REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION FROM THE CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR

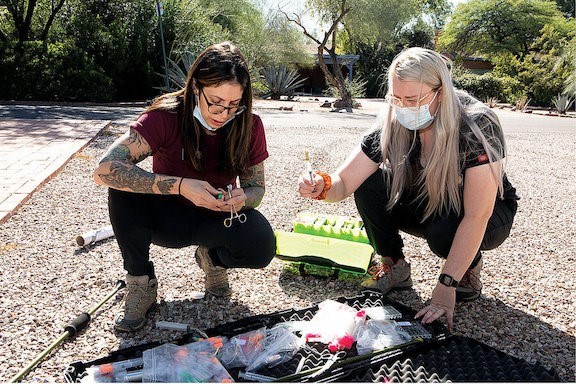

Dr. Sara Wyckoff (left) prepares a tranquilizer with help from vet tech Mariah Spicer as they rescue a javelina for the Tucson Wildlife Center in Arizona on Oct. 15, 2021.Melanie Stetson Freeman/CSM Staff

Dr. Sara Wyckoff (left) prepares a tranquilizer with help from vet tech Mariah Spicer as they rescue a javelina for the Tucson Wildlife Center in Arizona on Oct. 15, 2021.Melanie Stetson Freeman/CSM Staff

October 15, 2021

The call came in on a Friday morning. A javelina, a beloved boarlike animal that frequents this desert region, was lying in Vi Conaty’s front yard. It had been there since the night before, nestled between a boulder and a garden sculpture of St. Francis, and it still hadn’t moved.

“This is the middle of town,” said Lisa Bates, founder and executive director of the Tucson Wildlife Center, the organization Ms. Conaty had called for help, thanks to the advice of a 911 dispatcher. “Javelinas should not be in the middle of town.”

Ms. Bates squinted at the iPhone pictures Ms. Conaty had sent. “It’s hard to know if it’s napping. Or anything,” she said. “Maybe it’s been hit by a car.”

Wildlife veterinarian Sara Wyckoff and veterinary technician Mariah Spicer grabbed their truck keys. “We’re going to get her,” Dr. Wyckoff announced.

Ms. Bates nodded.

“Let me know,” she said.

Ms. Bates started the Tucson Wildlife Center more than 20 years ago to help wild animals like this: creatures in need, and especially those injured by encounters with the expanding human population of Tucson. At the time, she had recently retired from her career in plant science, and wanted to go into wildlife rehabilitation – a job that had become increasingly professionalized throughout the 1980s and ’90s. She had always loved the creatures of the desert, she explained. The first animal she rescued as a child was an orphaned raccoon. She would eventually raise coyotes and javelinas and bobcats – any animal, really, that she found struggling. “I love every species,” she says. “From the little javelinas and big javelinas to a skunk.”She opened her nonprofit organization in 2000, mostly taking in larger animals that other wildlife centers in the region couldn’t handle, like bobcats and coyotes. But one by one, she says, those other wildlife rehabilitation centers closed. The people who ran them retired, or they moved to other regions. By 2015, hers was the only wildlife facility left in southern Arizona, and she decided to build a wildlife hospital. She also agreed to take the 1,500 or so smaller animals – from baby birds to orphaned bats to injured jackrabbits – that had been under other rehabilitation centers’ care.

Melanie Stetson Freeman/CSM StaffStaff Lisa Bates started rescuing wild animals as a child. Today, she helms the Tucson Wildlife Center.

Melanie Stetson Freeman/CSM StaffStaff Lisa Bates started rescuing wild animals as a child. Today, she helms the Tucson Wildlife Center.

The Tucson Wildlife Center, she was determined, would help all creatures. “We have a respect for all life,” she says. “It doesn’t matter if it’s a little lizard or an elephant. If it needs help, we’re here for it.”

Today, that means the nonprofit takes in 5,000 animals a year. About 200 are on site at any given time, from the animal intensive care unit to the flight rehab enclosure. A handful of animals that cannot return to their natural habitats, whether because of injury or because of their acclimation to humans, stay at the center; the resident bobcats serve as “foster moms” for orphaned cubs.

Often, the first step for the Tucson Wildlife Center’s staff is to retrieve animals in distress. After all, as Ms. Bates says, “We don’t think it’s a good idea for a member of the public to put a full-sized javelina in their car.”

Which is why that Friday morning, Dr. Wyckoff and Ms. Spicer drove to central Tucson.

Emergency response

Unlike domestic pigs, javelinas, which can weigh 60 to 90 pounds, have sharp canine teeth and are prone to charging if they feel under attack. To fully examine the animal in Ms. Conaty’s front yard, then, Dr. Wyckoff knew she would likely have to anesthetize it and bring it back to the wildlife center. “We’ll assess the situation,” she said from the passenger seat as Ms. Spicer drove toward town.

The animal was still a few feet from Ms. Conaty’s porch when they arrived. It did not run when Dr. Wyckoff approached, but it clacked its teeth softly – a weak warning behavior. Dr. Wyckoff decided that she would use a blow dart to sedate the animal. The center’s veterinarians and techs encounter their patients in all sorts of ways. A raven flies into a window; a motorist hits a coyote; a jackrabbit is found in a trap. Sometimes people bring the animals themselves to the Tucson Wildlife Center, which sits on the eastern edge of town, nestled in ranchland by the Saguaro Mountains. Ms. Bates has met people who have taken injured animals on the bus because they didn’t own cars, walking the rest of the way to the center; she knows people who have driven for hours in the hopes of getting help for a suffering bunny, a downed starling.

The center runs a 24-hour emergency hotline. Two full-time wildlife veterinarians take lead on the recoveries, but Ms. Spicer often goes out on rescues.

“I had this one day when I went on a rescue to get a woodpecker across town,” Ms. Spicer recalls. “Then there’s a call – there’s a bunny. So I figure, I’ll stop and get the bunny. And then I get a call about a bat. ... And we’re driving and I got a call for a great horned owl. So now I’m holding this great horned owl, wrapped in a towel. It’s like a joke but it wasn’t. Oh! And there was a box of baby quails, too.”

That day, the javelina was the only call. Dr. Wyckoff walked slowly toward the animal, crouched down, and blew the dart into its side. It was 10:02 a.m. At 10:07 she checked the animal. Almost out, but not quite. A minute later, she hoisted it up and brought it to a carrying cage in the trunThe closer evaluation made her worried.

She suspected it had been hit by a car.

Melanie Stetson Freeman/ CSM StaffVeterinarian Sara Wyckoff, seen carrying a tranquilized javelina, rescues wild animals for the Tucson Wildlife Center.

Melanie Stetson Freeman/ CSM StaffVeterinarian Sara Wyckoff, seen carrying a tranquilized javelina, rescues wild animals for the Tucson Wildlife Center.

“It’s our nature”

In the world of wildlife conservation, there is regular debate about how much humans should interfere – whether nature should be left to simply “take its course.”

Ms. Bates has thought about this. She has. But the problem with this idea, she says, is that it assumes a “natural” ecosystem – a place where humans haven’t squeezed animals’ habitats, where we don’t drive cars across hunting ranges, where we don’t put toxins on the land and excessive carbon in the air, and where we don’t take the water – so much water – for our own needs.

If that were the reality, then maybe she could turn away from an injured owl or bunny. Maybe. But that’s not what we have, she says. We have a land and ecosystem dramatically changed by humans. So humans need to help.

“It’s our nature to save a baby,” she says.

But in wildlife veterinary medicine, “saving” can be complex. Dr. Wyckoff explains that her decisions would be different if her patient were a pet dog, who would be cared for through recovery, and fed even if he limps. If a wild animal is injured to the point where it might never be able to live in its habitat, or might face complications down the line, she often decides that the kindest act is to end the animal’s suffering.

And that was her decision as she examined the X-rays of the javelina.

Ms. Spicer bent over the animal. “I’m sorry, sweetie pie,” she said.

They left the examination table. There were dozens more animals to help. Dr. Wyckoff reviewed the list of patients. She checked on the great horned owl in the intensive care unit, running her hands through its feathers. His wing was recovering nicely.

The red-tailed hawk, whose X-ray had revealed a dozen buckshots, was also healing, although its wing would need more time. The jackrabbit in intensive care was doing well. Across the treatment room another staffer fed a nighthawk. A turtle was recovering beside them. This, Dr. Wyckoff says, is how she and the others at the Tucson Wildlife Center can live their commitment to the world around them.“I think you just have to do what nature says to do,” Ms. Bates said. “To save, wherever you can.”

Page created on 12/21/2021 4:01:23 PM

Last edited 12/21/2021 4:25:20 PM