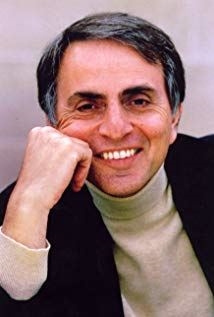

Renowned astronomer Carl Saganwww.imdb.com“The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It's not that there's something new in our way of thinking - it's that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before.¨ (Sagan) This thought from science educator Carl Sagan well explains the need for an analytical and critical public; it was well-said, for in the era of the Cold War and atomic power, a public that could rationally respond to news was more important than ever before ("Carl Sagan."). Sagan is not remembered only for this reflection on improving the public mindset, but also for all he has done to make good on it. The astronomer has worked extensively on NASA projects, like the Mariner probe to Venus and Voyager probe that eventually traveled outside the solar system. He has appeared on well-televised media like the Late Show with Johnny Carson spreading scientific news to a curious audience. He also wrote several texts such as The Dragons of Eden: Speculations on the Evolution of Human Intelligence, published 1977, and articles advocating against nuclear war, the most notable of which appeared in Parade magazine, published 1983 ("Carl Sagan."). Sagan died on December 20, 1996, but the astrobiologist is still renowned and remembered world-wide by the generations of scientists whose curiosity was sparked by his efforts. However, his fame and success are not what makes him a hero. Instead, Sagan´s caring use of his fame to promote world peace and help those close to him, and his determination to educate the public are why many remember him as a hero of science.

Renowned astronomer Carl Saganwww.imdb.com“The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It's not that there's something new in our way of thinking - it's that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before.¨ (Sagan) This thought from science educator Carl Sagan well explains the need for an analytical and critical public; it was well-said, for in the era of the Cold War and atomic power, a public that could rationally respond to news was more important than ever before ("Carl Sagan."). Sagan is not remembered only for this reflection on improving the public mindset, but also for all he has done to make good on it. The astronomer has worked extensively on NASA projects, like the Mariner probe to Venus and Voyager probe that eventually traveled outside the solar system. He has appeared on well-televised media like the Late Show with Johnny Carson spreading scientific news to a curious audience. He also wrote several texts such as The Dragons of Eden: Speculations on the Evolution of Human Intelligence, published 1977, and articles advocating against nuclear war, the most notable of which appeared in Parade magazine, published 1983 ("Carl Sagan."). Sagan died on December 20, 1996, but the astrobiologist is still renowned and remembered world-wide by the generations of scientists whose curiosity was sparked by his efforts. However, his fame and success are not what makes him a hero. Instead, Sagan´s caring use of his fame to promote world peace and help those close to him, and his determination to educate the public are why many remember him as a hero of science.

Sagan’s history of publicizing science stretched back to his youth. Through his determination it continued strongly, despite adversity from his colleagues. In his student years at college, Sagan was known for organizing public events about science. For this, he experienced widespread backlash:

Sagan next to a scale replica of a Viking series probe to Marswww.armaghplanet.comCarl's talent for publicizing science began to show itself in 1957 when he organized a successful campus lecture series...Carl invited lecturers and even gave one talk himself. Not all of the faculty were thrilled with what they saw as popularization and grandstanding. A disgruntled teacher called it "Sagan's Circus." Other faculty members criticized Carl for promoting scientific research to the public. One teacher took him aside and observed disapprovingly, “I've been following your career in the New York Times.” (Byman).

Sagan next to a scale replica of a Viking series probe to Marswww.armaghplanet.comCarl's talent for publicizing science began to show itself in 1957 when he organized a successful campus lecture series...Carl invited lecturers and even gave one talk himself. Not all of the faculty were thrilled with what they saw as popularization and grandstanding. A disgruntled teacher called it "Sagan's Circus." Other faculty members criticized Carl for promoting scientific research to the public. One teacher took him aside and observed disapprovingly, “I've been following your career in the New York Times.” (Byman).

Thus, as Sagan started publicizing science on a scale rarely seen before, he received much criticism from his superiors at the University of Chicago because of his resultant fame. Still, he persisted, which showed determination. Sagan risked his career by angering his professors. Eventually, these risks came to fruition. When Sagan reached the height of his graduate career at Harvard, he found it stymied by his critics:

Fred Whipple, the head of the Harvard astronomy department told him that he could not expect to be granted tenure, or the promise of a permanent job...Carl discovered that Professor Urey had written a letter criticizing him for the quality of his work...As soon as Carl learned he would have to leave Harvard, he started to look for another job...From the beginning, Carl's classes at Cornell were fully enrolled and his campus lecture series on science drew standing-room-only crowds. (Byman).

Sagan found his career halted at Harvard, but moved onto Cornell, where he was able to quickly resume teaching. As a result, Sagan’s setback at Harvard was not a major deterrent to his interest in teaching science to the public because of his diligence. The speed with which he continued teaching showed he was determined to pursue that interest. Thus, through his early and persisting involvement in publicizing science, against people who threatened to curtail his career, Sagan showed he had great determination.

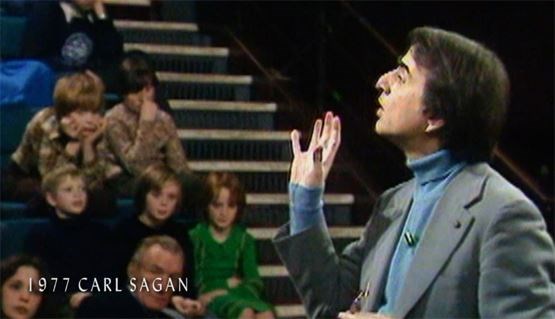

Sagan giving lectures to children at the Royal Institution in Londonblogs.loc.govAs he came into the public eye, Sagan gained reputation as a caring person both to the world at large and to those he knew personally. On occasion, he engaged in politics that mostly related to the Cold War and nuclear disarmament. In the climax of his involvement, he and several other scientists published an article on the aftermath of a nuclear war:

Sagan giving lectures to children at the Royal Institution in Londonblogs.loc.govAs he came into the public eye, Sagan gained reputation as a caring person both to the world at large and to those he knew personally. On occasion, he engaged in politics that mostly related to the Cold War and nuclear disarmament. In the climax of his involvement, he and several other scientists published an article on the aftermath of a nuclear war:

“Sagan sometimes used his prestige for political purposes, as in his campaign for nuclear disarmament and his opposition to the Strategic Defense Initiative of U.S. Pres. Ronald Reagan. In 1983 he cowrote the paper that introduced the concept of “nuclear winter,” a catastrophic global cooling that would result from a nuclear war” (Kragh).

Sagan used his fame to spread the news of how horrible an aftermath of a nuclear war would be. He could have used his fame to increase his personal wealth, like many famous people do today. Instead, he used it for something contradictory to two determined Soviet and American superpowers, either of which could have easily threatened him or his career. Sagan’s selfless use of his fame to help the world instead of himself showed that he cared about it. While he gained renown across the world for his political and public acts, those close to him experienced his caring firsthand. Sagan was known not only for his exciting lectures but also for his kindness towards his students. One of Sagan’s most notable students today, Neil DeGrasse Tyson, describes his first encounter with the professor:

“‘At the end of the day, he drove me back to the bus station. The snow was falling harder. He wrote his phone number, his home phone number, on a scrap of paper. And he said, ‘If the bus can’t get through, call me. Spend the night at my home, with my family.’” (Welsh).

Cover to the educational TV series "Cosmos", hosted by Saganwww.newvideo.comThus, Tyson describes the hospitality and concern Sagan showed for him. Most people would only extend invitations into their own home with people whom they have a solid familiarity, but Sagan did so after talking Tyson only once. In this way, his unusual kindness towards Tyson exemplifies Sagan’s great caring and that the people he knows are not the only ones entitled to it. Overall, through his public and personal deeds Sagan has demonstrated that he is a caring person.

Cover to the educational TV series "Cosmos", hosted by Saganwww.newvideo.comThus, Tyson describes the hospitality and concern Sagan showed for him. Most people would only extend invitations into their own home with people whom they have a solid familiarity, but Sagan did so after talking Tyson only once. In this way, his unusual kindness towards Tyson exemplifies Sagan’s great caring and that the people he knows are not the only ones entitled to it. Overall, through his public and personal deeds Sagan has demonstrated that he is a caring person.

"’Carl Sagan, more than any contemporary scientist I can think of, knew what it takes to stir passion within the public when it comes to the wonder and importance of science.’" (Alberts, "Carl Sagan."). Thus, Sagan was known for his skill at inspiring the young to take up an interest in science, because he was determined and caring enough to spark the next generation's interest in science. Sagan is remembered by DeGrasse Tyson: “‘I already knew I wanted to become a scientist, but that afternoon I learned from Carl the kind of person I wanted to become. He reached out to me and to countless others. Inspiring so many of us to study, teach, and do science.’” (Welsh). Thus, Sagan is an inspiring scientist and one deserving to be remembered as a hero, because of his desire to help the public and determination and caring while doing so. Many people may remember Sagan from a fleeting appearance on some TV show, but to the scores of scientists he has inspired he is remembered as the ideal scientist and a hero.

Works Cited

Byman, Jeremy. “Carl Sagan: In Contact with the Cosmos.” Carl Sagan: In Contact with the Cosmos, Jan. 2001, p. 8. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=b6h&AN=9762371&site=brc-live.00

"Carl Sagan." Scientists: Their Lives and Works, UXL, 2006. Student Resources In Context, https://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/K2641500182/SUIC?u=powa9245&sid=SUICx id=e433dbec. Accessed 7 Dec. 2018.

Kragh, Helge. “Carl Sagan.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 7 Dec. 2018, www.britannica.com/biography/Carl-Sagan.

Welsh, Jennifer. “The Inspiring Story of Neil DeGrasse Tyson's Life-Changing First Encounter with Carl Sagan.” Business Insider, Business Insider, 9 Nov. 2015, www.businessinsider.com/inspiring-story-young-neil-degrasse-tyson-met-carl-sagan-2015-11.

Page created on 1/9/2019 10:16:01 PM

Last edited 11/6/2019 7:45:59 PM