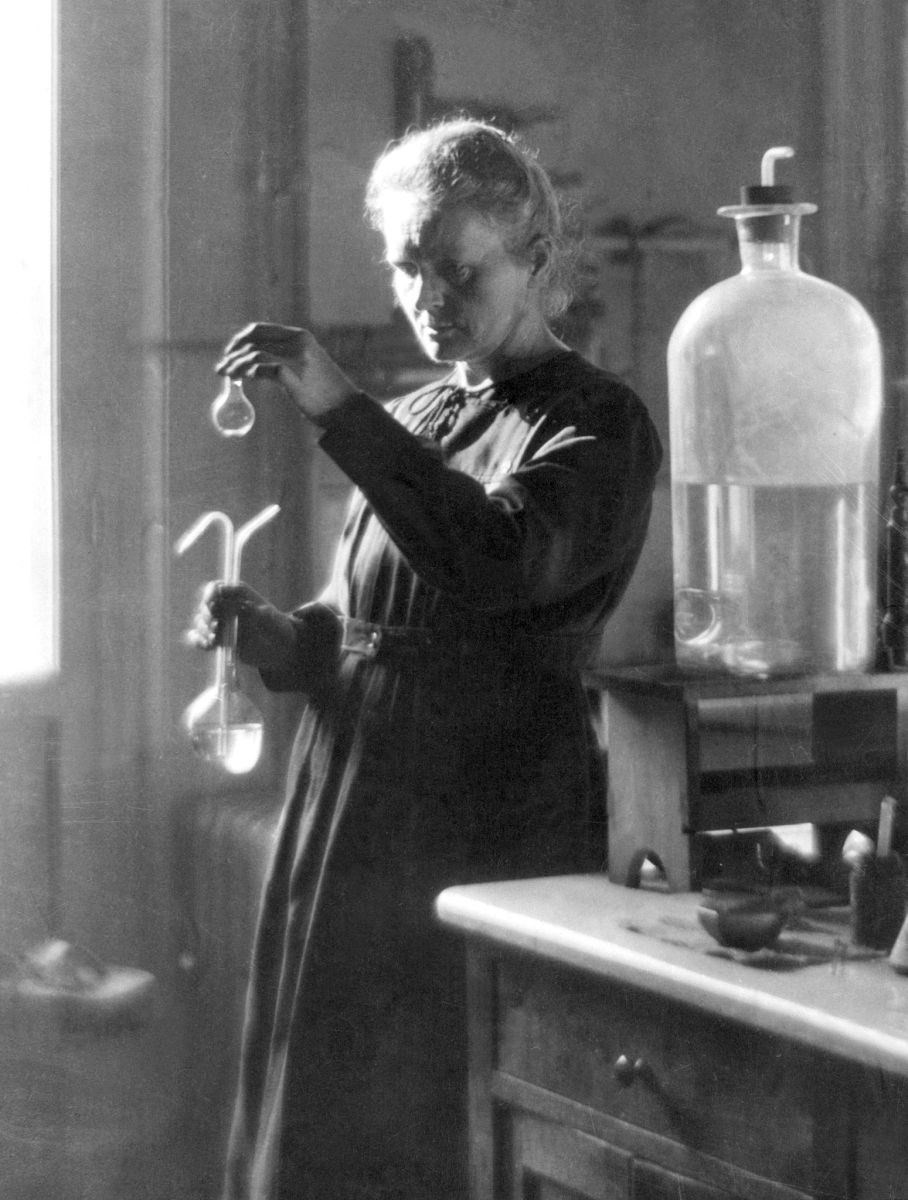

Marie Curie in her labhttps://www.biography.com/people/marie-curie-9263538Celebrities – actors, artists, and athletes – are considered to be the superheroes of modern society because of their wealth and not their virtues. In his article “Heroes on Our Doorstep” (1994), Mike Barnicle highlights society’s flaw: “We constantly confuse heroism with celebrity, figuring that because someone is famous or skilled at a specific task – carrying a football…– that they are mythic figures incapable of disappointing us with any of the evils committed by ordinary human beings” (Barnicle). If society regardlessly applauds celebrities, then who can we consider a hero? Heroes risk their own health and comforts to overcome difficulties without the intention of being recognized and admired. Heroism is demonstrated through everyday actions from everyday people: parents working multiple jobs to support their families, doctors saving lives and comforting patients, and teachers dedicating additional time after school to help struggling students. These heroic deeds inspire individuals of a community through accomplishments and service, but do not necessarily receive recognition from the entire society. However, people commended as widely recognized heroes accomplish more than impacting their families or communities. Heroism is not measured in terms of wealth; instead, modern society’s heroes should be people who apply their intelligence to conquer widespread obstacles.

Marie Curie in her labhttps://www.biography.com/people/marie-curie-9263538Celebrities – actors, artists, and athletes – are considered to be the superheroes of modern society because of their wealth and not their virtues. In his article “Heroes on Our Doorstep” (1994), Mike Barnicle highlights society’s flaw: “We constantly confuse heroism with celebrity, figuring that because someone is famous or skilled at a specific task – carrying a football…– that they are mythic figures incapable of disappointing us with any of the evils committed by ordinary human beings” (Barnicle). If society regardlessly applauds celebrities, then who can we consider a hero? Heroes risk their own health and comforts to overcome difficulties without the intention of being recognized and admired. Heroism is demonstrated through everyday actions from everyday people: parents working multiple jobs to support their families, doctors saving lives and comforting patients, and teachers dedicating additional time after school to help struggling students. These heroic deeds inspire individuals of a community through accomplishments and service, but do not necessarily receive recognition from the entire society. However, people commended as widely recognized heroes accomplish more than impacting their families or communities. Heroism is not measured in terms of wealth; instead, modern society’s heroes should be people who apply their intelligence to conquer widespread obstacles.

Curie in World War I - Radiological Unit Carhttps://www.weblessons.com/webcurrents.php?id=128A woman who studied in the Polish language (despite Russian laws that forbade it) attended university when women were precluded from studying. She discovered two obscure yet groundbreaking elements while working with meager equipment. This woman was Marie Curie and she exemplifies a true hero. Born into a poor family in Warsaw, Poland on November 7, 1867, Curie coped with several adversities to become the first woman to receive a Nobel Prize and the first ever to earn two of them. As a result of Russian law, she attended a private Polish school and surreptitiously enrolled in advanced science and Polish culture courses at the “Floating University.” Marie struggled to find a steady income to afford studying at the Sorbonne, a university in Paris, France. With her husband, Pierre Curie, she worked for years in a shed to discover polonium and radium, two essential radioactive elements. Corroborating the existence of radium earned the Curies a Nobel Prize in 1903. Despite being awarded considerable prize money for their discovery, the impoverished couple enjoyed a modest amount, dedicated some to their research, and donated the rest to others in need. In 1911, Marie Curie received her second Nobel Prize for introducing medical procedures involving radium such as cancer treatment and other healing. In World War I, Marie Curie contributed to France’s war with Germany by dedicating her research and radiologic technology to significantly improve soldier mortality rates. Throughout her life, Marie Curie ignored fame and valued her passion to learn. Even in her old age, she instructed at the Radium Institute to inspire and motivate brilliant and passionate students. Living as a pioneering chemist, Marie Curie demonstrated that heroism is a combination of determination, which means to continue working despite harsh conditions, and humility, which is to not brag about accomplishments or credentials. By persevering through impoverished and harsh working conditions, and developing a humble disinterest towards money and her own accomplishments, Marie Curie accentuated her capability to serve as an inspirational and heroic innovator.

Curie in World War I - Radiological Unit Carhttps://www.weblessons.com/webcurrents.php?id=128A woman who studied in the Polish language (despite Russian laws that forbade it) attended university when women were precluded from studying. She discovered two obscure yet groundbreaking elements while working with meager equipment. This woman was Marie Curie and she exemplifies a true hero. Born into a poor family in Warsaw, Poland on November 7, 1867, Curie coped with several adversities to become the first woman to receive a Nobel Prize and the first ever to earn two of them. As a result of Russian law, she attended a private Polish school and surreptitiously enrolled in advanced science and Polish culture courses at the “Floating University.” Marie struggled to find a steady income to afford studying at the Sorbonne, a university in Paris, France. With her husband, Pierre Curie, she worked for years in a shed to discover polonium and radium, two essential radioactive elements. Corroborating the existence of radium earned the Curies a Nobel Prize in 1903. Despite being awarded considerable prize money for their discovery, the impoverished couple enjoyed a modest amount, dedicated some to their research, and donated the rest to others in need. In 1911, Marie Curie received her second Nobel Prize for introducing medical procedures involving radium such as cancer treatment and other healing. In World War I, Marie Curie contributed to France’s war with Germany by dedicating her research and radiologic technology to significantly improve soldier mortality rates. Throughout her life, Marie Curie ignored fame and valued her passion to learn. Even in her old age, she instructed at the Radium Institute to inspire and motivate brilliant and passionate students. Living as a pioneering chemist, Marie Curie demonstrated that heroism is a combination of determination, which means to continue working despite harsh conditions, and humility, which is to not brag about accomplishments or credentials. By persevering through impoverished and harsh working conditions, and developing a humble disinterest towards money and her own accomplishments, Marie Curie accentuated her capability to serve as an inspirational and heroic innovator.

Even though she encountered several arduous and tedious obstacles, Marie Curie heroically persevered to accomplish phenomenal research. As portrayed by Curie’s daughter in her book Madame Curie A Biography (1937), Marie Curie’s transition to France caused struggles involving her studies: “Lights were at a minimum: as soon as night fell, the student took refuge in that blessed asylum called the Library of Sainte-Geneviève… [where] a poor Polish girl could work until they closed the doors at ten o’clock.… [S]he wrote figures and equations without noticing that her fingers were getting numb and her shoulders shaking.… For weeks at a time she ate nothing but buttered bread and tea” (E. Curie 108-109). Despite her poverty, highlighted by the fact that she could not even afford enough lighting, Marie Curie was determined to break the limitations of penury and persevered to study for hours while enduring small meals of “buttered bread and tea.” Eve Curie also uses the gloomy words, “minimum,” “refuge,” and “asylum” to illustrate the bleak atmosphere of Marie Curie’s strenuous nights of ceaseless studying while coping with poverty. Instead of taking care of her health, Marie Curie was determined to prove that she was capable of managing difficult tasks and adapting to harsh working conditions. Curie proved herself a hero by persevering beyond society’s expectations for women and by showing her potential for accomplishments. When she proceeded to research and benefit society, Curie encountered many of the same issues caused by poverty. Marie Curie demonstrated her persistence by conducting tedious research in deplorable conditions to isolate polonium and radium: “Marie describes the shed as having a bituminous floor, and a glass roof which provided incomplete protection against the rain, and where it was like a hothouse in the summer, draughty and cold in the winter… Wilhelm Ostwald, the highly respected German chemist… wrote: ‘It was a cross between a stable and a potato shed, and if I had not seen the worktable and items of chemical apparatus, I would have thought that I [had] been played a practical joke’” (Fröman). Despite daily fatigue and the lack of a proper laboratory, the poor scientist diligently dedicated several hours a day to working in the “potato shed.” By writing, “‘I would have thought that I [had] been played a practical joke,’” Ostwald depicts that Curie’s shed was deficient of proper laboratory conditions. Marie Curie coped with the inadequate equipment and spent significant time meticulously separating the pure radium and recording precise measurements by hand. Furthermore, Curie labored in an unprotected shed where the outside weather invaded the laboratory. These conditions exposed the studied material and made it vulnerable to contamination. Despite this, she managed to have accurate results because she worked conscientiously. Tenacity, perseverance, and diligence allowed Curie to expand the boundaries set by her physical and financial limitations and to apply radiology into other fields.

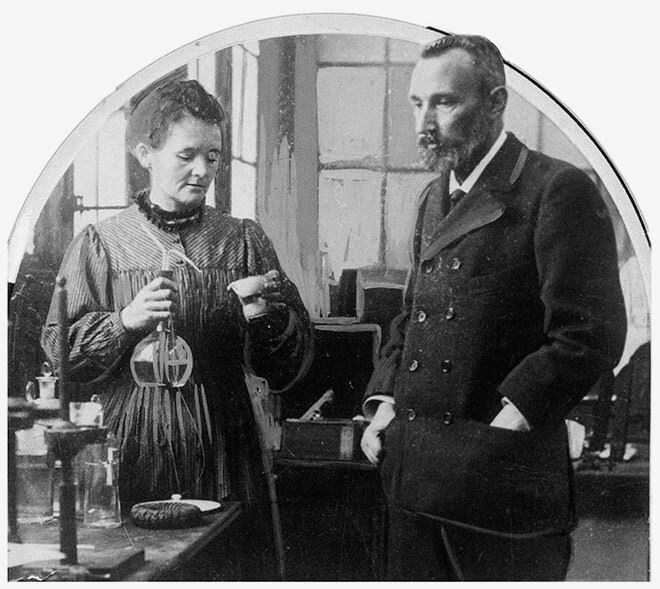

Marie Curie with her husbandhttps://www.pinterest.com/pin/571323902712691603/Rather than flaunting her groundbreaking discovery, Marie Curie remains humble and heroically detests wealth and recognition. Curie reflects on the years following her first Nobel Prize in 1903, and exhibits her aversion towards constant admiration: “Visitors and demands for lectures and articles interrupted every day.… The fatigue resulting from the effort exceeding our forces, imposed by the unsatisfactory conditions of our labor, was augmented by the invasion of publicity” (M. Curie). The couple was frequently disturbed by reporters, causing their research to become inefficient and their privacy to be invaded by fame. Despite pioneering in the study of radioactivity, Marie Curie preferred the life of a humble, unrecognized researcher. By explaining, “[t]he fatigue… was augmented by the invasion of publicity,” she emphasizes the negative impacts of fame: hindrance to their research and conflict with her humble values. Marie Curie heroically proceeds with her research, indifferent about her fans. She demonstrates that despite contributing to the world of knowledge, scientists should not strive to become celebrities. Along with interviews and requests for autographs, Marie Curie found large offers of money annoying, and had no regrets not capitalizing on her revolutionary discovery of radium: “‘…humanity also needs dreamers, for whom the disinterested development of an enterprise is so captivating that it becomes impossible for them to devote their care to their own material profit. Without the slightest doubt, these dreamers do not deserve wealth, because they do not desire it. Even so, a well-organized society should assure to such workers the efficient means of accomplishing their task, in a life freed from material care and freely consecrated to research’” (qtd. in E. Curie 336). Marie Curie states that she is a “dreamer” and a scientist dedicated to research, but not destined to be wealthy. Success for Curie is completing research that will have more benefit than simply earning an award. Rather than valuing the physical trophies and medals that they earned from their discovery of radium, Marie and Pierre humbly educated the public on the positive applications of their breakthrough and made no effort to financially profit or to acquire fame. Marie Curie heroically rejected the potential profits despite her years of painful work. Curie and her concentrated ardent desire to impact science allowed for no interest towards the pleasures and comforts of becoming a celebrity and profiting from her discoveries.

Marie Curie with her husbandhttps://www.pinterest.com/pin/571323902712691603/Rather than flaunting her groundbreaking discovery, Marie Curie remains humble and heroically detests wealth and recognition. Curie reflects on the years following her first Nobel Prize in 1903, and exhibits her aversion towards constant admiration: “Visitors and demands for lectures and articles interrupted every day.… The fatigue resulting from the effort exceeding our forces, imposed by the unsatisfactory conditions of our labor, was augmented by the invasion of publicity” (M. Curie). The couple was frequently disturbed by reporters, causing their research to become inefficient and their privacy to be invaded by fame. Despite pioneering in the study of radioactivity, Marie Curie preferred the life of a humble, unrecognized researcher. By explaining, “[t]he fatigue… was augmented by the invasion of publicity,” she emphasizes the negative impacts of fame: hindrance to their research and conflict with her humble values. Marie Curie heroically proceeds with her research, indifferent about her fans. She demonstrates that despite contributing to the world of knowledge, scientists should not strive to become celebrities. Along with interviews and requests for autographs, Marie Curie found large offers of money annoying, and had no regrets not capitalizing on her revolutionary discovery of radium: “‘…humanity also needs dreamers, for whom the disinterested development of an enterprise is so captivating that it becomes impossible for them to devote their care to their own material profit. Without the slightest doubt, these dreamers do not deserve wealth, because they do not desire it. Even so, a well-organized society should assure to such workers the efficient means of accomplishing their task, in a life freed from material care and freely consecrated to research’” (qtd. in E. Curie 336). Marie Curie states that she is a “dreamer” and a scientist dedicated to research, but not destined to be wealthy. Success for Curie is completing research that will have more benefit than simply earning an award. Rather than valuing the physical trophies and medals that they earned from their discovery of radium, Marie and Pierre humbly educated the public on the positive applications of their breakthrough and made no effort to financially profit or to acquire fame. Marie Curie heroically rejected the potential profits despite her years of painful work. Curie and her concentrated ardent desire to impact science allowed for no interest towards the pleasures and comforts of becoming a celebrity and profiting from her discoveries.

Marie Curie with U.S. President Hooverhttps://www.american-presidents.org/2009/11/marie-curie-and-two-american-presidents.htmlMarie Curie distinguished herself from ordinary people and celebrities by persevering through poverty and despising admiration and fame. One of the key components to measure heroism is determination, which Marie Curie demonstrated throughout her poverty-stricken life, forcing her to work more diligently than her peers. This is especially significant because heroes strive and suffer extreme amounts in order to improve the lives of others. Marie Curie’s harsh toil in the dilapidated shed and her discovery of two revolutionary radioactive elements transformed medical science by assisting doctors and efficiently healing wounded soldiers. Furthermore, Marie Curie rejected wealth by not patenting her discovery, and improved scientists’ to access information. Additionally, Curie inspires others by demonstrating her modest views about herself: “Sweet Mé who, along the years, neglected completely to apprise us that she was not a mother like every other mother, not a professor crushed under daily tasks, but an exceptional human being, an illustrious woman” (E. Curie 273). By believing that she deserved no more acknowledgment than the average mother or professor, Marie Curie inspires others to remain humble even after extraordinary achievements. Receiving recognition for these discoveries did not affect her modesty; passion was always the driving force for Curie’s contribution to science. Her values inspire me to strive out of dedication instead of hoping for recognition. Marie Curie teaches me that impacting society and inspiring peers are far more valuable than a shelf decorated with prizes. She showed that trophies are meant to symbolize a potential for inspiring others. According to Mike Barnicle’s definition of a hero, Marie Curie represents one who modern society should idolize: one who constantly perseveres through life’s struggles, but does not work for fame.

Marie Curie with U.S. President Hooverhttps://www.american-presidents.org/2009/11/marie-curie-and-two-american-presidents.htmlMarie Curie distinguished herself from ordinary people and celebrities by persevering through poverty and despising admiration and fame. One of the key components to measure heroism is determination, which Marie Curie demonstrated throughout her poverty-stricken life, forcing her to work more diligently than her peers. This is especially significant because heroes strive and suffer extreme amounts in order to improve the lives of others. Marie Curie’s harsh toil in the dilapidated shed and her discovery of two revolutionary radioactive elements transformed medical science by assisting doctors and efficiently healing wounded soldiers. Furthermore, Marie Curie rejected wealth by not patenting her discovery, and improved scientists’ to access information. Additionally, Curie inspires others by demonstrating her modest views about herself: “Sweet Mé who, along the years, neglected completely to apprise us that she was not a mother like every other mother, not a professor crushed under daily tasks, but an exceptional human being, an illustrious woman” (E. Curie 273). By believing that she deserved no more acknowledgment than the average mother or professor, Marie Curie inspires others to remain humble even after extraordinary achievements. Receiving recognition for these discoveries did not affect her modesty; passion was always the driving force for Curie’s contribution to science. Her values inspire me to strive out of dedication instead of hoping for recognition. Marie Curie teaches me that impacting society and inspiring peers are far more valuable than a shelf decorated with prizes. She showed that trophies are meant to symbolize a potential for inspiring others. According to Mike Barnicle’s definition of a hero, Marie Curie represents one who modern society should idolize: one who constantly perseveres through life’s struggles, but does not work for fame.

Works Consulted

Barnicle, Mike. “Heroes on Our Doorstep.” HighBeam Research - Newspaper Archives and Journal Articles, The Boston Globe (Boston, MA), www.highbeam.com/doc/1P2-8284611.html.

Curie, Eve. Madame Curie: a Biography. Da Capo Press, 2001.

Marie Curie: Fame and Illness (In Her Own Words) - BRIEF Exhibit, history.aip.org/exhibits/curie/brief/06_quotes/quotes_10.html.

"Marie and Pierre Curie and the Discovery of Polonium and Radium". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2014. Web. 23 Jan 2018. <https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/themes/physics/curie/>

Page created on 2/15/2018 7:24:54 PM

Last edited 2/28/2018 5:29:34 PM