John Wesley Powell was born in New York on March 24, 1834. He attended Wheaton and Oberlin Colleges, studied botany and geology, then joined the Union to fight in the Civil War. He lost his right arm at the Battle of Shiloh, but after a short time returned to the front until the war ended. This voluntary return to battle exemplifies Powell's determined character: He seemed compelled toward any task of immense difficulty. His explorations into the American West would prove to be the greatest efforts of his lifetime.

After the war, he became Illinois State University's first professor of geology, and also curator of its Museum of Natural History. While on a visit west in the spring of 1869, he decided to make a trip into the uncharted canyons of the Green and Colorado Rivers.

Powell was not the first to run the rivers and explore the canyons. Native Americans had been hunting, farming, and fishing in and around the river for thousands of years. The Spaniards, also, had crossed the land in the course of gold-seeking missionary tours. One group of Spanish travellers reportedly hacked steps down one side of Marble Canyon and up the other, in order to save the time of riding around it.

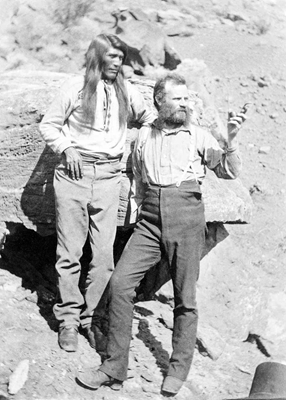

John Wesley Powell with Tau-gu, Chief of the Paiutes, overlooking the Virgin River (circa 1871-1874). Source: National Park Service. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

John Wesley Powell with Tau-gu, Chief of the Paiutes, overlooking the Virgin River (circa 1871-1874). Source: National Park Service. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

But Powell's was the first expedition with a scientific purpose--as Wallace Stegner says, "to fill the last great blank on the map of the United States." A brief list of what the explorers took with them reveals their values and purpose: barometers (for measuring elevation), sextants (for calculating latitude and longitude), chronometers (very precise clocks), thermometers and compasses. They packed enough food and clothing for 10 months; tools for boat repair; guns; ammunition; and traps for hunting. They brought a volume of Shakespeare's plays and entertained themselves by reading aloud the different parts. Powell brought his notebooks.

The river could be particularly rough: At least one party of white men had tried unsuccessfully to run the upper canyons of the Green in Northern Utah. After some of their men drowned, this first party abandoned the trip, leaving only scratch marks on a rock--"Ashley 1855"--an eerie reminder for future explorers. Powell himself had heard of an entire Native American family who drowned while journeying down the Green River. By stopping to study the rapids before running them, Powell and his men managed to get through safely. Although they had prepared for mishap by dividing up the cargo between their four different boats, they still lost plenty of instruments and provisions whenever a boat capsized.

Besides being a dedicated scientist and intelligent leader, Powell was also an extraordinary writer. His journal from the trip contains important scientific data, memorable incidents, and qualitative descriptions of the river and of the surrounding countryside. When it was published years later as "Canyons of the Colorado," the journal rewarded its readers with observations of unusual detail. Perhaps most interesting are his sketches of the men who accompanied him on his trip, such as this one of his brother:

"Captain Powell was an officer of artillery during the late war and was captured on the 22d day of July, 1864, at Atlanta and served a ten months' term in prison at Charleston, where he was placed with other officers under fire. He is silent, moody, and sarcastic, though sometimes he enlivens the camp at night with a song. He is never surprised at anything, his coolness never deserts him, and he would choke the belching throat of a volcano if he thought the spitfire meant anything but fun. We call him 'Old Shady.'"

Powell describes each of his colleagues with similar affection and humor. Like his brother, John Wesley keeps his cool: He never writes critically of the others nor complains about any of the mishaps they incur. In his notes, he neither self-aggrandizes or diminishes the others, but always bestows credit on someone else when possible. For example, he writes of a hike up to the rim of a certain canyon in which he found himself clinging onto the side of a cliff high above the river, unable either to go on or turn back. His companion, G.Y. Bradley, found his way to a ledge above, but could not reach down to Powell. Then, this man, whom Powell had characterized early in the trip as having "in danger, rapid judgment and unerring skill," took off the long johns he wore under his pants and lowered the end of one leg down. Powell let go of the rock (remember, he was hanging on by only one hand to begin with), grabbed the leg of Bradley's long johns, and let his friend pull him to safety. In this way, John Wesley Powell's life was saved by a pair of underwear.

Powell often scaled dangerous cliff sides to better examine canyon formations and the topography of the surrounding lands. A typical description goes like this:

"Below is the canyon through which the Colorado runs. We can trace its course for miles, and at points catch glimpses of the river. From the northwest comes the Green in a narrow winding gorge. From the northeast comes the Grand, through a canyon that seems bottomless from where we stand. Away to the west are lines of cliffs and ledges of rock--not such ledges as the reader may have seen where the quarryman splits his blocks, but ledges from which the gods might quarry mountains that, rolled out on the plain below, would stand a lofty range; and not such cliffs as the reader may have seen where the swallow builds its nest, but cliffs where the soaring eagle is lost to view ere he reaches the summit."

The trip did end sadly. Along the way, some of the boats capsized, dumping parts of their cargo each time, and now the party was low on food. On August 28, after much deliberation, three of the men decided to leave the expedition. Powell writes “some tears are shed; it is rather a solemn parting; each party thinks the other is taking the dangerous course.” Unfortunately, this danger was realized: The three men who climbed out of the canyon were killed as they made their way to a nearby settlement. Only a few days later, Powell and the others emerged from the Grand Canyon. They had nearly run out of provisions and were forced to end the journey after only four months.

Now equipped with a basic knowledge of the region, Powell followed up with even more careful explorations, studying, mapping and recording information about the land and its Native American inhabitants. He wound up at Washington DC, where he founded and directed the Smithsonian Institution's Bureau of Ethnology for the study of Native American languages and cultures. For a time, he served as head of the U.S. Geological Survey. He died in 1902 and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Powell's geographic and cartographic work made the canyons of the Green and the Colorado accessible to generations of Americans. Even today, people find adventure in running these rivers, although the routes are well-known and true dangers minimal. One can imagine that for Powell, leading that first trip into terra incognita, simply to begin required curiosity and courage of heroic proportions.

Page created on 6/25/2004 5:37:51 PM

Last edited 3/22/2020 6:28:57 AM