|

| Marie Curie Photo courtesy of Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-91224 |

Born Marya Sklowdowska in 1867 into a family of impoverished educators, the woman whom the world would know as Marie Curie grew up in Warsaw at a time when Poland was dominated by Tsarist Russia and school instruction in the native language was outlawed. Determined and defiant, Marie excelled at her studies (both the “official” courses conducted in Russian and the secret classes in Polish) and, after working eight years as a governess, was able to follow her older sister Bronya to Paris to study at the Sorbonne, where she ranked first in science and second in mathematics in a class of 2000 students.

|

| Pierre and Marie Curie 1906 Photo courtesy of Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-73356 |

Despite her academic success, scientific careers were almost entirely closed to women. Thanks to the intervention of one of her professors, Marie found work studying the magnetic properties of various steels. To perform this work, she needed instruction in a device—the quadrant electrometer—that had been perfected by a young physicist named Pierre Curie. As their attachment grew, their love deepened, culminating in their marriage in 1895. Two years later, Marie gave birth to their first child, Irene.

Marie then began work on her doctoral thesis, in which she explored the newly discovered science of radioactivity (a word she coined), measuring the energy released by different radioactive substances. Until then scientists thought of the atom as a solid ball, with nothing inside that could escape. Marie’s astounding discovery, that radioactivity was an atomic property, allowed scientists to explore the atom and threw open the door to twentieth-century science. Continuing her research, Marie, assisted by Pierre, isolated two new elements: polonium and radium. For their investigations into the workings of radioactive substances, Pierre and Marie were awarded the 1903 Nobel Prize in physics.

|

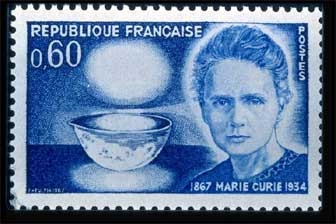

| IV-28 1967 France stamp was issued to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the birth of Marie Curie. It features a portrait of Dr. Curie and a bowl glowing with radium. Photo from www.xray.hmc.psu.edu/ rci/ |

As radium became known as a miracle substance, the Curies’ fame spread far and wide. In 1904, Marie gave birth to another daughter, Eve. But two years later, Pierre, his body wracked by exposure to radiation, slipped before the wheels of a horse-drawn cart and was killed. Marie assumed Pierre’s professorship at the Sorbonne and threw herself even more ardently into her research. In 1911, she was awarded a second Nobel Prize, in chemistry, for her discovery of polonium and radium. But her glorious moment was clouded by scandal. Her affair with a married colleague, the physicist Paul Langevin, had been made public, and she was assailed in the press as an immoral, foreign woman.

|

| Chemistry Lab Photo courtesy of RF5468856| RF| © Royalty-Free/Corbis |

Her reputation recovered during World War I, when she commandeered the automobiles of rich French women and organized a fleet of mobile X-ray units (which became known as “Les Petites Curies”) to assist front-line doctors, who until then had been mutilating soldiers by probing and amputating limbs. In the early 1920s, she came to the United States on a tour to raise money for research; the resultant publicity helped create the myth of Madame Curie, the self-sacrificing scientist who found radium and provided a panacea for man’s ills, especially cancer. She helped guide her daughter Irene’s budding scientific career, thus establishing a Curie dynasty in radioactive science that continues to this day. Irene, with her husband, Frederic Joliot, would themselves win the Nobel Prize in 1935 for creating artificial radioactivity, but Marie would not live to see the results of their accomplishment. Succumbing to the long-term effects of radiation exposure, she died in the summer of 1934.

Page created on 2/17/2006 11:36:39 AM

Last edited 2/13/2020 3:01:43 AM