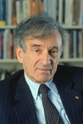

About Elie Wiesel

Elie Wiesel was born September 30, 1928 in Sighet, Kingdom of Romania, and died July 2, 2016 (aged 87) in Manhattan, New York.

Ten years after his liberation from Auschwitz, Elie Wiesel began writing about his experiences of the Holocaust. What emerged was Night, a memoir that offers one of the most powerful insights into life and death within the barbed wire confines of the concentration camps.

Wiesel grew up in a tight-knit Jewish community in Sighet, a small town in Transylvania. The Nazis came to Sighet in 1944 when Wiesel was 15, and all Jewish citizens were deported to concentration camps in Poland; he never saw his mother and younger sister again. Wiesel and his father managed to stay together in the camp until his father's death in the last months of the war.

After the war, Wiesel emigrated to France and, ultimately, to New York City. Since then, Wiesel has worked ceaselessly to promote understanding and equality, and to defend the causes of persecuted people throughout the world. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986 for his efforts to defend human rights. He and his wife, Marion, used the prize to found The Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity, to "advance the cause of human rights by creating forums for the discussion and resolution of urgent ethical issues."

Wiesel’s ongoing mission as a teacher, speaker, writer, and humanitarian is to make sure that the world never forgets the devastation of the Holocaust, and to remind all of humanity that we must never again remain silent when horrific crimes are committed.

To read more about Elie Wiesel click here

|

I am deeply skeptical about the very concept of the hero for many reasons and I am uncomfortable with what happens in societies where heroes are worshipped. As Goethe said, "blessed is the nation that doesn’t need them."

To call someone a hero is to give them tremendous power. Certainly that power may be used for good, but it may also be used to destroy individuals.

Which societies have proven to be the most fertile fields for the creation of heroes, and have devised the most compelling reasons for hero worship? Dictatorships. Stalin and Hitler were worshipped as gods by millions. It was idolatry, or worse, blind faith. Anyone who questioned the gods, knew too much, or rebelled in any way was finished.

Even if we do not worship our heroes, they may cow us. It takes a certain amount of confidence and courage to say, "I can do something. I can change this and make a difference." But if you, as a writer think, "What are my words next to those of my hero, Shakespeare?" then something is lost for those who need your help and your voice. Excessive humility is no virtue if it prevents us from acting.

So we need to be very careful of those we put on a pedestal, and choose only those who embody those qualities that reflect the very best of human nature. But even that is a dangerous game. What do we do with a hero who has done something less than heroic? None of our forefathers was perfect. Moses is probably the single most important figure in the Bible besides Abraham. He was a teacher, the leader of the first liberation army, a legislator. Without him, there is no Jewish religion at all. Yet of the many things he is called in the Bible, he is never called a hero, perhaps because he did not always behave heroically. He began his public career by killing an Egyptian; later, he failed to identify himself as a Jew. For these reasons and others, he is prevented from entering the Promised Land with the people he has led there. Is Moses a hero?

Is a hero a hero twenty-four hours a day, no matter what? Is he a hero when he orders his breakfast from a waiter? Is he a hero when he eats it? What about a person who is not a hero, but who has a heroic moment? In the Bible, God says "there are just men for life and there are also just men for an hour." Is a just man for an hour a hero? The definition itself and the question of who deserves the title are slippery at best.

I do believe in the heroic act, even in the heroic moment. There are different heroisms for different moments in time. Sometimes just to make a child smile is an act of heroism.

In my tradition, a hero is someone who understands his or her own condition and limitations and, despite them, says, "I am not alone in the world. There is somebody else out there, and I want that person to benefit from my sacrifice and self-control." This is why one of the most heroic things you can do is to surmount anger, and why my definition of heroism is certainly not the Greek one, which has more to do with excelling in battle and besting one’s enemies.

My heroes are those who stand up to false heroes. If I had to offer a personal definition of the word, it would be someone who dares to speak the truth to power. I think of the solitary man in Tiananmen Square, who stood in front of a column of tanks as they rolled in to quash a peaceful protest, and stopped them with his bare hands. In that moment, he was standing up against the entire Chinese Communist Party. I think of the principal cellist of the Sarajevo Opera Orchestra, who sat in the crater formed by a mortar shell blast and played for twenty-two days--one day to commemorate each one of his neighbors killed in a bread line on the same spot--while all around him, bullets whistled and bombs dropped. Those people were heroes.

Maybe heroes can simply be those people who inspire us to become better than we are. In that case, I find my heroes among my friends, family, and teachers. My mother and father's respect and love for learning had a great influence on me, and my son’s generosity and humility continue to inspire me.

It was my grandfather who allowed me--who obliged me--to love life, to assume it as a Jew, and indeed to celebrate it for the Jewish people. He led a perfectly balanced life. He knew how to work the land, impose respect on tavern drunks, and break recalcitrant horses, but he was also devoted to his quest for the sacred. He told wonderful stories of miracle makers, of unhappy princes, and righteous men in disguise.

When I was a child, my heroes were always anonymous wanderers. They experienced the wonder of the wider world and brought it to me in my small village. These men were masters. A master must give himself over to total anonymity, dependent on the goodness of strangers, never sleeping or eating in the same place twice. Someone who wanders this way is a citizen of the world. The universe is his neighborhood. It is a concept that resonates with me to this day.

In fact, it is to one of those wanderers that I owe my constant drive to question, my pursuit of the mystery that lies within knowledge and the darkness hidden within light. I would not be the man, the Jew, I am today, if a disconcerting vagabond--an anti-hero--had not accosted me on the street in Paris one day to tell me I knew nothing. This was my teacher Shushani Rosenbaum. He spoke thirty languages, and there wasn’t a country he hadn’t visited. He looked like a beggar.

I was his best student, so he tried to destroy my faith by demonstrating the fragility of it. This was his chosen role: the troublemaker, the agitator. I gave him my reason and my will, and he shook my inner peace, destroyed everything I felt to be certain. Then he built me back up with words that banished distance and obstacles. Learning this way was a profoundly disturbing experience, but a life-changing one. I have never stopped questioning and challenging what I believe to be true. I speak of him as a disciple speaks of his master, with tremendous gratitude, and his is the advice I give to young people, as well: "Always question."

In Hebrew, there is no word for hero, but there is one that comes close, based on the word for justice: tzaddik. A tzaddik is a "righteous man," someone who overcomes his instincts. In the ancient texts, this would mean sexual instinct, the life force, but of course it can be extended to all the emotions connected to that force: jealousy, envy, ambition, the desire to hurt someone else--anything, essentially, that you want to do very much.

There is a story about a tzaddik that says a great deal to me about the character of the true hero. This man came to Sodom to preach against lies, thievery, violence, and indifference. No one listened, but he would not stop preaching. Finally someone asked him, "Why do you continue when you see that it is of no use?" He said, "I must keep speaking out. In the beginning, I thought I had to shout to change them. Now I know I must shout so that they cannot change me."

Page created on 8/11/2014 7:13:22 PM

Last edited 8/2/2021 6:15:30 PM

© 2005 by The My Hero Project

MY HERO thanks Elie Wiesel for contributing this essay to My Hero: Extraordinary People on the Heroes Who Inspire Them.

Thanks to Free Press for reprint rights of the above material.