have a C- in English, what do you think you could do to pull it up to a C?” And my mom was no slouch when it came to downplaying low test scores and pointing out other gifts I might be harboring. But even here I revolted.

During summer vacations we were required to read a book a week and write a book report on it. My dad would review the book reports and affix affirming gold stars in the upper right-hand corner. One week I just couldn’t do it. Didn’t want to do it and, as I recall, a night before the deadline, there was a must see episode of Bonanza. I think it was something about Hoss and some nasty elves. Anyway, my parents were out for the evening which meant we could sneak a peek at the forbidden fruit referred to as the “idiot box.” I took Sam’s book report, copied it verbatim and handed it into my dad. I don’t remember what I was thinking. But I do remember I was grounded for two weeks, including the day on which my birthday fell. The message was clear from him. And in my message was I had had enough.

So while the structure of a traditional classroom setting, even with the support of tutors, shrinks and parents was not a place where I could make my kudos, I did have two other classrooms: the classroom of my immediate family and the classroom of imaginative play with my friends and by myself.

Part 2: The Classroom of Imaginative Play

About a week after Halloween I was in the grocery store. I saw a father shopping with his two children. They were still dressed up in their Halloween costumes. The boy was Superman and the girl was a fairy princess.

The boy was swooping through the aisles and the girl was pointing her wand at different items on the shelves transforming them into figments of her imagination. I liked the idea of this. Unlike a lot of parents I know, it didn’t seem to faze the father that his wee ones were still costumed and in character days after Halloween was over. He was letting them go on with their roles.

It also reminded me of my own childhood.

The curriculum of my imaginative play classroom took place indoors and outdoors; it was based on unstructured time, and my real and imaginary friends were my teachers.

By today’s standards of structured play, when it came to raising children, my upbringing was laissez faire. Whether we lived in New York City or a North Chicago suburb, the rules were pretty much the same. The first rule was to get outside and run off some of that energy, and the second rule was to be home by dinner time or by dark, whichever came first.

My parents didn’t seem to think it was much of their business what we were doing on the streets or the playground of Central Park. And except in heavy rain, all of us were sent out of the house to “play,” which, in those days, meant doing anything we felt like doing for as long as we felt like doing it.

We would go down our apartment elevator standing on the tiptoes of expectation. Spilling out of the elevator we’d play hide and seek up and down the alleyways of 91st and 92nd Street.

With a Jules Verne rolling around in our mind's eye, we dug a hole in Sheep’s Meadow to see what really was on the other side of the world, disappointed to find nothing but dirt and glass shards.

We would make an air force of paper airplanes with legal pads from my dad’s desk and toss them out our 16th story window watching them glide into the garden of MOMA, all the while creating in our minds new aerodynamic wonders. No matter we were starting at 200 feet in the air.

|

| Kids Playing in Central Park Photo by Martha Holmes Life Magazine (http://www.life.com/Life/) |

We formed exclusive clubs. These clubs came with special initiations. One was the common index finger cut and placed finger to finger with another, or secret passwords and secret handshakes, and once we even had to touch tongues. We practiced “tough love” among ourselves that could involve anything from ostracism, a punch in the arm (anything below the belt or above the neck was cheating), to the ridicule of a nickname: Latent Lad, John Conceited, Big Buns, Mountain Top, Mole Neck and so on. Telling on someone was, of course, completely and utterly out of the question and unforgivable.

On our newly invented and wobbly skateboards we were the Beach Boys incarnate as we were dragged behind buses down 5th Aveune. Our herd of Sting Ray Bicycles grouped into a formidable, albeit mini-me revs of the Hells Angels, with our tight pants and hood boots and lit punks hanging out of our mouths. We were, in our mind's eye, bad to the bone.

When that got boring, we pretended to be fighter pilots, spies and characters from movies and comic books.

We made up plays and formed rock groups modeled after the Beatles and tried to charge admission, but nobody would pay since our guitars were made of tennis racquets. We even had Terry Greenblatt film our band on Super 8, sure that when fame and fortune struck it would be featured in a theater near you.

In winter, hands red and wet, noses running, we dragged our sleds for blocks looking for the most dangerous hills doing imitations of derby drivers crashing into each other leaving us breathless in the piles of snow.

In the spring, we’d play a form of baseball against the side of the Jewish Museum using its perfectly curved wall to send a ball soaring through the obstacles of parked and oncoming cars. To us, we were in Yankee Stadium. The headless broom we used was a Louisville Slugger, and a dead tennis ball, a Mickey Mantle signature hard-ball. The smallest child, Ricky, was forced to play catcher, a brutal job often involving being clocked by the broomstick. When we got mad or lost the ball we’d quit and do something else.

Contrary to what the grown-ups said money did grow on trees and all the new leaves in the park became legal tender for the buying and selling of cans, rocks and tinfoil gum wrappers.

Those of us who had older brothers and sisters had encyclopedic knowledge of how babies were made and the slang words that were used for describing sex and body parts. If we didn’t know something, we’d ask the older kids. They were the professors. They told us dirty jokes and when they thought we had enough they’d send us away with a “Now git.”

We tried a criminal life shoplifting one bag after another of M&M peanuts until the Gristede’s butcher busted us and threatened to call our parents. We were instantly scared straight.

Then we’d test our manhood by seeing who could pee furthest across the street.

And when it rained I had my blocks and my soldiers. Built from one end of my room to the other and architecturally detailed, war between the blue and grey collapsed into an Armageddon of rubble and the lone survivor was my invisible friend and hero, Lancaster Grant. The front hall of my parent’s apartment became Madison Square Garden for which the Javits in the apartment below complained mightily. We’d build forts out of pillows and blankets and play war games. We were soldiers fighting in faraway lands.

Broomsticks to baseball bats, leaves to money, “old-school” skateboards to big wave surfboards, tennis racquets to guitar gods, bicycles to Harley Davidsons and legal pads to an air force. The point is that this kind of “freeD" play was all about emotional IQ. It allowed us to explore and role play and test our metal, raise and lower our self-esteem and experiment with teamwork. It allowed natural leaders to emerge, taught us consensus building and forgiveness, compassion, honesty, loyalty and so on. These were “skills” that couldn’t have possibly been taught to me in the classroom or under the coach-full eye of an adult.

Part 3: The Classroom of The Home

When I was nine years old we formed a rock band with real instruments called “What?” I remember going to the dentist’s office and, an apparently kind man, the dentist asked me about my interests. I told him I had a rock band called “What?” and that we’d be on Ed Sullivan pretty soon, so he should keep a look out. Now that wasn’t braggadocio, I really believed it. You see, free time gave me some skills I could not or would not learn in the classroom. My home life gave me visions that I could transform into a reality that was my own.

In the classroom of the home there were two lessons we were taught:

1. You can manifest your dreams, visions or ideas.2. It is okay to step outside the collective.

Before I elaborate, let me say that I believe that this is a touchy subject, touchy because we enter the realm of discussion about the role of nature versus nurture in human development.

The nature school believes that everything you are is determined by your genetic pool. Ever since I read about the nature school in college I've been uncomfortable with it.

Think about the implications for education or our potential to live our own lives as we are called to do so. We may have descended from a family tree that was known for its financial genius. Or a family with a history of engineering innovations. Or a history of so-called learning disabilities. Whatever our genetic heritage may say we will become, this school of thought projects that, no matter what, we are DNA.

Arthur Compton, in a series of lectures entitled "The Freedom of Man," began this series of lectures with the following paragraph:

The fundamental question …a subject of active investigation in science: Is man a free agent? If our actions are the necessary outcome of our past history, if the atoms of our bodies follow physical laws as immutable as the motions of the planets, why try? What difference can it make how great the effort if our actions are already determined by mechanical laws of cause and effect?

In other words, if everything acts according to definite and unchangeable laws, then why bother trying to be an artist when the DNA reads engineer?

Of course, Compton concludes that, indeed, human beings are free agents and the choices we make are real choices that are not necessarily the result of biologically inherited factors.

The second school is called the nurture school. They believe that you are born a tabla-rosa, a blank slate. In other words, our environment determines everything that you are. For example, if someone is brought up in a home where there is a lot of creativity, then one is likely to become more creative in their outlook, behavior and even their career choices. Likewise, the opposite is true. If a person is born and raised in a home where there is little stimulation and/or an emphasis on conforming to the expectations of the collective, tribe or societal norms, chances are that person will have a life that is characterized, at least from an outsider’s perspective, as “conservative,” normal,” “predictable."

But even this belief can create a sort of fatalistic determinism.

We might say to ourselves that we can't be creative because we were brought up in a home that emphasized the three R's, keeping your room clean, being practical in career pursuits, preparing yourself to pursue the material of the American Dream.

Therefore, I share the story of my home classroom with some reluctance. I believe in the power of the spirit. In other words, “the wind will blow where it wills” and while nature and nurture have some say in what we are and what we become, they don’t have the final say.

Having said that, I learned a great deal from my home. It’s not surprising since I had seven teachers.

|

| Dreams Photo courtesy of Jim Dean |

Lesson #1: Manifesting Visions

I didn’t know how important my ability to “dream” or envision the future was to me until, in a dark period of my life as an adult, I lost it.

Let me explain. When I was active in my alcoholism, as most of us alcoholics do, I hit the proverbial bottom. My bottom, the hole out of which I didn’t think I could climb, but desperately wanted to get out of, was the fact that I had lost my vision, my dreams, and my aspirations for a future. They say when you hit bottom, you are in a place of spiritual and moral bankruptcy. While my moral life was turbulent, it was my spiritual life that looked like a landscape by the Terminator.

You see, a major constituent of my spiritual life, the fuel of my life, the juice that woke me with an enthusiastic step in the morning, was that I had always had a vision, a dream of where I was going, what I could contribute to humanity, the community and the world, an idea that somehow was going to propel me to another stage of professional or personal growth. At the depths I had fallen to, my visions and dreams faded from view until I almost literally could not get out of bed.

I‘m convinced that it was my dreams and visions that fueled my way through many of the challenges of my life. My dreams and visions, no matter how improbable, were the light at the end of the tunnel. And when my drinking was in full swing, that light at the end of the tunnel was an oncoming Amtrak.

As someone who could not read a STOP sign and who was relegated to the back of the classroom with my crayons and drawing papers, dreaming big dreams was the only real skill I had worthy of calling a skill. Whether I told my parents I wanted to start a school in Jamaica for poor people, in spite of the fact that I was a poor student, or become an artist, in spite of the fact I had no eye-hand coordination, or be a rock star even though I had a tin ear, I don’t remember them ever dousing my visions with a “Get real” attitude.

Today, looking back at my life I can say I have been blessed with whatever I envisioned myself to be. Except perhaps a rock star.

When I was in advertising, I wanted my own agency and at 26 I started one. When I was 32 I wanted to be a minister and by the time I was 35 I was the Senior Pastor of a church. When I was 46 I want wanted to be an artist and, lo and behold, I had my first show by the time I was 47. At the same time I wanted to teach and I was blessed with a position teaching art and drama. When I was 50 I wanted to write a column for a paper and sure enough I am writing a column for two papers. I wanted to help young people who were battling the disease of drug and alcohol addiction and now I am in the process of opening a home for 20 adolescents in recovery. The point is, whether it was advertising or Yale Divinity School, art or counseling, writing or teaching, my dyslexia did not stand in the way of my career choices and the richness of the professional life I enjoy today. I was never allowed to think of it as a disability or as a reason not to do something I wanted to do.

How did this vision “thing” happen?

My mom wrote a book that was a collection of love letters between my dad and her entitled, Love Between Us. And in that book you can see they were dreamers. They had a vision for how they wanted their lives to unfold. Now, to be sure, they had gone through the Depression and a world war which certainly affected their need for security and a desire for a degree of predictability in their lives, but mostly they saw a home life that nurtured their creative well-being as well as the creative instincts of their children.

Although there were six of us scrambling around their home, they never resorted to a TV set for a babysitter. In fact, it was forbidden. It was no accident that it was called the “idiot box,” the “boob tube” and the “brain drain.” My dad, an advertising executive who had risen from the ranks of copywriter, would use vacations and weekends to paint and photograph as well as write in his journal. When he “retired” he immersed himself in full-time work as an artist.

My mother, between burning the beans and shaping meatloaves, patching knees and wounded feelings, would sit for hours at her Underwood pecking away reams of descriptive letters to her faraway mother, wrapping her arms around the chapter of her next book, taking writing classes at Columbia University and writing poems to accompany the quadrillion birthday gifts and Christmas presents she had to process every year. She had a song for every occasion…if we were late for school, she would sing “We’re late, we’re late it’s half past eight…” Or if my dad was late coming home from work, she would sing a ditty she composed about Alexander Graham Bell …and if we were naughty, she sang a song about “two little boys who flew out the door, flew right down to the grocery store and pooped on the vegetables, pooped on the ham and didn’t give a damn for the grocery man.” And we’d beg her to sing a provocative number from her theater days, a line of which was “It was one little apple that made Eve modest…” And I remember car rides where she would sing and we would groan…but be secretly enchanted.

With six children to track and recognize, it was not surprising that with the last name “Harper” performance and show and tell of the creative works and days of our hands and voices, writer’s pens, guitar and violin strings, stage rehearsals and so on were applauded and congratulated. These stand-up performances would bring me into a moment of spotlight that felt warm and embracing.

My parents are great storytellers; a description of an incident at a dinner party or in the office or even a tale about one of the six of us was told with an actor’s flare and a writer’s embellishment. Weekly trips to the theater were recounted with emphasis on the qualities of great writing, of great writers, great performances by the likes of Henry Fonda or Marlon Brando and so on. Just as likely there would be scathing reviews of ill conceived plays written by out of touch playwrights who had cast actors who had no clue that they were on Broadway or off-off-off Broadway. Weekend days were spent exploring the galleries and museums of New York. My dad collected a lot of work and you could see in his eyes a piece of abstract work that would light up his imagination and appreciation for an unsung artist. He was the first to bring home primitive or primal pieces from exotic landings abroad admiring out loud the simple vision of some anonymous artist from a distant land.

In addition, they would frequently take us to the theater. While it introduced me to a number of wonderful playwrights, primarily I witnessed the ability of people to turn ideas into reality.

This part of the home classroom curriculum taught me that whatever I could dream of doing I could manifest. Whatever vision could come to my mind's eye, with hard work, the right intent, a sense of humor and an ability to play well with others, could appear on the horizon and then in the reality of the day. No vision, no matter how improbable, was ever discouraged or frowned at as being impractical.

It was a lesson that was not lost on my brothers and sisters. My twin brother Sam who today is a screenwriter, an older brother Billy, a photographer, composer of contemporary operas and professor of music, a sister Diana who is an Elder in a Christian commune in Alaska, a sister Jessica who is an actress, songwriter, singer and children’s book author, and a sister Lindsay who is a book illustrator and fine artist.

It was as if we all believed we could transfigure our lives to fit whatever vision came into our heads.

|

| The wind blows where it wills. . . Sedona, Arizona Photo courtesy of Jim Dean |

Lesson #2: Step Outside the Collective

While some might have seen my parents as having bought into the values and props of upper-middle class society, they were not entirely at home in that collective.

Their collection of artwork was not like any of the traditional landscapes that decorated the walls of other homes. My dad would join boards of non-profits but always seem to end up occupying the lonely Chairman seat. They would join the “right” clubs but I never witnessed them spending much time in them or frankly having much interest in them. They preferred reading groups to football games. They would do Christmas skits dressed in giant Japanese paper mache masks and kimonos presenting us with gifts. They called themselves the ”Odd Pair.” And my mom’s interest in seeing her children pursue their bliss outweighed any desire to see her children streamlined into the ivy leagues or corporate culture.

In this part of the home classroom I learned that it was okay to be different, an odd lesson to come from an upper-middle class family. But there it was.

Now it was okay to be different but, as my dad would say, “If you just want attention, walk down the street with a sock in your mouth.” It wasn’t enough to look different, you had to have some substance behind your difference.

That isn’t to say there wasn’t some hand wringing around some of our life choices. Like Jessica quitting a prestigious women’s college to join the Broadway cast of “Hair,“ or Sam leaving a regular beat for an industry pub to write screenplays, or Lindsay leaving the security of a teaching position to pursue her art in New York City, or Billy leaving college to become a composer of contemporary operas, or Diana leaving the security and familiarity of a small town in New Hampshire to help build a self-sustaining commune in the netherlands of Alaska, or me leaving a lucrative career in the advertising business to go to Yale Divinity School.

In other words, in the classroom of the home, we were encouraged to find our particular passion and pursue it with passion, even if this meant an occasional leap of faith.

Today if I was a parent of someone who was a creative learner, I would apply four parts of my experience to them.

1. If I could not find a school that embraced children that are creative or experiential learners, I would enlist all the accommodations that are available today to help creative learners with testing and I would be very gentle but firm in my evaluations of their school report cards and comments.2. I would find tutors or other support people who are willing to identify and work with the particular interests of their student.

3. I would give them free time, unstructured time each and every day to be with friends or themselves without immediate adult supervision.

4. I would not emphasize their different way of learning and being, but I would embrace it as it came up.

Most of all I would believe, no, I would know that the “wind blows where it wills” and the universe in all of its goodness will bring your child to the exact place in life where he will be a divine and authentic expression of who and what he is.

Page created on 2/16/2009 12:00:00 AM

Last edited 10/25/2019 9:03:05 PM