REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION FROM THE CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR

On opening day for Major League Baseball, columnist Ken Makin looks at another side of Jackie Robinson’s legacy: statesman and writer.

Jackie Robinson holds a sign as he joins a picket line in Cleveland in 1960, to protest discrimination against Black people at Southern lunch counters.AP/File/File

Jackie Robinson holds a sign as he joins a picket line in Cleveland in 1960, to protest discrimination against Black people at Southern lunch counters.AP/File/File

When the U.S. Department of Defense removed Jackie Robinson’s history of military service from its website last week, there was one of Robinson’s professions I thought about even more than his careers as a baseball player and as a soldier.

I thought about Jackie Robinson the columnist.

Back in 1964, well after he played his last game and had been inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, Robinson trained his eyes on a presidential primary in Wisconsin. He was concerned that segregationist George Wallace, the infamous governor of Alabama, had secured close to a quarter of the vote in a Northern state. An excerpt from the April 25, 1964, column he wrote for the New York Amsterdam News was prescient not just in terms of the Defense Department’s actions, but also in terms of American democracy in general.

“This nation is in serious trouble. Too many of us fail to realize the depth of this trouble,” he wrote. “We are so certain of the strength of our democracy that those of us who really believe in it have become smug. We are concerned about the Castros and the Khrushchevs, the outsiders. We are not aware of the creeping corruption which threatens us from within.”

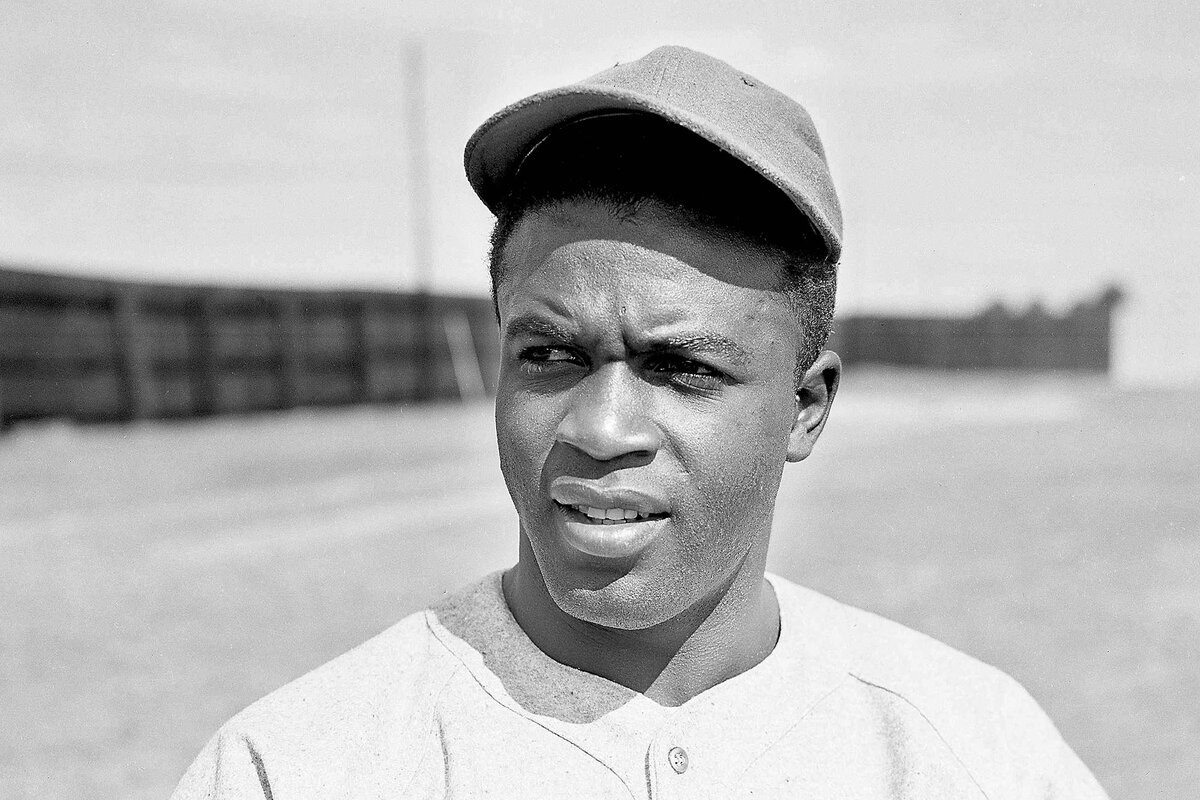

Bill Chaplis/AP/FileJackie Robinson plays with the Montreal Royals club, an international affiliate of the Brooklyn Dodgers, in Sanford, Florida, March 4, 1946.

Bill Chaplis/AP/FileJackie Robinson plays with the Montreal Royals club, an international affiliate of the Brooklyn Dodgers, in Sanford, Florida, March 4, 1946.

The Defense Department returned Mr. Robinson’s story to its website and reassigned the spokesman who had tried to justify its removal, but the damage was done. Attempting to separate Robinson’s baseball career from racial animus and conflict feels intellectually dishonest. He is largely recognized for breaking the color barrier in baseball, an achievement that goes beyond his baseball prowess.

The temporary attempt to separate sports from politics speaks to a greater and shortsighted divide. From the fervor surrounding Colin Kaepernick’s Black Lives Matter protests to Laura Ingraham’s controversial declaration to LeBron James, “Shut up and dribble,” notions that athletes should keep their personal views away from the field of play have been prevalent. And wrong.

Sports and politics have always been bedfellows, however controversial. Since their inception decades ago, the Olympics couldn’t help but ultimately be an exercise in geopolitics. Jesse Owens competed in Nazi Germany, his athletic prowess a rebuke of Hitler’s racial superiority agenda. And yet, the track and field athlete said he was treated better in Berlin than he was back in the States.

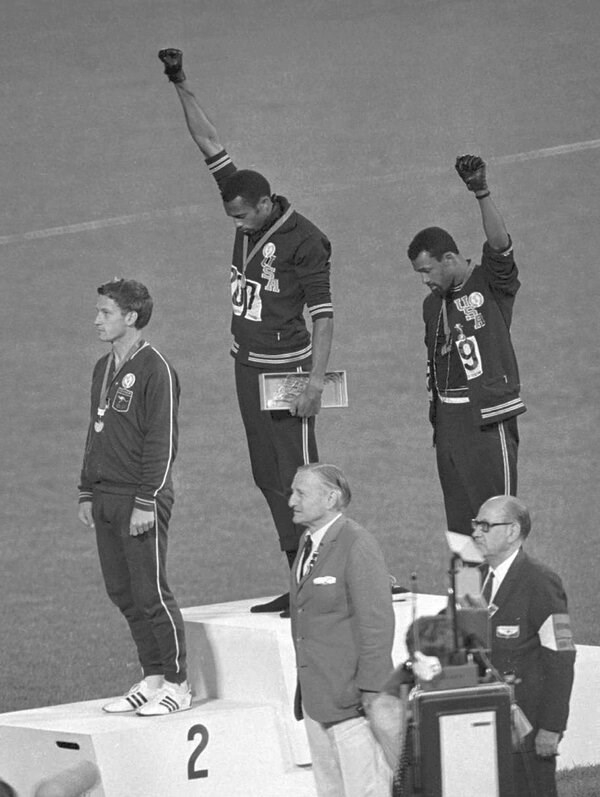

More than 30 years later, John Carlos and Tommie Smith threw up the Black Power fists seen all over the world. It was the climactic point of a protest that had originally been proposed as an outright boycott of the Olympic games.

AP/FileU.S. athletes Tommie Smith (center) and John Carlos extend gloved hands skyward in racial protest during the playing of "The Star-Spangled Banner" after Mr. Smith received the gold and Mr. Carlos the bronze for the 200-meter run at the Summer Olympic Games in Mexico City, Oct. 16, 1968.

AP/FileU.S. athletes Tommie Smith (center) and John Carlos extend gloved hands skyward in racial protest during the playing of "The Star-Spangled Banner" after Mr. Smith received the gold and Mr. Carlos the bronze for the 200-meter run at the Summer Olympic Games in Mexico City, Oct. 16, 1968.

Even distilling the separation of sports and politics down to Black and white doesn’t fully capture the insightfulness of the progressive and conscientious athlete. Chris Kluwe, a former NFL punter, said he was fired from coaching high school football after he protested a MAGA plaque, and was later arrested at a city council meeting.

This brings us back to Robinson, who is as palatable an activist in the modern day as the likes of Martin Luther King Jr. That is largely because of how U.S. society has minimized both men’s commentaries and legacies.

Robinson was a Republican, and not in the radical sense, like Robert Smalls of the 1860s Reconstruction era. Robinson famously endorsed Richard Nixon over John F. Kennedy in 1960 because he thought the former to be a better champion of civil rights. He also was on the floor at the GOP convention in 1964, witnessing the end of his hopes that civil rights victories could be won by having both major parties compete for Black voters.

“It was a crushing defeat for Robinson’s political worldview,” wrote Sidney Carlson White in an article titled “Jackie and the 1964 Republican National Convention.” “But by the middle of the decade, it became clear that the Republican Party had no interest in winning back the groups whose support had shifted. Though Robinson’s belief in the functionality of the two-party system was shaken, he continued to be civically engaged for the rest of his life, fighting to support the candidates he believed would join him in demanding racial and economic justice in the United States.”

The Defense Department’s actions have one silver lining – they allow us to celebrate and appreciate Robinson as more than a baseball player and a soldier. He was a statesman of the highest order, a man who understood the significance of his presence and, further, the power of his voice. His words ring so loudly in the face of racism and divisiveness that they resonate years after his passing, and most notably among actions to erase his legacy. And despite the deliberate disrespect he experienced throughout his life, Robinson still chose America, and had a message to those who were serious about protecting democracy.

“If we want to preserve America – the America that was to be in the minds of its founding fathers – we had better wake up,” Robinson wrote in that April 25, 1964, column.

Page created on 3/28/2025 4:07:25 PM

Last edited 3/28/2025 4:20:37 PM