US Senator John McCain passed away August 25, 2018 after fighting brain cancer. He was a pilot in the Navy, a Vietnam prisoner of war, a Republican presidential candidate, and served as a United States senator for 30 years.

Whether as a prisoner-of-war in a solitary confinement cell in Hanoi, or walking the halls of Congress, Senator John McCain displayed a sense of honor and justice that earned the respect of his colleagues on both sides of the aisle.

His service to his country during the Vietnam War stands out as one of the shining examples of heroism during that era. As a member of a prominent navy family, the seriously injured McCain was offered an early release when he was shot down in 1967. Sensing a publicity stunt by the North Vietnamese, McCain cited military protocol and insisted that POWs captured before him be released first. He was held in a prison camp for five and a half years.

McCain won a congressional seat after retiring from the military with a Bronze Star, a Silver Star, a Purple Heart, and a Distinguished Flying Cross for his bravery. A senator since 1986, he aggressively pursued campaign finance reform, anti-tobacco legislation, lower taxes, a cleaner environment, and more resources for public education--often crafting bipartisan solutions in bitterly partisan surroundings. He was known as a politician who would buck the party lines, such as his famous "thumbs-down" vote on repealing the Affordable Cart Act in 2018.

In a career of public service that spans almost fifty years, McCain defined himself by his strong leadership, patriotism, and unswerving allegiance to principle over partisanship.

When he ran for president, he defended his opponent Barack OBama against a voter who made disparaging comments, mistaking Obama for an Arab. McCain said elsewhere, "I want to fight, and I will fight,” he said. “But I will be respectful. I admire Sen. Obama and his accomplishments, and I will respect him.”

Obama was invited to speak at McCain's funeral and said this: "John McCain and I were members of different generations, came from completely different backgrounds, and competed at the highest level of politics. But we shared, for all our differences, a fidelity to something higher – the ideals for which generations of Americans and immigrants alike have fought, marched, and sacrificed. We saw our political battles, even, as a privilege, something noble, an opportunity to serve as stewards of those high ideals at home, and to advance them around the world. We saw this country as a place where anything is possible – and citizenship as our patriotic obligation to ensure it forever remains that way. Few of us have been tested the way John once was, or required to show the kind of courage that he did. But all of us can aspire to the courage to put the greater good above our own. At John’s best, he showed us what that means. And for that, we are all in his debt. Michelle and I send our most heartfelt condolences to Cindy and their family.”

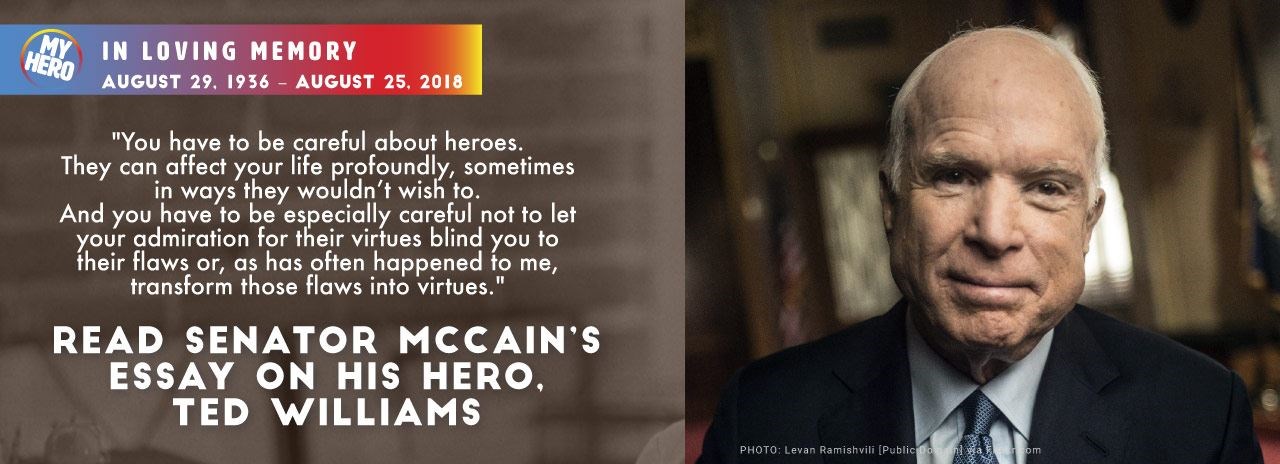

Senator John McCainLevan Ramishvili [Public Domain] via Flickr.comA friend of mine, Bob Craner, once told me a story of hero worship that was a cautionary tale. He was an ardent and rather obdurate fan of Ted Williams, the great Boston Red Sox slugger and the last man in baseball to hit .400. For a number of years, the hard-hitting St. Louis outfielder, Stan Musial, seven-time National League batting champion, had been considered one of Williams's closest rivals for the claim of best hitter in baseball. Bob, out of blind loyalty to his hero, had nothing but contempt for the popular Musial.

Senator John McCainLevan Ramishvili [Public Domain] via Flickr.comA friend of mine, Bob Craner, once told me a story of hero worship that was a cautionary tale. He was an ardent and rather obdurate fan of Ted Williams, the great Boston Red Sox slugger and the last man in baseball to hit .400. For a number of years, the hard-hitting St. Louis outfielder, Stan Musial, seven-time National League batting champion, had been considered one of Williams's closest rivals for the claim of best hitter in baseball. Bob, out of blind loyalty to his hero, had nothing but contempt for the popular Musial.

In high school, Bob had had a crush on a girl he wanted to ask out but who he feared might reject him. After several weeks of silently pining away for the object of his affection, he finally screwed up his courage enough to risk rejection. To his great relief she agreed to go to dinner with him, and Bob spent the next few days in excited anticipation of his dream date. When the happy occasion arrived, the two got along quite well, and my friend wondered why he had waited so long to approach her. At some point during their conversation, they declared their mutual love of baseball, which only enhanced the young lady’s charms in the eyes of my love-struck friend, until, that is, she dropped her bombshell.

"I think Stan Musial is the greatest hitter in the game," she said. Bob ended the story there.

"What did you say to her," I asked.

"Nothing," he responded.

"Nothing?"

"Nothing. I never spoke to her again."

You have to be careful about heroes. They can affect your life profoundly, sometimes in way they wouldn’t wish to. And you have to be especially careful not to let your admiration for their virtues blind you to their flaws or, as has often happened to me, transform those flaws into virtues.

Ted Williams was my hero, too. There was much to admire about him, but as Ted himself would acknowledge, there were some aspects of his personality that weren’t usually considered virtues.

I was a boy when I first saw him at the plate. Allowing that my memory might have embellished the experience to suit my admiration for Ted, I recall that he hit two doubles and a home run that day. But it was a strikeout that I remember most vividly.

It was an away game. The Red Sox were playing the Senators at Griffith Stadium in Washington. When Ted swung at and missed a third strike, the Washington fans filled the ballpark with boos and catcalls. Ted turned toward the crowd and the boxes where the sportswriters who often gave him a hard time were enjoying the spectacle. Then he raised his head, stared defiantly at his tormentors, and spit in their general direction.

I loved him. He was in my estimation the greatest hitter in baseball, the greatest of all time for that matter. But the accomplishments of his legendary career were far from the only thing that attracted my admiration. He was a Marine aviator and decorated veteran of two wars. He was an exceptionally good pilot. He was playing his fourth season in the major leagues when he was called up for World War II. The year before he had hit .406. On opening day in 1942, he hit a home run his first at-bat. At the end of the season he reported for duty, after he had won his first triple crown for the best batting average, most runs batted in, and the most home runs. No telling what he might have done during the three seasons he missed while on active duty. He didn’t get a hit his first at-bat after returning from the war. He hit a home run on his second trip to the plate.

In Korea, he had flown in the same squadron as John Glenn, who called him the best natural pilot he had ever seen. He hadn't wanted to go when they called him back to active duty in 1952. He was thirty-three years old, and had a wife and daughter to support. He had also shattered his left elbow during the All-Star game that year when he ran into the fence chasing a fly ball. But he went to Korea and did his duty. Most people assumed he would never play professional baseball again. On one combat mission, enemy antiaircraft fire hit his plane, and disabled its hydraulics. With his plane on fire he couldn’t get his landing gear down. Ground control radioed him to eject. He should have, but instead he managed a wheels-up landing with his plane engulfed in flames, an act that took extraordinary skill and courage.

He was six feet four. He knew if he ejected his long legs would hit the instrument panel, breaking his knees. "I would rather have died," he said, "than never to have played baseball again."

I admired his courage and patriotism. I admired his astonishing accomplishments as a ball player. There is something in my character that is attracted to people with a strong independent streak in their personality. I liked rebels, particularly when I was young. And that is what I really liked about Ted Williams.

Later in life, I learned to keep that quality in perspective. Being defiant sorts, persons who go their own way are fine as long as they serve some greater purpose than their own vanity. Oftentimes, my own rebelliousness was simply self-indulgence. And I can't say I'm proud of that today.

I don't know what made Ted Williams so defiant, so adamantly his own man. He had had a tough childhood. He had a bad temper. And, by his own admission, he had "always been a problem guy." I'm not sure his individualism was always connected to some higher purpose than his own satisfaction. I don't think Ted thought it was. But when I was young, I thought him to be the toughest, feistiest, most independent man I had ever seen, and I loved him for it.

He had a bad year in 1954, suffered several injuries, and decided to retire at the end of the season. He was thirty-six years old, and well past his prime. He changed his mind and rejoined the Red Sox the following spring, but injuries plagued him for the next two seasons. Then in 1957, clearly aging, still battling with fans and sportswriters, still making trouble for himself, he hit .388 for the season, the best record since he had broken .400 in 1941. He won the league batting title that year. He won it the next year, too, when he was forty and hit .328. In 1959, he threw his bat in anger at striking out. It hit a lady in the stands, and Ted was ashamed of himself. The crowd’s boos were deafening. Then he hit a double his next at-bat.

For all his well-publicized temper and feuds, he was a kindhearted man. He worked tirelessly and without publicity to raise money for a children's cancer research clinic. Whenever a child with cancer wanted to see him, he came, alone.

In 1960, well into his forties, he decided to give up baseball. Age and injuries had slowed him, and the pressure he felt all his career to be the best was too much to handle anymore. He was as controversial as ever. When he stepped to the plate for the last at-bat of his career, the fans who often got mad at him, but who loved him, and who--he would later admit--he loved, stood on their feet to pay respect for the Splendid Splinter. He hit a home run. The crowd roared for him to come out of the dugout after he had run the bases. They wanted to acknowledge him, and they wanted him to acknowledge their love for him. They wanted him to tip his hat. He wouldn’t do it.

He left Fenway Park that afternoon, glad he had played ball and glad to be done with it. He loved the game, but he had played it the hard way, the lonely way, his own way. He had served his country with courage. He had given the game his best. The man who wouldn't tip his hat had been the greatest hitter who ever lived.

Page created on 9/1/2006 12:00:00 AM

Last edited 8/31/2018 12:35:07 AM

Copyright 2005 by The MY HERO Project

MY HERO thanks John McCain for contributing this essay to My Hero: Extraordinary People on the Heroes Who Inspire Them.

Thanks to Free Press for reprint rights of the above material.