REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION FROM THE CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR

On March 10, Lily Gladstone could win an Academy Award for her performance in “Killers of the Flower Moon.” She would be the first Native woman to receive an Oscar – after a century of work that has tended to go unrecognized.

Lily Gladstone and director Martin Scorsese are shown on the set of “Killers of the Flower Moon.” Ms. Gladstone has been nominated for an Academy Award for best actress. Melinda Sue Gorman/Apple TV+/AP

Lily Gladstone and director Martin Scorsese are shown on the set of “Killers of the Flower Moon.” Ms. Gladstone has been nominated for an Academy Award for best actress. Melinda Sue Gorman/Apple TV+/AP

Lily Gladstone’s high school yearbook named her “Most likely to win an Oscar.”

But in 2020, the actor’s career was faltering. Four years earlier, film critics associations in Boston and Los Angeles voted her best supporting actress for the drama “Certain Women.” Yet Ms. Gladstone faced a similar challenge as other Native American actors – a dearth of roles. She questioned whether acting was a sustainable path.

“I had my credit card out, registering for a data analytics course,” the actor told The Hollywood Reporter. At that moment, she received an invitation for a Zoom call with Martin Scorsese. He subsequently cast her in “Killers of the Flower Moon.”

On March 10, Ms. Gladstone’s performance could win an Academy Award for best actress. (If she does, there will be a stampede to see whom her yearbook picked as “Most likely to become president.”) A victory would be historically significant: She would be the first Native woman to receive an Oscar.

Indigenous actors don’t often appear at the podium at the Academy Awards. A recent study helps explain why. Stacy L. Smith, founder of the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative at the University of Southern California, discovered that less than a quarter of 1 percent of top-grossing movies released between 2007 and 2022 featured Native Americans in speaking roles. Just one movie starred a Native character in a lead role.

Native actors are often pigeonholed in Westerns, a genre that does not tend to reap statues during awards season. By contrast, television has started hosting more varied stories about Indigenous people. “The Lily Gladstone effect” – to use the term coined by Dr. Smith – may be to lift up other Native talent. And bring belated recognition to forebears in the industry.

“Native American actors and filmmakers have impacted movies for more than a century, but until recently their presence has passed largely unrecognized,” says Dr. Angela Aleiss, author of “Hollywood’s Native Americans: Stories of Identity and Resistance,” in an email.

Chris Pizzello/APLily Gladstone arrives at the Film Independent Spirit Awards, Feb. 25, 2024, in Santa Monica, California.

Chris Pizzello/APLily Gladstone arrives at the Film Independent Spirit Awards, Feb. 25, 2024, in Santa Monica, California.

Even many film buffs have never heard of Lillian St. Cyr. In 1914, Cecil B. DeMille cast her as the first Native American woman to play the lead role in a feature film. At a time when Westerns were more prolific than today’s Marvel movies, Minnie Provost also made her mark. The silent-movie comedian memorably sparred with Fatty Arbuckle in “Fatty and Minnie He-Haw.”

“Native characters have evolved in cycles over the past century,” says Dr. Aleiss. “The most negative cycle occurred during the late 1930s, where Natives were often portrayed as obstacles to frontier settlement (like in ‘The Plainsman’ and ‘Stagecoach’). Before and after that period, many sympathetic – although not always accurate – images existed.”

Nanticoke tribe member James Young Deer, who briefly ran Pathé studio in California, produced some of those films. In 1926, he directed “Tragedies of the Osage Hills.” It highlighted the systemic murder of Osage tribe members almost a century before Mr. Scorsese’s “Killers of the Flower Moon.”

Over subsequent decades, Native Americans seldom occupied positions of power in Hollywood. Those who did lifted others up. Jim Thorpe, the Olympic gold medalist and extraordinary baseball, basketball, and football star, lobbied for equal wages for Native American movie extras. Actor Will Sampson (“One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest”) co-founded the American Indian Registry for the Performing Arts in 1983. The nonprofit helped Kevin Costner’s best picture winner “Dances With Wolves” find its Native American cast, with Oneida member Graham Greene earning a nomination for best supporting actor.

Demand for Native actors still tends to fluctuate. Rick Mora often gets cast in what he calls “skin and bones” roles – half naked and wearing feathers. One such part was in “Twilight.” The 2008 teen vampire movie accounted for 29% of speaking roles in Dr. Smith’s aforementioned study. Even so, the blockbuster was criticized for casting Taylor Lautner in a major role as a Native character.

Hollywood is more mindful about casting Indigenous players today, says Mr. Mora, who’s grateful for the “Twilight” career boost. There’s an audience hunger for authenticity.

“Every culture is feeling the beauty of it,” says Mr. Mora, whose heritage is Yaqui and Mescalero Apache. “The African American culture is feeling the beauty of it. The Asiatic community is feeling the beauty of it. ... Now, our entire people are being sought after and viewed in a beautiful way.”

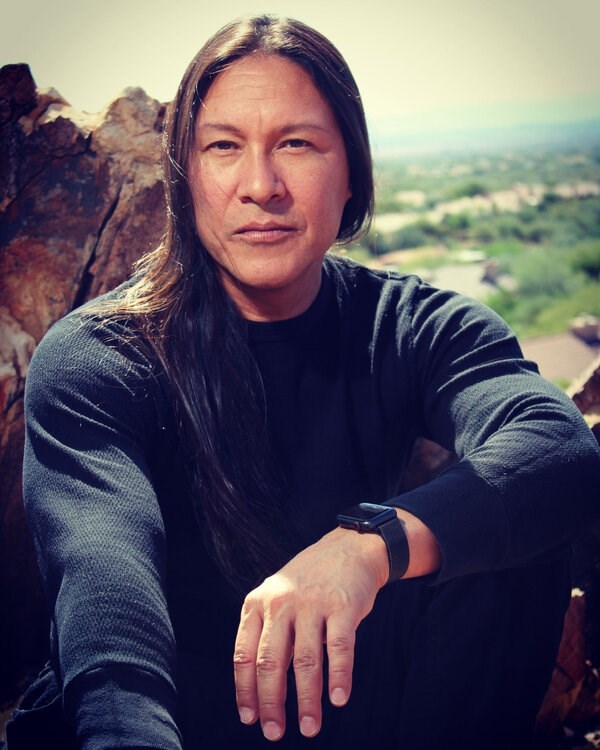

Cherrilyn SilvaActor Rick Mora, whose heritage is Yaqui and Apache and whose credits include “Twilight,” says Hollywood is more mindful about casting Indigenous players today.

Cherrilyn SilvaActor Rick Mora, whose heritage is Yaqui and Apache and whose credits include “Twilight,” says Hollywood is more mindful about casting Indigenous players today.

Television is leading the way. “Yellowstone,” like “Twilight,” features a mix of actors playing Native roles. Among them is Indigenous actor Q’orianka Kilcher, whose breakout role was Pocahontas in Terrence Malick’s “The New World.” Tribe members behind the camera are expanding the scope of Native American stories. Jhane Myers produced Hulu’s “Prey.” The prequel to the sci-fi horror movie “Predator” stars Amber Midthunder as a Comanche hero. Sierra Teller Ornelas co-created Peacock’s “Rutherford Falls,” a comedy about the fictitious Minishonka Nation seeking cultural recognition in a small town. And in Sterlin Harjo’s “Reservation Dogs,” a gang of teenagers commits petty crimes trying to scrounge enough money to leave their Oklahoma reservation.

“I don’t know how many times I’ve been in meetings throughout my career where people have said our Native stories don’t sell,” says Mr. Harjo in a phone call.

The humor in his hit series challenged outsider views of reservations as depressing and poor. It also illuminated the importance of women in those communities. To that end, Mr. Harjo cast Geraldine Keams in a matriarchal role. The Navajo actor launched her career in 1976 as an empowered, gun-toting character alongside Clint Eastwood in “The Outlaw Josey Wales.”

“I had known her work,” says Mr. Harjo, who adds that Native Americans in Hollywood are a small community. “We grew up on each other’s films and TV shows. ... Lily Gladstone probably wouldn’t be where she’s at right now without the people that came before us.”

Ms. Gladstone, who has a white mother and whose father is of Blackfeet and Nimíipuu heritage, spent her childhood on a reservation in Montana. She guest-starred in Seasons 2 and 3 of "Reservation Dogs" as Hokti, a character who is in prison. A non-Native writer might have envisioned Hokti as a male, says the showrunner. He wanted to reflect the reality that Oklahoma has a high number of incarcerated women, many of them Native. Mr. Harjo marveled at the depth Ms. Gladstone brought to the role.

“It’s not something that you can get from acting class,” says the writer. “That’s what I think is on display in ‘Killers of the Flower Moon,’ because she doesn’t talk a lot. She is this sort of moral center to the film. ... She’s representing all of us.”

Mr. Harjo and Ms. Gladstone recently reflected on the significance of her awards season. In February, she became the first Native actor to win a Screen Actors Guild Award. They agreed that those who open doors need to hold them open for others.

“This is going to be a celebrated time,” says Mr. Harjo, who will be watching the Academy Awards at home. “But it’s only the first step in this bigger thing that’s happening.”

Page created on 3/10/2024 10:42:55 PM

Last edited 3/10/2024 10:55:35 PM