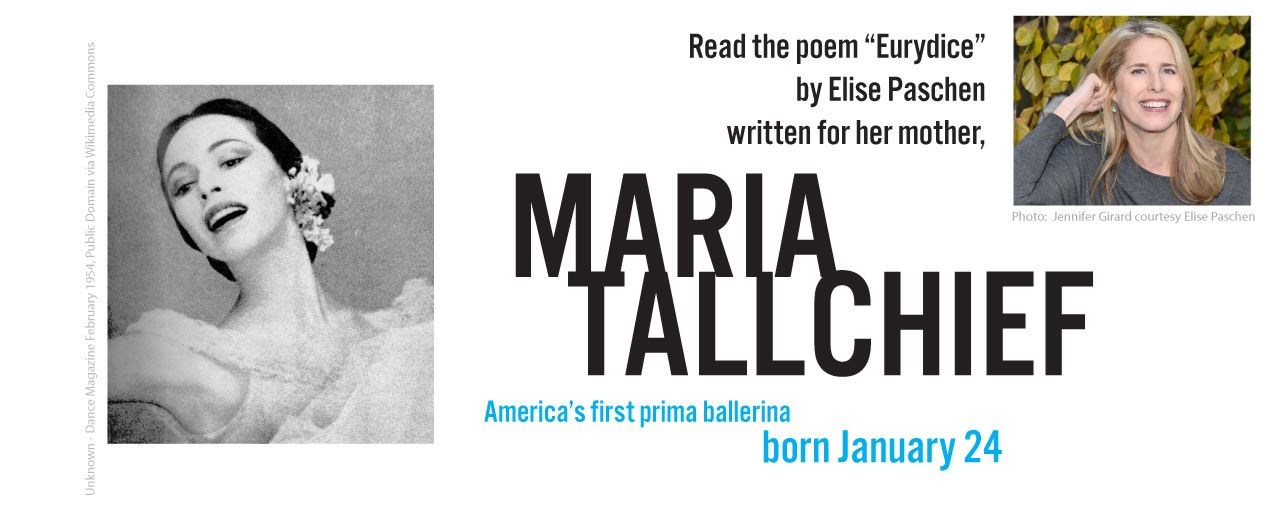

Maria Tallchief - Eurydice by Elise PaschenUnknown - Dance Magazine February 1954, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons | Photo: Jennifer Girard courtesy Elise Paschen

Maria Tallchief - Eurydice by Elise PaschenUnknown - Dance Magazine February 1954, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons | Photo: Jennifer Girard courtesy Elise Paschen

In 1947, when Kirstein and I agreed that Ballet Society should commission a new ballet from

Stravinsky, the composer consented to the project. He asked for

suggestions, and I told him that I would like to do a new, modern

“Orpheus.” It seemed to me that the Orpheus myth, with its

powerful portrayal of the poet-musician’s destiny and of his love,

was particularly appropriate for ballet, and particularly a ballet

with music by Stravinsky.

-- George Balanchine

You were all of twenty-three, married

to Balanchine. The nights he spent,

absorbed, at work on “Orpheus”

you felt alone, and stayed at home,

stitching an Indian patterned skirt.

But when you danced Eurydice’s

last pas de deux, you wrapped your arms

and legs around your poet husband,

“Orpheus,” willing him to look

into your eyes. As Balanchine

wrote: “tormented because she cannot

be seen by the man she loves.”

Attempting to seduce, you dance

the dance till finally he tears

away his mask, and you collapse

to earth and die. During rehearsal

Stravinsky asked, “How long to die?”

In the score he scratched five long counts.

The time of the ballet, “the time

of sand and snakes,” “of Greek earth legends”

wrote Balanchine. And Kirstein saw

(describing their Gluck’s “Orpheus”)

“the eternal domestic tragedy

between an artist and his wife.”

Your husband, armed with song, lays siege,

enchants the gods to claim you back,

vowing he will not look. But you

persuade him. Therefore Orpheus

throws off his mask, and loses you.

His mask becomes a lyre.

Mother, when I was young, I watched

you from the wings and saw the sweat

dripping from arms and neck, your gasp

for breath. I thought it was your last.

But no. You’d towel off, and then

step back into the spotlight, smiling.

Published in Bestiary (Red Hen Press, 2009). Reprinted here with permission.

Page created on 1/13/2020 1:45:46 AM

Last edited 1/19/2021 5:24:23 AM