REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION FROM THE CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR

In South Sudan, young people have grown up in the shadow of war and ethnic conflict. Now, they are using music to push back against the idea that those differences define them.

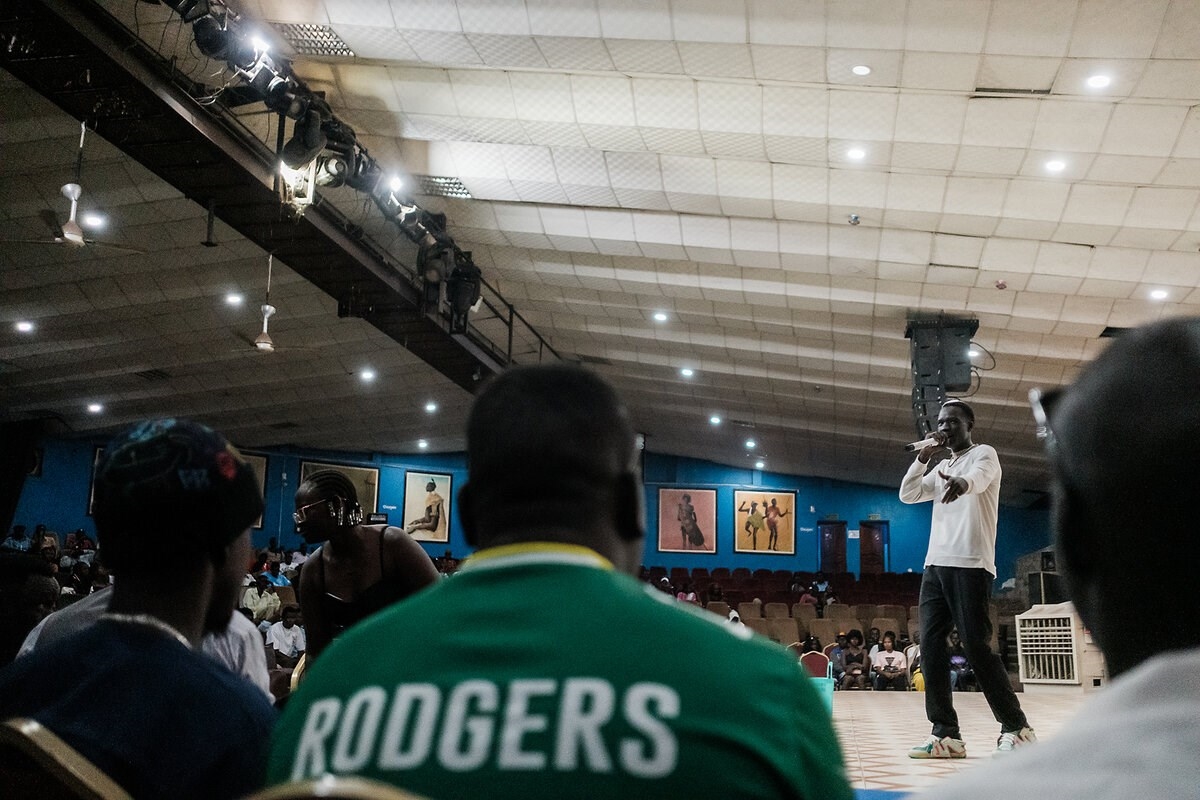

Audience members react to a performance during a weekly entertainment show at Nyakuron Cultural Centre in Juba, South Sudan, Aug. 21, 2025. Guy Peterson

Audience members react to a performance during a weekly entertainment show at Nyakuron Cultural Centre in Juba, South Sudan, Aug. 21, 2025. Guy Peterson

| Juba, South Sudan

Backstage at the Nyakuron Cultural Centre on a recent Thursday evening, Wigo Young Soon nervously awaits his turn to perform. Heavy rain drums on the roof as he whispers a mantra. “I believe in myself,” he says, preparing for the debut of his new hip-hop track, “Juba to London.”

In front of him is an audience of young South Sudanese. They munch on popcorn, chat, flirt, and lift their phones to capture the latest talent. For them, performers like Mr. Soon are a much-needed source of joy in turbulent times.

Independent since 2011, South Sudan has been riven by violence for most of its brief history. A civil war fueled by ethnic tensions gripped the country from 2013 to 2018, and in recent months, clashes between the president and his deputy have threatened to spill into another war.

The hundreds of young people who cheer for Mr. Soon from Nyakuron’s red velour seats have grown up in the shadow of conflict. But it is the last thing you’ll find in their music.

“When we are inside this hall, we are all the 64 tribes [in South Sudan],” says Isaac Anthony Lumori, better known here as MC Lumoex, the producer and musician who has been hosting this event, the Kilkilu Ana Entertainment Show, weekly since 2014.

For more than five decades, South Sudan was part of Africa’s largest country, Sudan, a vast collection of different ethnic groups and geographies sutured together by British colonialism. After a long civil war with the northern part of the country, South Sudan became independent in 2011.

Guy PetersonHip-hop musician Wigo Young Soon performs during a weekly entertainment show at the Nyakuron Cultural Centre in Juba, South Sudan, Aug. 21, 2025.

Guy PetersonHip-hop musician Wigo Young Soon performs during a weekly entertainment show at the Nyakuron Cultural Centre in Juba, South Sudan, Aug. 21, 2025.

But as the fight for independence receded into the past, old divisions between the country’s two largest ethnic groups – the Dinka and the Nuer – surged to the fore. In 2013, President Salva Kiir, a Dinka, abruptly dismissed his deputy Riek Machar, a Nuer, sparking a civil war.

“Once the external enemy [Sudan] was removed, they turned on each other,” explains Daniel Akech, a senior analyst for South Sudan with the International Crisis Group.

By the time the war ended in 2018 with a fragile power-sharing agreement between Mr. Kiir and Mr. Machar, it had claimed around 400,000 lives.

Mr. Soon’s grandmother was among them. When he was 7 years old, he watched a stray bullet fly through the window of his family home and strike her in the head.

He says this type of violence was so normalized that although he was distraught, “I couldn’t even cry.”

The open-mic nights at Nyakuron also had their origins in the conflict.

“We thought: How can we bring back smiles?” he recalls, sharply dressed in a grey waistcoat. “The war compelled us to open.”

Ever since, the evenings have been a pivotal space for artistic expression for young people in Juba. They have launched the career of South Sudan’s first-ever comedians, as well as dozens of musicians.

Young people here say that at Nyakuron – which also contains a studio, restaurants, and a soccer pitch – ethnic divisions are left at the door. And many openly resist the idea that ethnicity is the root cause of conflict here at all.

“South Sudan is a good country, but leaders want to spoil it,” Mr. Soon says. “That’s why you see people suffering.”

Mr. Akech agrees, arguing that politicians “are exploiting this [ethnic] structure of the country to advance their own interests.”

This March, conflict flared again after a Nuer youth militia overran a government military base in Nasir, in the country’s northeast, prompting a major security response. Mr. Machar – back in his role as Mr. Kiir’s vice president – was accused of links to the group, placed under house arrest, and charged with treason.

Since then, sporadic clashes have killed 2,000 civilians and displaced more than 300,000 people. In October, Barney Afako, a member of the U.N. Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan, warned the U.N. General Assembly that “all indicators point to a slide back toward another deadly war.”

For Sandra Abalo, Nyakuron is a refuge from the political clashes outside.

“Here, we don’t talk politics,” says the journalism student in her mid-20s. Dancing near the stage on the evening of Mr. Soon’s performance, she let the Afrobeats that buzzed through the blasting speakers take over her body, wiggling her hips.

Still, she couldn’t completely forget everything else.

“Life in South Sudan is very difficult because things these days [have] become very expensive,” she explains. Some 92% of the South Sudanese population lives below the poverty line – a 12% increase from the previous year, according to the African Development Bank. Cuts to aid, which makes up about 25% of the country’s GDP, have made the situation worse.

Like many others, Ms. Abalo’s father – who worked at the World Food Programme – lost his job in those cuts.

“My message to Donald Trump? ... Forgive South Sudan,” she says, laughing.

Guy PetersonRapper and producer Linus de Genius works on the "64 in 1" project with singer Hani Breva in his studio in Juba, South Sudan, Aug. 22, 2025.

Guy PetersonRapper and producer Linus de Genius works on the "64 in 1" project with singer Hani Breva in his studio in Juba, South Sudan, Aug. 22, 2025.Decorated rapper and producer Linus Junior Ochwo, known by the stage name “Linus de Genius,” is a regular performer at Nyakuron and has produced many of the artists who have passed through its doors.

Now, the musician from Uganda is working on what he hopes will be an antidote to the country’s violence and division. His project “64 in 1,” is a celebration of South Sudan – with one original song for each of the country’s tribes.

“Music has a greater power than anything ... it’s a simple way to gather people,” he says, running his fingers over the keys of his electric keyboard in his central Juba studio. “I want to contribute towards peace ... in a different way.”

Mr. Ochwo collaborates with local musicians, learning their languages and taking samples of traditional instruments. Then he produces tracks that blend those elements with modern beats. He has released at least two dozen so far.

“There is that richness in culture that I wanted to bring out, so that people understand that South Sudan has wealth,” he says.

Mr. Ochwo says his process has revealed how little many of South Sudan’s communities know about each other.

But if the project has in some way underscored what separates people here, it has also been a reminder of what unites them. Most of the songs are focused on themes like beauty and love.

“It’s like one umbrella [for] all these tribes,” Mr. Ochwo says. “If you play a song on a radio station for three minutes ... the people will come.”

Back at Nyakuron on the night of Mr. Soon’s performance, the crowd is on their feet beneath the bright fluorescent lights. For a moment, the bass lines seem to drown out the anxieties and differences that so many young people here are experiencing.

On this evening, they simply want to dance.

Page created on 1/12/2026 4:38:41 PM

Last edited 1/12/2026 4:52:40 PM