Reprinted with permission from The Christian Science Monitor

Unfamiliar scripts and primitive art don’t always resonate with Jordanians who view them as a legacy of foreign powers. But the words and drawings have found a new audience.

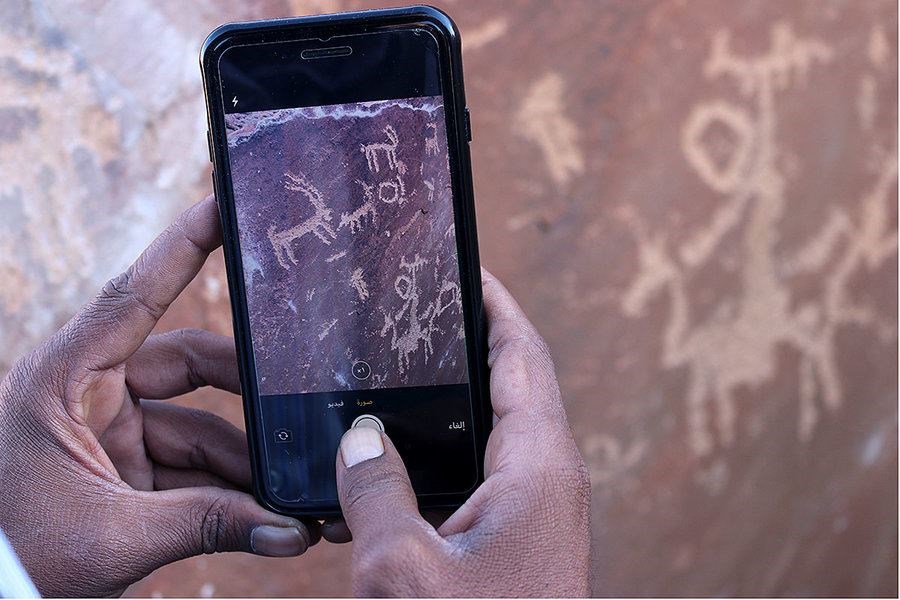

NOVEMBER 27, 2019 - WADI RUM, JORDAN - Mohammed Domian positions his mobile phone over the car-sized rock, peering at the carved outlines of a hunter, an ostrich, a lion, and an obscure line of text chiseled millennia ago.

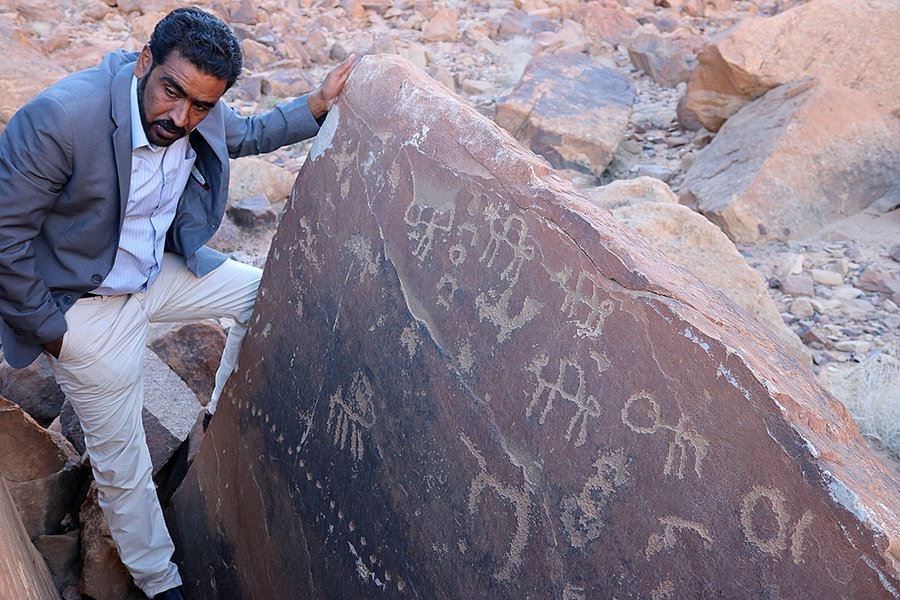

Mohammad Domian, Wadi Rum Protective Area official and lead rock art ranger, checks on 3,000-year-old Bedouin rock art, one of 45,000 examples of ancient inscriptions in the UNESCO World Heritage Site, November 19, 2019.Taylor Luck“‘Qamat son of Khalaf’,” Mr. Domian says, reading the script on his screen. “No change.”

Mohammad Domian, Wadi Rum Protective Area official and lead rock art ranger, checks on 3,000-year-old Bedouin rock art, one of 45,000 examples of ancient inscriptions in the UNESCO World Heritage Site, November 19, 2019.Taylor Luck“‘Qamat son of Khalaf’,” Mr. Domian says, reading the script on his screen. “No change.”

He clicks his phone. Upload sent.

This vast and still valley in southern Jordan that T.E. Lawrence called “echoing and god-like” cradles a sandstone sea of rock art: waves of carved camels, hunters, poems and other writings in alien-looking hieroglyphics and ancient Arabic splashed across cliffs, boulders, and cave walls.

Once you notice it, you see it everywhere.

Or you can also overlook the rough-hewn art, as many local Bedouins did for many years, dismissing its indecipherable scripts and primitive drawings as “meaningless.” Or, worse, disfigure the ancient inscriptions with graffiti “I was here.”

Those days are over. Today, Bedouins admonish anyone who tries to write on the rose-red rocks and alert managers of sites that are at risk of damage. Armed with smartphones and fired by cultural pride, they have become protectors of the past.

Wadi Rum – the desert valley in southern Jordan – is home to a sea of rock art and inscriptions stretching back several thousand years. Bedouin guides help protect the ancient works, November 19, 2019.Taylor Luck“Don’t touch or write on these inscriptions,” says elder Mohammed Al Howaity. “That would be insulting our ancestors and destroying our inheritance.”

Wadi Rum – the desert valley in southern Jordan – is home to a sea of rock art and inscriptions stretching back several thousand years. Bedouin guides help protect the ancient works, November 19, 2019.Taylor Luck“Don’t touch or write on these inscriptions,” says elder Mohammed Al Howaity. “That would be insulting our ancestors and destroying our inheritance.”

The carvings of Wadi Rum are as diverse as the history of these rugged sandy crossroads between Arabia, the Mediterranean, and North Africa.

Much of the art and inscriptions are in Thamudic, or Safaitic; the script, of Bedouin tribes who lived in northern Arabia over 3,000 years ago, a presumed precursor to Arabic and Aramaic.

Then came the Nabataeans, who built an empire from their third-century B.C. capital of Petra, and carved pictures and script in their own language that derived from Thamudic.

Cliff walls here also include messages and Koranic verses in Kufic – an early Arabic script. Then there are the primitive petroglyphs, stick men, women, animals and undecipherable symbols that predate all those civilizations by thousands of years.

These signposts of 12,000 years of continuous human desert life represent an evolution of human thought and language played out before your very eyes.

In 2011, UNESCO inscribed Wadi Rum as a World Heritage Site. It designated its 278 square miles as a mixed natural and cultural site of “outstanding universal value,” and said the inscriptions were “one of the world’s richest sources of documentation” of civilizations over millennia. To protect Wadi Rum, archaeologists adopted a Rock Art Stability Index to create an Arabic app-ready documentation tool and database of Rum’s rock art and inscriptions.

Mohammad Domian photographs rock art with a new documentation app in Wadi Rum, Jordan, on November 19, 2019. The supporting USAID program is designed to promote education, employment, and economic development in Jordan.Taylor LuckFor the past two years, Bedouin rock-art rangers have used their smartphones to document, photograph and measure over 12,500 pieces of rock art and inscriptions, supported by SCHEP (Sustainable Cultural Heritage Through Engagement of Local Communities Project), a USAID-funded organization for Jordanian cultural heritage.

Mohammad Domian photographs rock art with a new documentation app in Wadi Rum, Jordan, on November 19, 2019. The supporting USAID program is designed to promote education, employment, and economic development in Jordan.Taylor LuckFor the past two years, Bedouin rock-art rangers have used their smartphones to document, photograph and measure over 12,500 pieces of rock art and inscriptions, supported by SCHEP (Sustainable Cultural Heritage Through Engagement of Local Communities Project), a USAID-funded organization for Jordanian cultural heritage.

Rangers were taught to read and write the various symbols and scripts; a translation guide has been shared with local schools.

Project organizers brought scholars from Jordanian universities well-versed in Nabataean and Thamudic inscriptions to teach site staff and Bedouin rangers who can now read and write the various symbols and languages.

With the app, rangers are assigning a GPS location to each marking, tracking their current physical status, and listing near-term and long-term threats posed by humans, the environment, or tourism development. Experts say the valley holds as many as 45,000 inscriptions.

Mr. Domian, a site manager and lead rock ranger, has taught 25 Bedouin tour guides from Rum and the surrounding villages how to read and interpret the rock art. He and others have also tried to convince the community that the artworks are their cultural heritage, not a foreign imposition.

“There is a sense that in Jordan all these civilizations that passed through here were a series of foreign empires that came and went and had nothing to do with us,” says Nizar al Adarbeh, chief of party at USAID SCHEP, which is promoting a similar community-based approach to conservation at six other sites in Jordan.

“But it was our ancestors who built these monuments and cities, left behind art and poetry. The names of the empires may change, but it is the samepeople.”

All it takes is a little context and a few minutes over heavily-sugared tea with local residents to see how strong the links are to the past.

Most of the rock art shows ancient tribespeople hunting in a way very similar to that of today – with dogs, on a camel, using traps – and after prey such as rabbits.

Other inscriptions include devotions to religious deities such as the Nabataean god Allat and even Koranic verses. (Locals here, as in other rural communities in Jordan, write similar messages in Arabic on rocks, street walls, and highway signs.)

Some geometric shapes and lines are tribal symbols, signposts marking property to outside visitors; until the 1950s, a similar tradition was carried out by tribes here.

Rum’s ancient Bedouins also wrote on a subject that remains close to the hearts of young men and women: love.

“Most of these inscriptions are people’s names or declarations of love, just as young men today put a heart and their name next to their sweetheart’s,” says Mr. Domian.

“It shows that after all these thousands of years and after all this technology, things have not really changed at all.”

Bedouin guides and locals have also discovered that many of their Bedouin predecessors had names like Saleh, Omar, Ali, Saad, and Odeh, names that remain popular 2,000 years later.

The ancient art is a draw for tourists who number around 4,000 daily. Jazi al Manajaa has worked in the tourism industry for only a year but he already has a solid grasp on the importance of the inscriptions.

“The Thamudic era or the Nabataeans all lived a similar life to us today and left behind a guide to our shared way of life,” Mr. Manajaa says. “We have so much history to share with the world, not just our desert.”

Page created on 11/29/2019 8:32:05 PM

Last edited 11/29/2019 8:45:20 PM