|

THE TERM “FORCE OF NATURE” is not typically employed to describe an octogenarian, but it seems to be a good fit for philanthropist and activist Eva Haller, who has recently turned 84. One of her mentees, Jessica Mayberry, says “she seems never to be tired.”

I see this for myself when I call to set up the interview with the 2014 recipient of the Magnusson Fellowship, whose members include Nobel Laureate Dr. Muhammad Yunus and former president of Ireland, Mary Robinson. Less than half her age, I feel exhausted just listening to her schedule for the day. Board meeting, board meeting, lunch, doctor’s appointment, meeting. She has a small window from 6:00 to 6:30PM before a dinner party, she offers. We decide it’s better to meet on a less packed Sunday afternoon.

Things are lively at her uptown Manhattan residence when my cameraman and I arrive. We are greeted by her husband, Dr. Yoel Haller, former Medical Director of Planned Parenthood in the Bay area. I’m surprised to find their home filled with guests and the din of conversation. “It’s always like this,” he says, motioning us in. We wait while taking in the view of the city skyline and the modern art in their home.

Eva arrives. Her face is soft and bird-like, but her eyes are piercing. I have been forewarned that she can be almost cruel in her honesty. When she looks at me, I’m reminded of being in the dentist’s chair: there is the distant sensation of something drilling down deep, and, while painless, you sense how close to the nerve it is.

|

Those eyes belonged to a 14-year old girl who famously convinced a Nazi soldier to spare her life because she was “too young and too beautiful to die.”

Most accounts of Eva’s life begin with this breathtaking story, then continue with the numerous causes taken up by a woman who sought to transform whatever life brought near her. “Eva has sat on more boards than I’ve had hot dinners!” laughs friend Kathy Eldon while describing her. My head swims as I try to keep track of the mission statements of the boards of the non-profits on which she’s formally served. I’m aware of 22.

The director of The MY HERO Project, Jeanne Meyers, tells me there’s a recent BBC interview with Eva which I should listen to for my research. It turns out to be unavailable for download in the US. By what seems like some psychic insight, Eva brings up exactly this omission as she sits down by my side. In a musical Hungarian accent, she asks me whom I have interviewed. She notes that the names belong to younger women who have mostly had a straight path, but her life has not been so straight, and so it is very difficult for someone to interview her.

Funny, I think glumly, I had reached a similar conclusion on my own. She goes on to tell me she was recently interviewed by a journalist from the BBC who had really done her homework, to a scholarly level. And so she truly enjoyed that interview, and thinking about the questions, and answering them, because she was given questions she had never been asked before. I wonder how a person can be so gentle and pointed at the same time. I wryly consider my options in light of this high standard: Panic? Despair?

I manage to say that I have a set of questions, but I’d like to see which way the conversation goes. “Alright,” she says, rising to leave the room for a moment, “I am here to serve you.”

One of her guests, Sunny Jacobs, whose experiences being unjustly convicted for a capital crime were depicted in the play, The Exonerated, looks at me and says, “She is so wonderful. And she is a great mentor. Even now, she was mentoring you.”

EVA’S OLDER BROTHER JOHN worked in the underground as part of the Hungarian resistance in 1942. He “allowed her in on some of the adventures,” printing and circulating anti-Hitler pamphlets in Budapest.

While crossing into Yugoslavia to join Tito’s forces, he saved the lives of his three friends by giving himself up to the enemy. Eva is said to have taken this loss and dedicated her life to helping others in his memory. “Losing him was the greatest sorrow of my life,” she says.

It is estimated that over half a million Jews were deported and killed under Adolf Eichmann during the German occupation of Hungary, which began in March of 1944. During this period, her parents hid her in the Scottish Mission of Budapest. Its matron, Jane Haining, was a British citizen, but had refused to abandon the children in her care and was arrested by the Gestapo. One of the charges leveled at her was weeping when she saw the yellow stars on the clothes of the Jewish girls in her care.

“Not until recently did I find out that the woman who was the head of the Scottish mission was taken to Auschwitz and died in a gas chamber,” says Eva. “She was not Jewish…And she saved my life by allowing me to be there, for at least those couple of months when the Nazis were doing their most vicious killing. And thus I owe a great debt to the Scottish nation.”

I ask about her courage in persuading a Nazi soldier to let her escape during a raid on the mission, and saving a neighbor’s son. She chooses her words carefully, musing, “I think that courage is different than the desire and force of survival. You know, I really am afraid of the dark when I’m alone. I’m not a very courageous person. This question about facing the Nazis and saving that kid’s life was sort of like, ‘Hey! c’mon man! You are a young officer…you really want this on your head? my blood?’” she says, her face breaking into a grin. “[Although] I didn’t say that. I just told him that I’m much too young and too beautiful to die.”

She quips about those memorable words which saved her life: “And he was rather surprised because yes, I was young, but I wasn’t beautiful!”

EVA BRINGS UP SURVIVAL AGAIN when recounting her immigration to the US, initially to study psychology: “When you arrive at a country and you have a 6-weeks visa, and then you stay on illegally, and you clean houses because that was the only way to make a living and go to school at night, you really don’t think too much about anything other than ‘How many credits do I need? How will I survive? is this lawyer going to help me get my student visa?’ All kinds of survival issues come to your head. And you try to find shortcuts to make it all happen.”

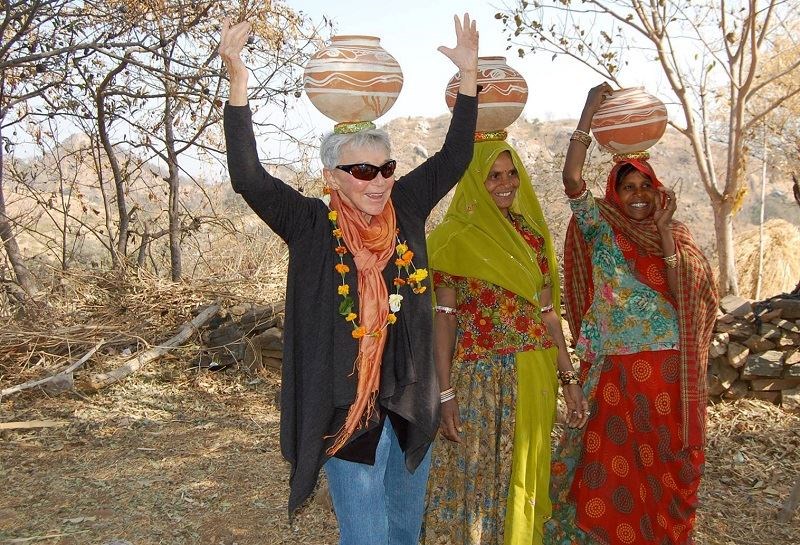

|

It was while working in the lower east side of New York that she discovered what she really wanted to do: “I remember asking my supervisor one day, is it alright if I scream when I see a rat?” she says. “It was so scary–the way that people had to live under terrible conditions. I was trying to help them so that they can get a coat from the Welfare department, so that they get food stamps, so that I can help the kids to get into school. And I realized that that…I really don’t want to be a clinical psychologist. I don’t want to test people. I just really–I want to move into people’s lives. I want to manipulate environments.”

She went back to school and got her M.S.W. (Master of Social Work degree) from Hunter College. “That was a good move,” she says, looking back with a pleased expression. “And once a social worker, you know? You’re always a social worker.”

IN 1967, EVA FOUNDED the Campaign Communications Institute of America, a political telemarketing company, with her husband, the late Murray Roman. She had liked the one-to-one, direct impact of social work, and the idea of working in a world where “the customer is always right” gave her a “big migraine headache.”

“I really saw myself as a helper rather than a business woman. But we met late in life. I was 35, and he was 45, and I was deeply in love. And the idea that maybe we can do something together and be together 24 hours a day was something that truly appealed to me,” she says.

“We started our business and we made an awful lot of money. The awful lot of money was exactly a million dollars. So we decided that that was terrific; we closed shop and offered UNICEF our services.” The couple traveled to Cambodia, the Philippines, Thailand, Australia, and Hong Kong, teaching in the field of communication.

“The whole trip was a dream,” she recalls. “Everything made a big impact on me. Going to Cambodia and being in Angkor Wat, meeting Prince Sihanouk, and meeting all the rulers in Thailand. Being in the palace with Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. That whole period of getting to know the opposition leaders and trying to work with them against the Marcoses was a very heady and powerful time for two New Yorkers.”

They came back to New York (“because apparently a million dollars is sort of like, not exactly something that lasts as long as we thought it would!” she jokes), and began establishing businesses in Australia and Europe, as well as reopening Eva’s office in the US. It was at this time that they began to pursue philanthropy.

“We were a magical and very successful couple and had some very amazing moments in life,” she says, “Mostly in the civil rights movement, in the feminist movement.”

|

ONE OF THOSE MOMENTS WAS IN 1965. In his speech at the end of the historic march from Selma to Montgomery, Dr. Martin Luther King stated, “Selma, Alabama, became a shining moment in the conscience of man. If the worst in American life lurked in its dark streets, the best of American instincts arose passionately from across the nation to overcome it.” The country had recently witnessed on television the brutality of the police on Bloody Sunday, with their use of dogs and clubs. There had been the murders of Jimmie Lee Jackson and James Reeb.

Eva was one of the 25,000 who acted on the “best of American instincts.” She went to Selma to take part in the march that led to the signing of the Voting Rights Act, the landmark legislation which most effectively enforced the prohibition of discrimination in voting.

Eva has a personal connection to Dr. King: “You know, Martin Luther King III is a friend of mine. He was 9 years old when his father did the Montgomery march. And I asked him a few months ago when I was talking with him, ‘Where were you?’ And he said ‘My parents didn’t take me to the march, they were fearful for me, so I didn’t go.’ But I took my 15-year old son, and I didn’t realize how scared I should be, until we got there, and the Sheriffs with their big sticks and the German Shepherds on the leash. It was scary.” Shortly after the march, the Klu Klux Klan assassinated Viola Liozza, a housewife and activist from Detroit who had been taking marchers back from Selma to Montgomery.

Taking part in history has real risks, as well as consequences. But it can also lead to moments of a deep connection with our humanity, which come once in a lifetime: “When the march was over, and we had to get on a plane…we needed to get into a car to get us to the airport,” she recalls, “And I did not flag down a car that had a white person driving it. I needed a soul mate. And I knew that the only soul mates I could really trust at that moment , in that city, in the mood of that city, was to find a black man in a car, or a black woman, and to ask for a ride. And that was a very interesting moment because we flew to New York late at night and the next morning when I saw the first black person on the street I wanted to hug him. I had so much respect and love inside of me at that moment that I forgot that I was white. And maybe I never even thought of it before or after, but at that moment I needed to hug somebody who was black.”

Her son, now 64, also values having taken part in the Selma march, she says, adding “I think that if I could ever encourage people what to do when they become parents is expose your kids to experiences that they can feel enriches their lives. That they can then transmit. Because we become history. And when I talk today with Martin Luther King III, and I talk about our being there, it has given us such a bond. Because I was with his parents when he wasn’t there. And I was there with my son.”

I ASK EVA ABOUT HER PATH to becoming a leader, which reveals the importance she places on what she calls “the sense of the mass”, of people working together: “Leadership is a very interesting phenomenon. I don’t know if that is a conscious decision, ever. I think partly leadership has to do with seeing things that maybe somebody else doesn’t see at that moment. I never think of myself as a leader. A leader is somebody who is somewhat apart from others. So under my own terms, I’m not a leader. I’m a mentor.”

Eva was given a standing ovation when she accepted the Inaugural Excellence in Mentoring Award at the 2013 Forbes Women’s Summit. “If I ever have a tombstone–which I don’t really intend to have,” she says drolly, “I would want it to say she mentored well–because she was mentored well.”

As a mentor, she likes to get involved when ideas are nascent. “I love to get involved in projects that are not yet formed,” she says, “I love to incubate. I love to envision what an organization can be when it gets started or when it grows. And how can we together cooperate with other human beings to make things happen.”

|

One of the organizations is Women for Women International, which was founded to help women in war-torn regions. “Oh that must be–dear God–about twenty years ago when I met Zainab Salbi, who just came back from Pakistan,” she says. “And shortly before that she was on her honeymoon with Amjad Atallah, a marvelous Palestinian young man, in Kosovo, and realized the horrors of the war and wanted to do something for women.”

Women can sponsor “sisters” in affected areas, enabling them to take part in a year-long program in which they learn a trade and their legal rights, as well as hygiene, nutrition, and parenting. This has had a multiplying effect on the families and communities of the women who have taken part. The program, has trained 372,000 women between 1993 and 2012. “Zainab has done enormously,” Eva says, “And it’s one of those organizations that I was privileged to be there in the beginning.”

Another organization which Eva has been with since the beginning was founded by two opera singers, Monica Yunus and Camile Zamora, who wanted to make art more accessible. In its most high profile project, Sing for Hope (of which Eva is a trustee) brings 88 vividly decorated pianos to the streets and parks of New York City. On display for 2 weeks, the public artwork invites spontaneous performances and audiences from passerby. Additionally, Sing for Hope’s outreach program brings 1,500 professional artists to schools and healthcare facilities to teach in after school programs or perform concerts for hospital patients. In a promo clip, a staff member reports on how patients feel transported for a short while by the music, away from their suffering and surroundings. “For some, it may be the last concert they ever hear,” Eva says.

“When I first met these two young women,” she recalls, “and they were telling me about their ambitious goal to make this all happen, I said ‘Do you have a 501(c)3?'”

“You cannot do it yourselves alone,” she told the friends, “You have a career, you have a family, and if you want to have an organization, these are the things you have to have.” That, says Eva, was “a turning point. Because they realized yes, they do want to have an organization. And have 1500 volunteers going into schools. And in order to make it happen, they had to see that which I projected for them.”

“Now really and truly that’s not a big deal,” she adds.

“Transmitting information” is one of the aspects of mentoring, according to Eva, and applying for 501(c)3, or, non-profit status, is just one of many steps needed to create success. Eva deflects praise: the advice “just happened to be part of my life’s experience,” she says. I press Eva and ask if she isn’t being modest. Isn’t there more to mentoring than transmitting information?

“You know when one lives as long as I have, the circles of friendship, acquaintanceship and collaborators is almost mind-blowing. Very often I would say, ‘Hey, you know I would love to introduce you to that person or another person who would be so excited to work with you or to help you or to give you some ideas.’ So I think that is the greatest value I can provide others. And basically, you know, that’s not hard work. It is almost like, ‘how easy it is to be helpful.’ It really is.”

An organization in which she acted as a connector was Video Volunteers: “I got involved with it on an elevator, which is really the story of my life. I was going up in an elevator and there was a young woman [Jessica Mayberry] in the elevator. And it turned out we were both going to the same place, namely her parents’ home.”

Jessica’s mother had hoped Eva would convince her not to go to India to carry out her idea to train communities to produce videos that address issues relevant to their community. However, “The more I heard from the daughter and what she wanted to do,” says Eva, “the more I supported it.”

Jessica remembers the encounter well: “By the time we reached the floor we were going to she’d made me feel confident instead of anxious. By the time the party ended that evening, she’d gotten me a three-month documentary internship with her friend Kathy Eldon, and had convinced me to head to India.”

Eva also connected Jessica to fine-art photographer Lekha Singh, who recently produced the Netflix documentary The Square. Singh gave Video Volunteers its initial funding in the form of a $40,000 grant. “That was the make or break moment for me as a beginning social entrepreneur,” says Jessica, who had been torn between remaining in mainstream media or pursuing her idea of a grassroots Reuters in the most media-deprived parts of India.

The organization puts the power of filmmaking in the hands of community producers, who can take evidence to government administrators. The officials in turn have the evidence which gives them the leverage they need to act when citizens report on corruption or on the needs of the community.

Video Volunteers estimates their work has benefited over a million people since it was founded in 2003. “This wouldn’t have happened without Eva,” says Jessica.

WE SPEND THE REMAINING TIME talking about two organizations which bookend the last two decades: Free the Children, of which she has been the American board chair for 17 years, and her latest cause, The Exonerated, the board of which was formed just two days prior to this interview.

Free the Children began one morning when 12-year old Canadian boy Craig Kielberger was reading the paper. He was stunned to see the caption, “Battled child labour, boy, 12, murdered” next to a photo of a boy his own age, Iqbal Masih: From the ages of 4 to 10, Iqbal had lived as a bonded child laborer chained to a weaving loom in a carpet factory in Pakistan. He escaped and spoke out against child labour, gaining the attention of the media, for which he was assassinated. Craig tried to find out everything he could about child laborers. He and a group of 11 friends decided to fight child labor, later becoming Free the Children.

The principle of the organization is children helping children. Children in developed countries raise funds for the Adopt a Village Program, which builds schools and water wells in 8 developing countries, as well as addressing medical treatment, food security and alternative income. The organization estimates that, since 1995, it has provided 55,000 students with education every day, and a million people with improved access to clean water, healthcare and sanitation. It also boast an impressively figure of 10% for administrative costs, owing to partnerships with corporations who provide in-kind donations.

Eschewing handouts, it takes a holistic approach to investing in infrastructure. Where a traditional charity might donate a water pump, which may be too expensive to repair when broken, Free the Children ensures that communities are to repair water projects.

In 2002, Craig was nominated for a Nobel Peace prize, but lost to Jimmy Carter.

“My greatest joy is to help young people when they’re struggling with a good idea, with clearly something that could make a difference. I love to help them,” Eva says, “And we have about 1,000 schools, clinics, hospitals and villages that we have built with our grandchildren, who go every year with the local children in a number of countries in Africa and Asia. And it’s another one of those things it’s lovely to look at and to know that it happened.”

17 YEARS LATER, EVA IS NO LESS EXCITED for her most recent project, The Exonerated. I find out Sunny, who had earlier told me Eva was a great mentor, is one of its founders, along with her husband, Peter Pringle. “I met Sunny and Peter [Pringle] at a dinner party, and fell in love with them immediately,” Eva says.

What the couple had in common before they met was the horrific experience of being accused of a capital crime, unjustly convicted and sentenced to death row. When each of them were exonerated and released from jail, Sunny in the US, and Peter in Ireland, they joined the fight to end capital punishment. They met at an Amnesty International event and fell in love. Their dream is to create a residence in Ireland to help transition people who were wrongly accused of capital crimes and later found innocent.

“And you know, when I met Peter and Sunny,” says Eva, “that was a leap of faith. Of feeling that if I could be honored to meet 2 people who have sacrificed whatever life they have to help others the way they have, that was my leap of faith and their leap of faith with me to want to connect their lives to ours.”

AS WE WIND DOWN, I ask Eva how to get people who don’t care about social issues to care. She responds, “These are drops. None of us are creating an ocean. But we are dropping little drops of water. And it does create ripples. And I think that we have to be satisfied with the fact that each of us can only create the ripples. Actually we are lucky when we can.”

Eva leaves us with Sunny and Peter, and we film an impromptu interview with the couple. We find out they were married right there in Eva’s home. At one point, Sunny says it was worth having been wrongly accused and spent years in prison, so that she could meet Peter and they could have this life together helping others. They have such goodwill despite their incredibly harrowing experiences, it is difficult to remain unmoved.

The afternoon feels magical with this unexpected meeting. Eva sees us off, asking “Can we use the footage–it could be useful to them?” “Absolutely,” I say, glad we can be helpful in some way. When she looks at me, it is with the same penetrating look. Withholding judgment, looking deeply as if to see what is there. Almost invisibly, she’s played the role of connector again, connecting another life, another cause. In a flash I imagine how many lives she has touched.

And I think back to that story of the Nazi soldier she played off jokingly. I imagine that soldier–for, is the Nazi a Nazi in that moment when he lets the Jewish girl escape?–being given that piercing stare by a 14-year old Eva Haller; and I feel how completely convinced he must have been: that she was indeed far too young, and too beautiful, and how she must live.

Page created on 3/1/2016 4:39:02 PM

Last edited 3/6/2023 1:08:59 PM