REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION FROM THE CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR

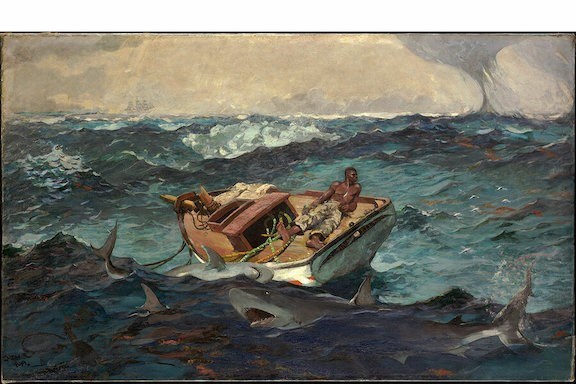

The Gulf Stream,” which Homer painted in 1899 and reworked in 1906, can be viewed as a scene of man against nature, or as a reference to the plight of formerly enslaved people.The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Gulf Stream,” which Homer painted in 1899 and reworked in 1906, can be viewed as a scene of man against nature, or as a reference to the plight of formerly enslaved people.The Metropolitan Museum of Art

June 7, 2022

People think they know the work of American artist Winslow Homer. His boisterous paintings of the Atlantic coast and of scenes such as barefoot boys playing a game of Snap the Whip are comfortingly familiar to many art lovers. But Homer (1836-1910) also made paintings that challenged viewers, both in his time and now in ours, to wrestle with the effects of racism and inequality.

“There’s a different Winslow Homer for every age,” says Sylvia Yount, who, along with Stephanie Herdrich, curated the exhibition “Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In an interview, the curators explained that they wanted to introduce Homer to the next generation, which involves tying the preoccupations of his day to those of our own.

The exhibition presents 88 oils and watercolors as proof of Homer’s sociopolitical concerns, hinting at a more profound dimension to his art. The common traits are tension, ambiguity, and, in his paintings of Black figures – which constitute a small but potent aspect of the exhibition – an insistence upon investing those images with the same realism that he displayed in painting white subjects.

Homer began his career in the 1860s as an illustrator and war correspondent for Harper’s Weekly, and the period he lived through was turbulent. The nation broke apart during the Civil War (1861-65) and tried (and in many ways failed) to find a path forward during Reconstruction (1865-77). Although the artist left scant record of his convictions about race, his paintings of Black people are unlike those of his contemporaries.

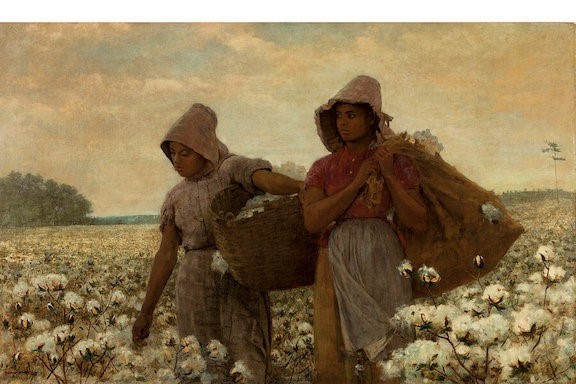

Digital Image ©2021 Museum Associates LACMA. Licensed by Art Resource, NYEarly in his career, Homer traveled to the American South, where he painted “The Cotton Pickers” in 1876. His images of Black people avoided racial stereotypes.

Digital Image ©2021 Museum Associates LACMA. Licensed by Art Resource, NYEarly in his career, Homer traveled to the American South, where he painted “The Cotton Pickers” in 1876. His images of Black people avoided racial stereotypes.

His images were “really bold, really different,” says Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, associate professor of art history at the University of Pennsylvania. In an interview, she explains that before Emancipation, artists had elicited sympathy for enslaved people by portraying them on the auction block, for example. But the market for such work evaporated after the mid-1860s, when, she says, “Very few fine art painters continued to paint Black subjects.” Caricatures derived from minstrel shows appeared in paintings, but “it was really unusual for Homer to stake so much on Black subjects connected to Reconstruction,” Professor Shaw says.

An early work, “Near Andersonville” (1866), is laden with symbolism. An enslaved Black woman stands at the threshold of a shack, emerging from darkness to confront an unknown future. In the background, Confederate soldiers march Union captives off to a notorious prison camp, Andersonville in Georgia, where nearly 13,000 prisoners of war died under horrific conditions. Ten years later, Homer painted “A Visit From the Old Mistress,” an uncomfortable scene in which three Black women receive their former white enslaver with stoic dignity.

“Dressing for the Carnival” (1877) demonstrates that Homer “is trying to immerse himself in a scene of Black life that seems authentic,” Professor Shaw says, “not a minstrel show onstage, not a saccharine, Currier and Ives scene of happy slaves dancing beside the river.” She adds, “They’re not performing for you. Rather, they’re living their daily lives.”

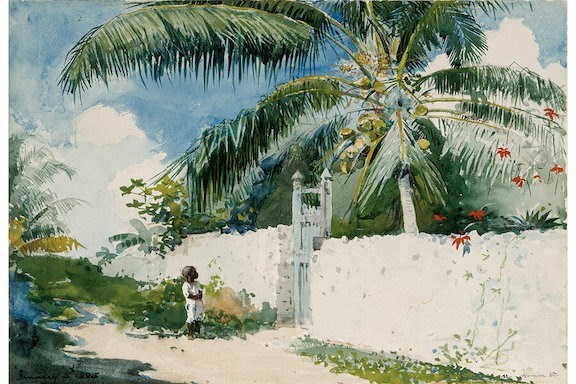

When Homer visited the Bahamas in 1885, his palette lightened and brightened. It’s difficult to view his dazzling watercolors, full of edenic tropical foliage and sunny reflections on turquoise water, as anything other than benign. But even here, he suggests an undertow of disharmony.

“A Garden in Nassau” (1885) implies social stratification and exclusion. A Black child stands outside a wall enclosing a private garden, looking at a coconut palm waving in the breeze. “Homer’s edits to ... the composition really give us insight into the meaning of [the] work and shift the tone,” Ms. Herdrich says. Originally Homer included two Black youths who climbed the wall to snatch coconuts. After Homer deleted them, she says, “there’s a completely different sentiment.” The mood is poignant, with a young child isolated outside a lush garden most likely belonging to a white landowner.

Homer’s watercolors from the Bahamas exult in scenes of strong Black men on boats in their quotidian labor of diving for sponges, coral, and conchs. Yet the sensuality of the scenes doesn’t negate his eyewitness rendering of slavery’s aftermath. “Homer is not looking at the luxury grounds of his hotel as a tourist,” Ms. Herdrich points out. “He’s exploring the Black settlements of Nassau [and] showing in an aestheticized way the harsh realities of a post-slave economy.”

Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago, Art Resource, NYHomer painted the 1885 “A Garden in Nassau” on a trip to the Bahamas. In it, he depicts a Black child excluded from the garden of a presumably white landowner.

Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago, Art Resource, NYHomer painted the 1885 “A Garden in Nassau” on a trip to the Bahamas. In it, he depicts a Black child excluded from the garden of a presumably white landowner.

The culmination of Homer’s two visits to the Bahamas was his masterpiece, “The Gulf Stream” (1899, reworked 1906). Professor Shaw sees the painting of an imperiled but resolute Black man, in a dismasted, rudderless boat surrounded by sharks, as the opposite of Homer’s optimistic early work, “Breezing Up: A Fair Wind” (1873-76). In the latter, white children steer a catboat heeling at a rakish angle. Yet they’re in control of their direction and destiny, “enjoying their mastery over nature,” Professor Shaw says.

The composition of “The Gulf Stream” bristles with symbols related to slavery. In the earlier version, depictions of sugar cane on the deck were minor. By giving them prominence in the latter version, Homer suggests the role of the Gulf Stream in the trafficking of enslaved people and the transportation of the product of their labor, sugar.

As an allegory of relentless nature and humans surrounded by insurmountable forces, the meaning of “The Gulf Stream” is unclear: Is Homer signaling fortitude in the face of adversity, or resignation? “His intention was for its meaning to be uncertain,” Ms. Herdrich says, “and to challenge us.”

“The genius of Homer is his ambiguity,” Ms. Yount says. “That’s what makes his art speak to us today.”

Ms. Herdrich agrees. “The relevance of the questions Homer asks is foundational and fundamental to our country, and [they] really resonate today,” she says. “We’ll be asking different questions in a different moment, and that’s the mark of a truly compelling artist.”

William Cross, author of a new biography, “Winslow Homer: American Passage,” says in an interview that Homer “told truths that are sometimes painful, but he was unflinching in his examination of who we are.”

Homer himself, in Cross’ examination, was a man of “many images but few words.” In a rare utterance on his work, Homer scoffed at a critic who praised Homer’s technical bravura, insisting to his dealer in 1902 that the picture in question “is not intended to be ‘beautiful.’ There are certain things (unfortunately for critics) that are stern facts but are worth recording as a matter of history.”

“Winslow Homer: Crosscurrents” continues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through July 31. A smaller version travels to London’s National Gallery as “Winslow Homer: Force of Nature” from Sept. 10, 2022, through Jan. 8, 2023.

Page created on 6/13/2022 4:50:12 PM

Last edited 6/13/2022 5:54:12 PM