Selma BurkeWikipedia

Selma BurkeWikipedia

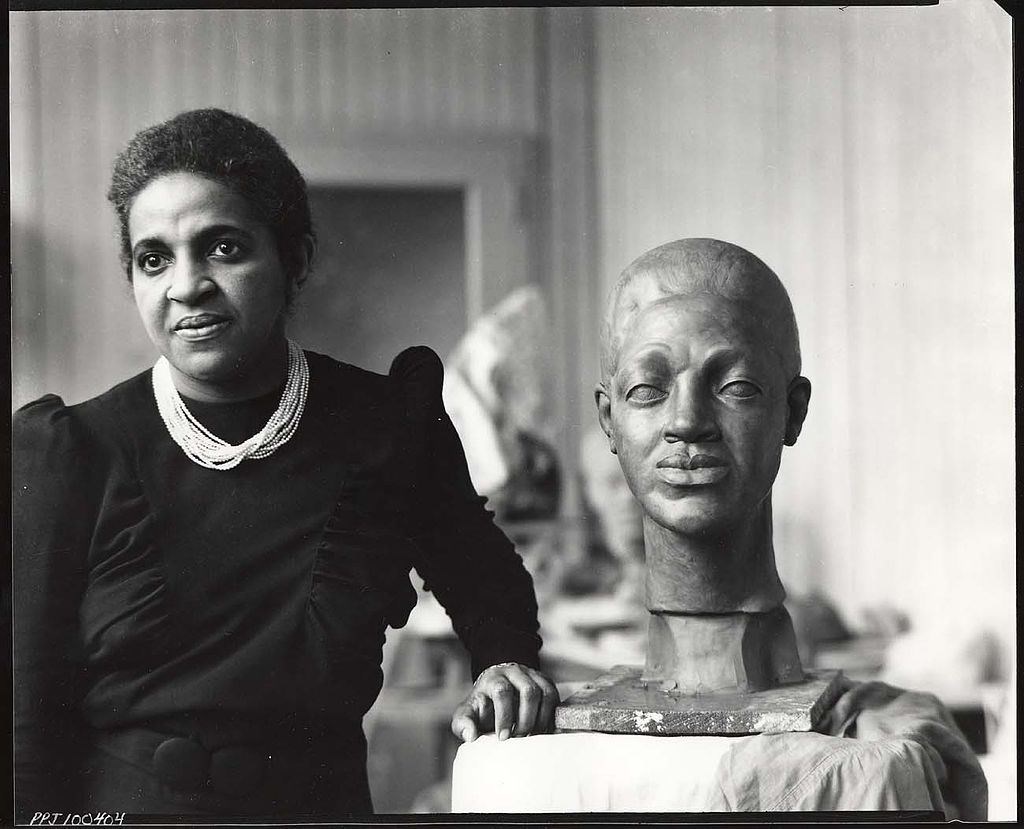

The Harlem Renaissance was a pivotal moment in the history of the United States. Between 1918 and the mid-1930s was a time of prosperity for African Americans in the wake of the Civil War. Harlem became a mecca for artists everywhere and was one of the big cities that displayed the power of the roaring twenties. Black artists during this time rejected the stereotypes that had been imposed on them, like blackface and the stripping of sexuality, and showed the world their artistic capabilities. The movement is also known as the “New Negro Movement,” centered in the heart of Harlem, but the movement also inspired African Americans who lived in Europe. Out of this exciting period came Selma Burke, a sculptor from North Carolina.

Burke’s work focused heavily on human emotion and experience. She sculpted many famous African Americans, such as Duke Wellington. She received honorary doctorates from several schools. Her influence was so widespread that the governor of Pennsylvania declared July 29th, 1975, Selma Burke Day.

Selma Burke was born in Mooresville, North Carolina, in 1900. She was the seventh child of a local reverend. Burke attended school in the South at a time when segregation was law. Her school was one room and was shared by all grades. Burke’s interest in art was initiated by her daily walk to the nearby river. She would stick her hand in the mud and let it intertwine with her hands. Burke said about the riverbed, “It was there in 1907 that I discovered me." She was seven when she discovered her interest in sculpting; she was especially intrigued by African American ritual sculpture pieces. Her family was very supportive of her artistic pursuit. Burke attended Winston Salem State University, and after graduating, she went to nursing school in Raleigh, South Carolina. Selma married childhood friend Durant Woodward in 1928, and her marriage ended a year later with his tragic death.

Selma moved to New York in 1935, during the dazzling Harlem Renaissance. She had moved to the city with the intention of practicing as a private nurse. Selma’s career as a nurse allowed her to live somewhat of an average life during the Great Depression. She lived in Hell’s Kitchen during this time and dated a writer, Claude McKay. The relationship was toxic and intense; Claude would often destroy Selma’s clay models when he didn’t think it was up to his artistic standards. During this time Burke had begun to teach at Harlem Community Arts Center. Along with making the acquaintance of a sculptor named Augusta Savage, this endeavor allowed Selma the opportunity of the New Deal Federal Project. In the 1930s, Burke traveled twice to Europe, once on a fellowship in Vienna and the other time on a brief stint to Paris. In Paris, Selma got the chance to meet Henri Matisse and study with Aristide Maillol, who both praised her work; Burke was able to complete one of her most recognized works, Frau Keller.

In 1940, Burke moved back to New York and founded the Selma Burke School of Sculpture. She also got her MFA from Columbia University in 1941. Throughout her life, Selma Burke was a beacon for African American progression and was a massive advocate of black artistry. She saw art as a way out of racial prejudices and a medium that could ultimately change the world for the better. In Mooreville, black children were banned from using the public library. Burke raised money to help get the ban lifted. Burke’s last major work was a piece honoring Martin Luther King in Charlotte. Selma Burke died on August 29th, 1995 in New Hope, Pennsylvania.

Burke is widely known for her portrait of Franklin D. Roosevelt. She won a stringent competition and was subsequently commissioned to do the portrait. Burke requested a live sit-in with the president. The president agreed, and three meetings were scheduled; unfortunately, Roosevelt passed. Initially, Mrs. Roosevelt was against the youthful approach Burke had taken in portraying FDR. Burke famously said soon after, “This profile is not for today, but for tomorrow and all-time.” Her work is widely known to have influenced the picture seen on the dime today. The work was sadly not credited to her but to the chief engraver, John Sinnock, a decision that Selma fought against her whole life. Selma was a true artist for the people, but she had a special emphasis on the generation after her. She wanted to guarantee unequivocal access to the younger artists who would follow in her footsteps.

Page created on 9/1/2020 6:19:35 AM

Last edited 4/27/2021 11:17:45 PM

, . . [Online] Available https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/burke-selma-hortense-1900-1995/.

, . https://americanart.si.edu/artist/selma-burke-27983. [Online] Available https://americanart.si.edu/artist/selma-burke-27983.

, . . [Online] Available https://www.ncpedia.org/burke-selma-hortense.

, . . [Online] Available https://thejohnsoncollection.org/selma-burke/.