|

As an architecture student at Yale University, William McDonough designed the first solar-heated house in Ireland.

"That gives you a sense of my ambition," he quips. "They don't have much sun in Ireland, but there's a lot of light."

McDonough was an art student when he discovered his calling. "I liked architecture because it involved lots of people and expresses something important about human intention."

McDonough has been designing buildings since the 1970s and has received numerous accolades for his work. In 1996, Bill Clinton chose him to be one of the first recipients of the Presidential Award for Sustainable Development. (The President's Council on Sustainable Development was quietly abolished by George W. Bush.) In 1999, Time magazine called him "A hero for our planet." McDonough's design for Herman Miller's furniture factory increased that company's productivity 1 percent ($3 million) in the first year, garnering Business Week's prize for the best and most productive building in America for business. Moreover, his design for the Gap Coroporate Campus is, according to Pacific Gas & Electric, the second most energy-efficient building in their territory. Most recently, the Duveneck Foundation bestowed upon him the "Hidden Villa Humanitarian Award."

He is also the co-founder of McDonough Braungart Design Chemistry, which works with the clothing, furniture, and automobile industries to create ecologically sustainable materials. Sarah van Gelder of Yes! magazine reported that the company's "research into fabrics and dyes free of toxins, mutagens, carcinogens, and endocrine disrupting chemicals led to a line of fabric so pure that the effluent water leaving the factory is cleaner than the water going in."

|

|

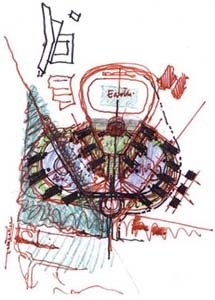

| A colorfully-sketched architectural idea becomes Nike's Corporate Office in the Netherlands. | |

McDonough spent much of his childhood in Hong Kong, where his father worked. There, he recalls people were only able to get water four hours every fourth day during the dry season. He witnessed a cholera epidemic when the McDonoughs "had people dying on our doorstep." He also saw extreme poverty and the humiliation of the poor.

"When my mother went to the money changer to change my father's checks, there would be an old woman there, begging, using a baby, crying, to elicit sympathy. She would have a new baby every two or three weeks. I thought that was normal life."

By contrast, McDonough spent summers in Washington's Puget Sound, at his grandparents' log cabin. His grandparents raised oysters, and they saved rubberbands and aluminum foil.

"I thought that was ordinary life," he explains. "When I became a teenager, we moved to Westport, Connecticut, where sixteen-year-olds had Porsches. And I realized that we had become consumers with lifestyles instead of people with lives. I learned that third-graders were being taught to dive under their desks in school drills, and I realized that we were living as if there was no tomorrow. Indeed we were creating the condition whereby there might be no tomorrow. It seemed to me that our culture was essentially partying it up, waiting for Armageddon, and that in a sense we were not only living as if there were no tomorrow, we were designing as if there were no tomorrow." From his grandparents, he got a "sense that the world is full of gifts."

In the 1990s, McDonough was comissioned to design Gap's new headquarters in Northern California. He wanted to design a building of "biological and technical nutrition" that would either "go back to soil safely or go back to industry forever." This is the notion that McDonough and his partner, Mark Brangart, call "Cradle to Cradle" design, the idea being that nothing used in building will be wasted. Everything will biodegrade or, when the building becomes obsolete, will be able to be recycled into materials for new structures. The building was made of glass, stone, and concrete. McDonough designs all his buildings for "adaptive reuse." This means that when Gap no longer wants to use the building as a corporate headquarters, the structure is such that it can easily be converted into living space, or used for some other appropriate use.

Most notably, the Gap building boasts a roof of native grasses that provide habitat for birds and insects. McDonough says he can tell how successful a building is by how many songbirds return to the site.

|

| Gap Corporate Headquarters in California. The roof provides habitat for songbirds and insects. |

In 1991, the city of Hanover, Germany asked McDonough to write out the general principles of sustainability for the 2000 World's Fair. These "Hanover Principles" have since become a mainstay of the sustainable design movement.

|

Page created on 8/9/2014 7:06:07 PM

Last edited 1/5/2017 9:57:06 PM