Robert Shetterly

Robert Shetterly

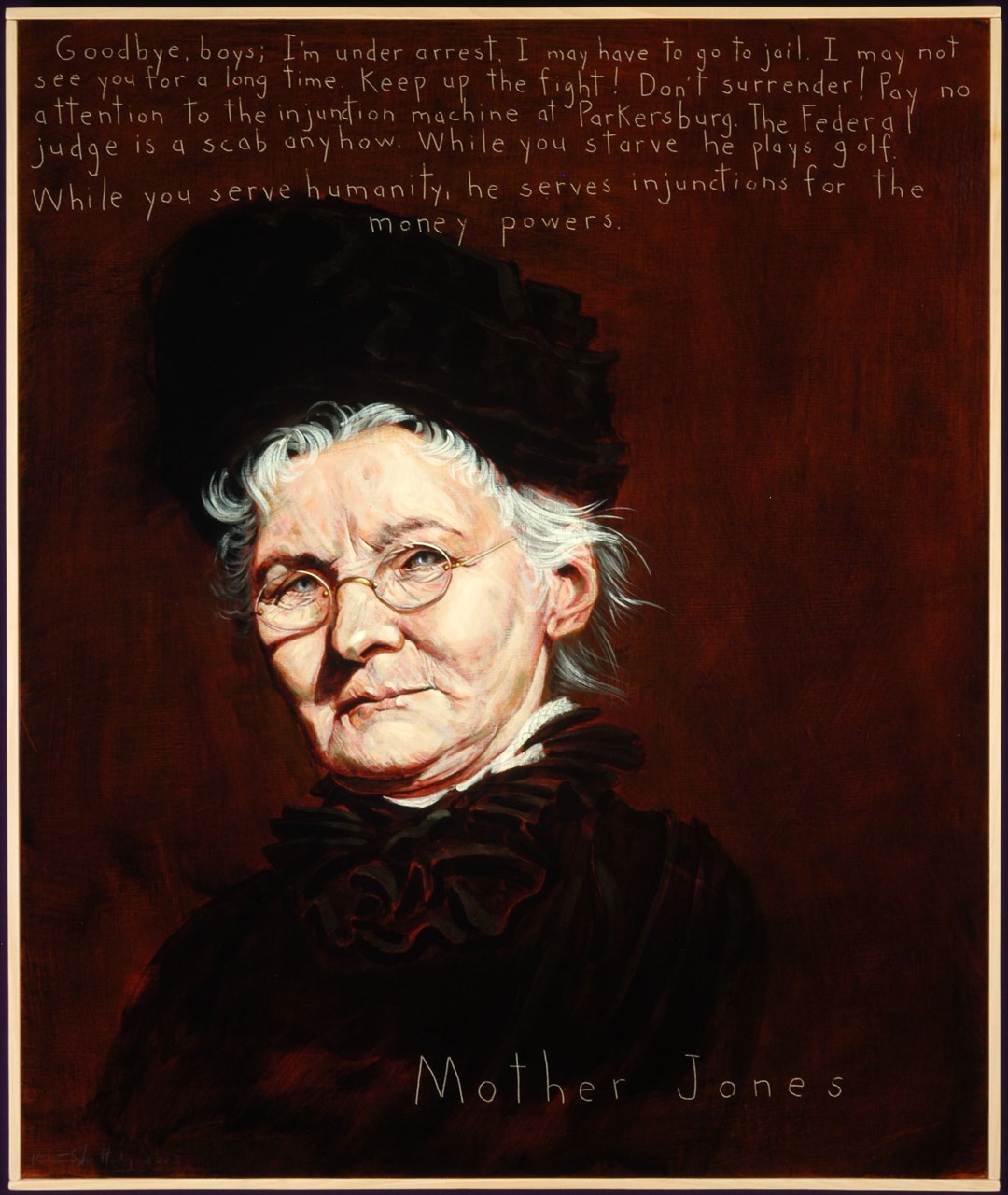

Mother Jones sat on the witness stand in court. She sat with her back straight, her white hair pulled into a bun. She wore an old, but proper, black gown with a high neck. She was on trial for subversive speech, but she did not appear frightened. When she smiled, the corners of her mouth drew back into plump cheeks, and like a wide-eyed infant, her gaze did not waver from fear or shame as the prosecutor pointed at her, declaring to all present that here before them was the "most dangerous woman in the country."

It was the time of the Industrial "Revolution" in America, when thousands of people were coming from Europe to take part in what they thought would be a place of freedom, where they could work for themselves and their families, and share in the wealth that they helped to create in the mines and railroads and factories. The owners of these industries took advantage of the waves of immigrants willing to work, and consequently the nineteenth century was the time of the 10- and 12-hour workday, the $3 a week wage, of children going to the cotton mills at the age of six to help supplement the father's meager income. It was a time when miners were paid in scrip, so that they had to pay their rent back to the company, buy their food and dry goods at the company store, and never had cash in case they wanted to leave and start over somewhere else. Here they were truly slaves until they died from illness brought on by overwork, or because of unsafe conditions, and had to be replaced by the next worker fresh off the boat, or even their own children.

When Mary Harris Jones was a young girl, her father had moved their family from Cork, Ireland, to the United States, where he worked as a laborer until his death. She herself worked as a school teacher and a dressmaker until her marriage. In 1867 she was living in Memphis, when her husband and four children died in a yellow fever epidemic. She was 37. Jones obtained a special permit to enter the quarantined houses, and stayed in the town nursing the sick and dying until the epidemic was over.

She moved to Chicago, opened a dressmaking shop with a partner, and began attended the meetings of the Knights of Labor evenings. Because she catered to the rich, she was acutely sensitive to the imbalance of wealth in Chicago society and Knights of Labor meetings taught her about the logistics of labor organizing. So when Jones' dress shop burned in the Chicago Fire of '71, she was not at a loss for something to do. She took up an activity that perfectly appealed to her talents and sense of the injustices all around her: she began agitating for labor. By 1880, she was 50 years old and "wholly engrossed in the labor movement."

For the next 50 years, Jones traveled around the country, speaking and organizing, and helping wherever she could. An honest and fearless leader, she was also impossible to intimidate. Many times she faced down a threatening remark or even the muzzle of a rifle with imperturbable wit. Her purpose was clear and she was never loath to state it: to free the men, women and children of the working class from what she called "industrial slavery," to save them from early sickness and untimely death, to save them from the misery of never having the leisure time to read a book or just sit and think, of never having the freedom to choose the course of their own lives.

Jones was thrown in jail many times for her activities. She had been arrested and brought into court for speaking to a group of miners about labor issues. This was possible because at the time, the mining company not only owned the place where its employees worked, but also the houses they lived in, the stores they shopped at, the roads they walked on to get to work, and the company had gotten a court injunction against talking about labor issues on its property. True to form, Jones ignored the injunction, and had gone ahead and said what was on her mind.

Jones had seen more of the goodness and evil of the human race than did most people, and this experience sharpened her, gave her knowledge to add to her own inborn wisdom. Jones dedicated half a century to gain basic rights for ordinary workers against their employers, the omnipotent and wealthy industrial giants. Before getting on the stand, Mother Jones had sworn on the Bible (she was deeply religious and swore with all her heart) to tell the truth. Yet, she didn't need a Bible or an oath to make her speak the truth. It was for this reason more than any other, perhaps, that the prosecuting attorney pointed at her and uttered his cowardly words.

At age 95, Mother Jones published her autobiography. It contains various anecdotes about her efforts to help workers from Virginia to Mexico, including a "tour" she took, accompanied by several young mill workers, to bring attention to the tragedy of child labor. The book itself is one of the most important, least self-aggrandizing memoirs ever written, and it's a fitting legacy for someone once called the most dangerous woman in the country.

Mary Harris Jones died in 1930 at age 100, and was buried in the Union Miner's Cemetery in Mount Olive, Ill. In 1936, her friends erected a monument there in her honor.

Page created on 5/1/2007 5:25:42 AM

Last edited 6/10/2020 6:40:19 AM