The durability of the human spirit. It's truly a cause for marvel.

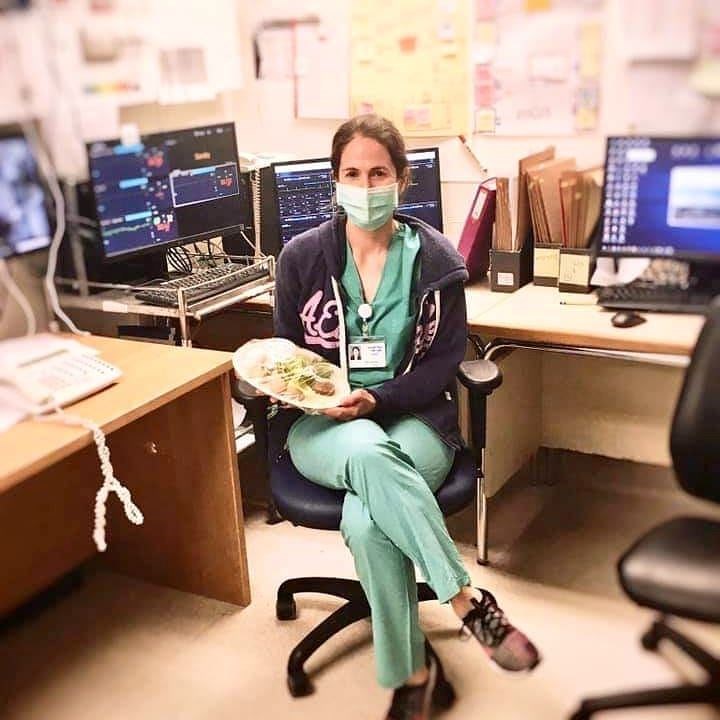

Rachel GemaraPhoto courtesy of Rachel GemaraWhen Rachel Gemara, 33, an oncology nurse, received a text message in late February from the hospital administration at Shaare Zedek Medical Center in Jerusalem, Israel, calling for volunteers for the not-yet-formulated popup unit to treat coronavirus patients, her immediate reaction was yes.

Rachel GemaraPhoto courtesy of Rachel GemaraWhen Rachel Gemara, 33, an oncology nurse, received a text message in late February from the hospital administration at Shaare Zedek Medical Center in Jerusalem, Israel, calling for volunteers for the not-yet-formulated popup unit to treat coronavirus patients, her immediate reaction was yes.

"I knew that we were gearing up for a war on the coronavirus, and as health care workers, we'd be on the front lines," explained Gemara. "I volunteered out of a sense of a national calling."

It felt like a moral imperative, a resolute commitment to care for people in the face of a pandemic.

But when she walked into the "Keter" isolation ward two weeks later for her first shift, she found that the job differed considerably from her habitual work as a nurse. ("Keter" is the Hebrew word for crown [corona in Latin], because the virus has little crowns on the exterior.)

In contrast to the standard units, the medical staff in the Keter (coronavirus) ward tried whenever possible to monitor patients from the safe distance of the “chamal” (Hebrew acronym for headquarters that literally means “war room”), a small room crowded with CCTV (closed circuit television), installed with monitors and a video intercom system. The patients had sensors affixed to their chests that continuously monitored their blood pressure, temperature, oxygen and pulse, and the results were projected on the screens.

"Caring for patients this way is nerve-wracking," acknowledged Gemara. "I appreciate that we have this technology that allows for this kind of communication, but it's challenging to make an assessment based on what I see on a screen. It's difficult to gauge how the patients are really doing." Nevertheless, she adjusted quickly.

However, as patients grew sicker, Gemara and her colleagues had to go into the ward, clad in protective gear from head to toe. That was no small feat.

Suiting up took ten minutes. Gemara stepped into a white hazmat suit and zipped it up. (Hazmat comes from the term "hazardous materials.") She pulled her long hair into a ponytail; put on an N95 mask, two sets of blue sanitized gloves, face shield and hood; and slipped booties over pink Nikes. Cuffs secured. An extra layer of safety was provided: An infectious disease nurse regularly watched all staff members don their gear as well as take it off to ensure that they didn't accidentally infect themselves.

Protected head to toe, Gemara buzzed into Keter.

During her first days in the isolation ward, she feared catching the virus. But then her concerns quickly dissipated. "I knew that the protective gear worked, and I learned how and when to move away if I had to do a procedure that could put me at risk."

While inside the Keter unit, Gemara appreciated being able to be physically close to her patients and function as a "proper nurse."

"Because of the situation, coronavirus patients don't get to see a lot of staff," acknowledged Gemara. "While on the inside, I could have real interactions. I savored that. I feel for them. They're in a very scary situation."

Gemara brings her own kind of sanctity and devotion to her nursing practice. Ten years clocked in an oncology ward where most patients are Stage Four and approximately thirty percent are terminal, she had invested in building relationships to make the end of life meaningful and to care for them when they passed on. To the task of working in the isolation ward, Gemara brought experience and a trove of emotional strength.

One evening stands out as stark and searing. On March 20, 2020, Gemara's seventh day in the unit and her fifth shift, she watched from the headquarters as Arie Even, an 88-year-old Hungarian Holocaust survivor, took his last breaths and passed away. He was Israel's first COVID-19 fatality. It felt like divine intervention that she, the granddaughter of a Hungarian Holocaust survivors, was the one to care for his body and say goodbye.

And then there's another night that sparkles with light.

Rachel Gemara holding a Seder plate in the wardPhoto courtesy of Rachel Gemara

Rachel Gemara holding a Seder plate in the wardPhoto courtesy of Rachel Gemara

On April 23, 2020, a smiling, bespectacled man tapped his glove-covered knuckles on the headquarters. Gemara’s face beamed exultant joy. It was her 51-year-old patient with no prior medical conditions who'd been admitted three weeks prior with severe respiratory distress, too weak to get out of bed.

The one who had stopped breathing.

Her voice welled up as she related the story.

“At 2 a.m. I was inside the unit, in full protective gear, the rest of the staff far away in the headquarters,” Gemara shared. “He had asked me to help him out of bed, and as I slowly helped him sit down, he suddenly slumped his head, his eyes rolled back and he completely lost consciousness. I was alone and terrified. His life was in my hands, and every second counted. I leaped to grab a 100% oxygen face mask from the crash cart and connected him immediately to the maximum amount of oxygen. Thank heavens he regained consciousness. The sheer terror and uncertainty of those few moments shook me to my core. It was clear he needed more intensive monitoring and care. Soon after, a doctor and I carefully wheeled him to the ICU Keter Unit, keeping a close eye during the transfer. Once there, I squeezed his hand and said: 'They’re going to take good care of you here, stay strong, keep fighting, I’ll pray for you and I'll see you again soon.' I walked back to my unit in tears, truly afraid that he might not make it."

And then there he was, fully recovered, beaming at Rachel. "You saved my life, plain and simple."

Those two stories encapsulate a nursing journey. Many are the lessons imparted for Gemara over the 320 hours she clocked in 12-hour shifts in Keter. The prevalence of compassion. The depth of her strength. The interconnected nature of people, and the tender threads that bind us, watching patients caring for each other in the isolation ward, now a family.

"The durability of the human spirit. It's truly a cause for marvel."

Page created on 5/12/2020 5:00:40 AM

Last edited 4/27/2021 9:52:40 PM

Ruth Ebenstein is an American-Israeli writer, historian, public speaker and peace activist who loves to laugh. She is writing a memoir, Bosom Buddies: How Breast Cancer Fostered an Unexpected Friendship Across the Israeli-Palestinian Divide. Ruth has published her shorter writing on both sides of the Atlantic and won two first-place Simon Rockower awards, sponsored by the American Jewish Press Association. Her writing has appeared in the Atlantic, Washington Post, Los Angeles Review of Books, School Library Journal, CNN.com, WomansDay.com, Tablet, the Forward, Stars and Stripes, Education Week, Brain, Child, Lilith and other publications. She has also penned a children’s book, All of this Country is Called Jerusalem. Find her online at ruthebenstein.com, on Facebook at Laugh Through Breast Cancer – Ruth Ebenstein, and on twitter @ruthebenstein.