|

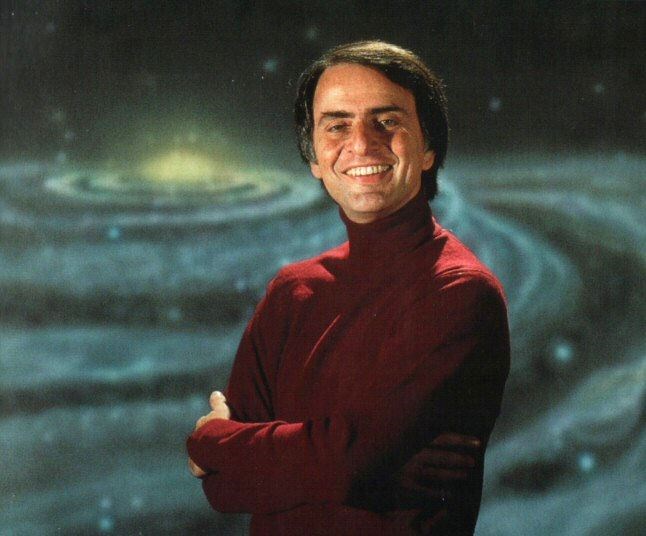

| Carl Sagan: Science Popularizer Extraordinaire (http://www.wwu.edu/depts/skywise/a101_seti.html) |

Carl Sagan came into the world as a small conglomeration of starstuff on November 9, 1934, and passed from this world on December 20, 1996. He was a brilliant scientist who made many discoveries, but is best remembered for his successful outreaches to the general public. Sagan contributed to the explanations of Venus' extremely high surface temperatures (caused by the "greenhouse effect"), Mars' seasonal climate changes (caused by wind-blown dust particles), and the red color of Titan (caused by complicated organic molecules).

Carl Sagan first became known as a research scientist. He had training in astronomy and biology, and brought a unique perspective to the fields of planetary science and exobiology. His most significant early work regarded the atmosphere of Venus. Discoveries made when he was still in school nullified the original model of Venus’ atmosphere, which suggested an Earthlike atmosphere, and instead suggested that it had a very hot surface. Sagan’s research built on this knowledge. He used the first computed greenhouse model for the atmosphere, which determined the surface temperature of Venus to be hundreds of degrees hotter than an airless planet. He would continue work on his models throughout the 1960s, determining what is now our basic knowledge of the atmosphere of Venus. Sagan also created a model of the Martian atmosphere, which was later confirmed, proposing that wind-blown dust produces quasi-seasonal changes on the surface.

Other than planetary science, another of Sagan’s interests was exobiology. Many astronomers considered these to lie outside of respectable science. As a result, he received more encouragement from biologists such as Stanley Miller and Joshua Lederberg early in his career.

Meanwhile, Sagan was gaining popularity as a teacher and public lecturer, winning teaching awards at Harvard and Cornell. In 1966, he published his book Intelligent Life in the Universe, achieving some national attention. He wrote an article published in National Geographic in 1967 on potential life in the universe, and made a few TV appearances. Students loved him, but some colleagues accused him of selling out, and he was denied tenure to Harvard in 1967. However, Cornell offered him an endowed chair which was perfect for him to continue his appearances in the media and his work as a popularizer of science.

One of Sagan’s main interests was to increase public knowledge on science and to expose pseudoscience. He organized two public symposia on fringe-science topics at the American Association of the Advancement of Science. The first symposium, in 1969, was about the existence of UFOs. J. Allen Hynek and James McDonald argued in favor of UFO studies; Sagan, Donald Menzel, and Lester Grinspoon argued against them. The second symposium, in 1974, regarded the theory of Immanuel Velikovsky that major catastrophes in Earth’s history were caused by planetary collisions. He directly addressed Sagan at this symposium, and by most accounts, Sagan was the hands-down winner against an indefensible theory. However, some people criticized him for not addressing all of Velikovsky’s points and making some careless calculations. Sagan lacked respect for Velikovsky, and thus made bitter enemies out of his supporters. Both symposia were covered extensively by the media.

In November 1973, he first appeared on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. He was articulate, informal, and enthusiastic, and would appear on the Tonight Show 26 times over the next 13 years. He appeared on a cover story on life in the universe in Time magazine in 1974, and a few weeks later published an article in TV Guide. In August 1976, he appeared on the cover of Newsweek, and in 1978 won a Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction for his book The Dragons of Eden. Sagan was a quickly rising star.

In the mid-late 1970s, Sagan formed a partnership with Gentry Lee to form Carl Sagan Enterprises and began working on a television series. Carl Sagan fell "rapturously in love" with the fellow scientist Ann Druyan, while working on the television show Cosmos with her. She became his third wife in 1981. Production of Cosmos began in 1977, and his commitment to the series quickly overshadowed his academic roles. Sagan would clash with many irritated colleagues at Cornell because of this. Cosmos aired in September of 1980, and Sagan quickly became a celebrity. The series won a Peabody Award, and over 400 million people around the world saw it. The accompanying book made the New York Times bestseller list for seventy weeks.

Time magazine put Sagan on their cover in October 1980. He moved back to Cornell after production of Cosmos, where he began receiving both compliments and death threats from strangers. Simon & Shuster offered an advance of $2 million for the yet unwritten book Contact to be made into a movie (Contact was published in 1985).

However, a growing concern of Sagan’s was Ronald Reagan’s policy towards nuclear arms. He decided to rally objections from the academic community against Reagan’s Space Defense Initiative and escalation of arms. At this time, former students Jim Pollack and Brian Toon with colleagues Rich Turco and Tom Ackerman were studying the effects of dust and atmospheric aerosols on climate, and realized that smoke has much greater impact than dust. As little as 100 burning cities could lead to nuclear winter. In 1982, they asked for Sagan’s aid in overcoming NASA’s objections to their work. This lead to the TTAPS paper published in late 1983 in Science magazine. TTAPS warned of the dangers of nuclear winter and global cooling. American pro-nuclear forces attacked the theory of nuclear winter as a fraud. Sagan debated well-known scientist Edward Teller on nuclear winter before a special convocation of Congress, and led a delegation to meet with Pope John Paul II, who issued a papal statement against build-up of nuclear arsenals. Many people credit Sagan’s support of nuclear winter theory as vital in the move towards nuclear disarmament.

When the Reagan administration drastically cut back on NASA funding, Sagan saw potential for international collaboration with the USSR under Mikhail Gorbachev. He formed a working relationship with Roald Sagdeev, the director of the Space Research Institute in Moscow. Together they opened up the Soviet planetary exploration program, which ran very well for a few years until the USSR spit up and many scientists went out of work.

In 1989, Sagan’s campaign for human expansion to Mars was failing. NASA struggled for the resources to maintain a program for robotic space exploration after a decade of budget cuts. However, Sagan was about to make his worst blunder. In autumn of 1990, Iraq threatened to set fire to the nations’ oil wells when threatened with military opposition to its invasion of Kuwait. Sagan feared that this would cause a small-scale nuclear winter, and went public with dire predictions. The oil wells were burned in January 1991, and there were no climatic effects. Sagan’s authority was undermined, and he was widely criticized. A second blow came in 1992, when he was nominated for membership in the National Academy of Sciences but was ultimately rejected. In 1993, the NASA SETI program to search for extraterrestrial life, which Sagan had long supported, was terminated by Congress. Things were going very poorly, and though he was awarded the Public Welfare Medal in 1994 by the National Academy of Sciences, he was no longer in the public eye.

In his final years, Sagan primarily fought against pseudoscience. His column in Parade, where he discussed science and debunked pseudoscience, was published regularly for over a decade. He published three books: Pale Blue Dot, The Demon-Haunted World, and Billions and Billions. With his death in 1996, we lost a great teacher and scientist.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Carl Sagan nació el 9 de noviembre de 1934, y murió el 20 de diciembre de 1996. Era un científico muy inteligente que descubrió mucho, pero es más conocido para su trabajo de ayudar al público entender las ciencias naturales. Ayudó a descubrir el secreto de las temperaturas muy altas en Venus (a causa del "efecto invernadero"), los cambiantes del clima de Marte (a causa del viento actuando en el polvo), y el color rojo de Titán (a causa de moléculas orgánicas y complicadas).

Carl Sagan fue conocido primero como un científico de investigación. Fue entrenado en astronomía y biología, y trae una perspectiva nueva a los sujetos de ciencias planetarias y exobiología. Su trabajo más famoso fue sobre la atmósfera de Venus. Cuando todavía estaba en la escuela, estudios en la ciencia descubrieron que el modelo viejo del clima de Venus fue falso. Venus no tenía un clima como la Tierra, como los científicos habían creído--tenía un clima muy caliente. Sagan usó el primer modelo del efecto invernadero para el clima de Venus, que determinó que la temperatura de la superficie de ese planeta era cientos de grados más caliente que las temperaturas de la Tierra. Durante los años 1960, la investigación de Sagan sobre Venus determinó lo que ahora es nuestro conocimiento básico de ese planeta. También creó un modelo de la atmósfera de Marte, que fue confirmado algunos años después, que propuso que el viento actuando en el polvo creaba los cambiantes como las temporadas en la superficie del planeta.

Además que ciencias planetarias, alguno de los intereses de Sagan era exobiología. Muchos astrónomos consideraban que sus investigaciones eran fuera de ciencias respetables. A causa de eso, recibía más aprobación de biólogos como Stanley Miller y Joshua Lederberg temprano en su carera.

A la vez, Sagan ganaba popularidad como un maestro y profesor público. Ganó premios de enseñanza a Harvard y Cornell. En 1966, publicó su libro Vida Inteligente en el Universo, y por eso recibió un poco de atención nacional. Escribió un artículo que fue publicado en National Geographic en 1967 sobre el potencial vida en el universo, y apareció en televisión algunas veces. Estudiantes le amaban, pero algunos compañeros de trabajo le acusaron de venderse, y Sagan no ganó la tenencia en Harvard en 1967. Pero Cornell le ofreció una cátedra a él, que fue perfecta para Sagan para continuar sus apariencias en los medios de comunicación y su trabajo como un divulgador de ciencias naturales.

Algunos de los intereses principales de Carl Sagan era aumentar el conocimiento del público de ciencias naturales y exponer pseudociencia. Organizó dos simposios públicos sobre temas de pseudociencia en la Asociación Americana de la Promoción de Ciencias Naturales. El primer simposio, en 1969, era sobre la existencia de OVNIs (UFOs). J. Allen Hynek y James McDonald apoyaban ciencias de UFOs; Sagan, Donald Menzel, y Lester Grinspoon atacaban esta posición. El segundo simposio, en 1974, fue sobre la teoría de Immanuel Velikovsky que grandes catástrofes en la historia de la Tierra fueron a causa de colisiones planetarias. Dirigió directamente Sagan en este simposio, y muchas personas piensan que Sagan fue el ganador obviamente en contra de una teoría indefensible. Pero algunas personas le criticaban para no dirigirse a todos los puntos de Velikovsky y hacer algunas calculaciones malas. Sagan no tuvo respeto para Velikovsky, y entonces personas a quienes les gustaba Velikovsky, no les gusto Sagan para nada. Los medios de comunicaciones seguían los dos simposios.

En Noviembre de 1973, apareció en el Tonight Show con Johnny Carson por primer vez. Era articulado, informal, y entusiasmado, y aparecería en este programa 26 veces en los próximos 13 años. Apareció en un cuento de portada sobre la vida en el universo en la revista Time en 1974, y algunas semanas después publicó un articulo en TV Guide. En agosto de 1976, apareció en la portada de Newsweek, y en 1978 ganó el Premio de Pulitzer en no ficción general por su libro Los Dragones de Edén. Sagan era una estrella ascendiendo rápidamente.

A fines de los años ‘70s, Sagan formó una asociación con Gentry Lee para formar Carl Sagan Enterprises y comenzó a hacer una serie de televisión. Sagan y Ann Druyan, una científica, se enamoran mucho cuando trabajaron en el programa de televisión Cosmos juntos. Se casaron en 1981; Druyan era la tercera esposa de Sagan. Empezaron a producir Cosmos en 1977, y pronto era obvio que le gustaba el programa mucho más que sus funciones académicas. Sagan tuvo muchos argumentos con compañeros de trabajo en Cornell sobre esto. Cuando Cosmos fue transmitido en septiembre de 1980, Sagan rápidamente se convirtió en una celebridad. La serie ganó un Premio de Peabody, y más de 400 millones de personas en todo el mundo la vieron. El libro que acompañó la serie estuvo en la lista de mejores libros del New York Times por 70 semanas.

Sagan estuvo en la portaba de Time otra vez en octubre de 1980. Regresó a Cornell después de la producción de Cosmos, donde comenzó a recibir complementos y amenazas de muerte. Simon & Shuster le ofrecieron a él un avance de dos millones de dólares para hacer el libro, aún no escrito, Contacten una película (Contact fue publicado en 1985).

Pero una preocupación creciente de Sagan era la política de las armas nucleares. Decidió trabajar para organizar objeciones de la comunidad académica contra la Iniciativa de Defensa del Espacio (Space Defense Initiative) de Reagan y el crecimiento de las armas. A la vez, ex estudiantes Jim Pollack y Brian Toon (con compañeros de trabajo Rich Turco y Tom Ackerman) comenzaron a estudiar los efectos de polvo y aerosoles de la atmósfera en el clima, y descubrieron que el humo tenía un impacto mucho más grande que el del polvo. Solo 100 ciudades en fuego podrían crear un invierno nuclear. En 1982, le preguntaron a Sagan por ayuda contra las objeciones de NASA de su trabajo. Entonces, el papel del TTAPS fue publicado a fines de 1983 en la revista Science. TTAPS advirtió de los peligros de invierno nuclear y el enfriamiento global. Fuerzas Pro-nucleares de America atacaron este papel como un fraude. Sagan luchó contra la oposición y apoyó la teoría del invierno nuclear; muchas personas piensan que el apoyo de Sagan fue vital en el movimiento hacia el desarme nuclear.

En sus años finales, Sagan primeramente lucho contra la pseudociencia. Con su muerte en 1996, perdimos un gran científico y profesor.

Page created on 3/4/2012 12:00:00 AM

Last edited 9/19/2024 8:27:41 PM

Morrison, David. "Carl Sagan's Life and Legacy as Scientist, Teacher, and Skeptic." [Online] Available http://www.csicop.org/. 2007.

Druyan - Sagan, Associates. "Carl Sagan." [Online] Available www.carlsagan.com. 2009.

Quarles, Norma. "Carl Sagan Dies at 62: Astronomer, Author Looked for What the Future Might Hold." [Online] Available http://www.cnn.com/US/9612/20/sagan/. 20 Dec. 1996.

Esta página de Web fue creada para un proyecto de una clase de español; una mitad es escrita en inglés, y la otra mitad en un intento de español mediocre. Esperamos que no sea muy ofensivo si no escribimos exactamente correcto.