Storytelling wasn’t something that I ever thought of as a source of power, per se, but it's tremendously powerful.

Margot Lee ShetterlyBill Ingalls / Public domain

Margot Lee ShetterlyBill Ingalls / Public domain

Katherine Johnson, who recently passed away at age 101, has become a household name thanks to writer and researcher Margot Lee Shetterly. Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, and Mary Jackson were African American mathematicians, at that time called “human computers,” who worked for NASA during the space race. Though their contributions were significant, their efforts were largely unrecognized before the publication of Shetterly’s groundbreaking 2016 biography, “Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race.”

Margot Lee Shetterly grew up in a unique community in Hampton, Virginia, that naturally led to her interest in celebrating these unsung heroes. Shetterly’s father worked for NASA as a research scientist, and her mother was an English professor at a historically black university. Shetterly counts her parents as her most important heroes. In an interview with MY HERO, she said, “They are both very, very dedicated to each of their careers … and yet they were also extremely committed to our family and to our community. I feel like I could not have been luckier in terms of the start that I had in life with my parents.” Shetterly channeled the dedication she saw in her parents into her own professional passion—and one that melded her parents’ careers into a venture perfectly suited for her.

During her childhood, Shetterly was surrounded by heroes not just in her immediate family, but also in her community as a whole. She lived side by side with many African Americans who worked at NASA, and she thus had daily examples of people of color working in math and science fields. While the Johnson et al. may seem extraordinary to those outside Hampton, for Shetterly, this hard-working heritage felt completely normal: “[The community was] so committed to making sure that my generation and future generations got a good education, got the best start in life, encouraged us to do our best in every way … I got to grow up with that as sort of the norm, and of course that’s not the norm for everyone. The importance of having that early in life cannot be overstated.”

NASA Human Computers (Mary Jackson on far right)NASA / Public domain

NASA Human Computers (Mary Jackson on far right)NASA / Public domain

Johnson, Vaughan and Jackson exemplified this industrious spirit, and overcame enormous obstacles in the process. Katherine Johnson calculated trajectories and orbits for astronauts, the first African American woman to do so. In her interview, Shetterly points out that despite popular opinion, Johnson was not exceptional. She was not a lone black mathematician among an otherwise non-math-oriented black community. Rather, her exception was that she was able to break into a white- and male-dominated field through her tenacity.

Shetterly said, “I think this thing of ‘if you’re black and if you achieve you’re exceptional,’ or ‘if you’re a woman and you’re good at math, you’re exceptional,’ is really damaging because it challenges you to be one or the other, when you can be both black and good at math and have no internal contradictions.” Katherine Johnson seems to have rejected this contradiction, and she therefore demanded the equality that she knew she deserved. This self-assuredness helped her become a critical mathematician for astronaut John Glenn. In fact, before beginning his Friendship 7 orbital mission, he asked for Johnson specifically before takeoff, wary of trusting the electronic computations without Johnson confirming them manually.

As for Dorothy Vaughan, she supervised a segregated section of NASA called West Area Computers, to which Katherine Johnson was originally assigned. Vaughan, Johnson, and the other black “girls” had to use separate bathrooms and dining facilities, in addition to their separate work space. Vaughan was a trailblazer in her own right, as the first African American supervisor for NASA, and later its first African American manager, all before NASA desegregated in 1958.

Mary Jackson was also one of Dorothy Vaughan’s “computers” and later worked for an engineer in a pressure tunnel measuring 4 by 4 feet. The engineer, Kazimierz Czarnecki, encouraged her to become an engineer herself, so she valiantly fought to desegregate the after-school math and physics program given by the University of Virginia at then-segregated Hampton High School. Jackson went on to become NASA’s first African American engineer.

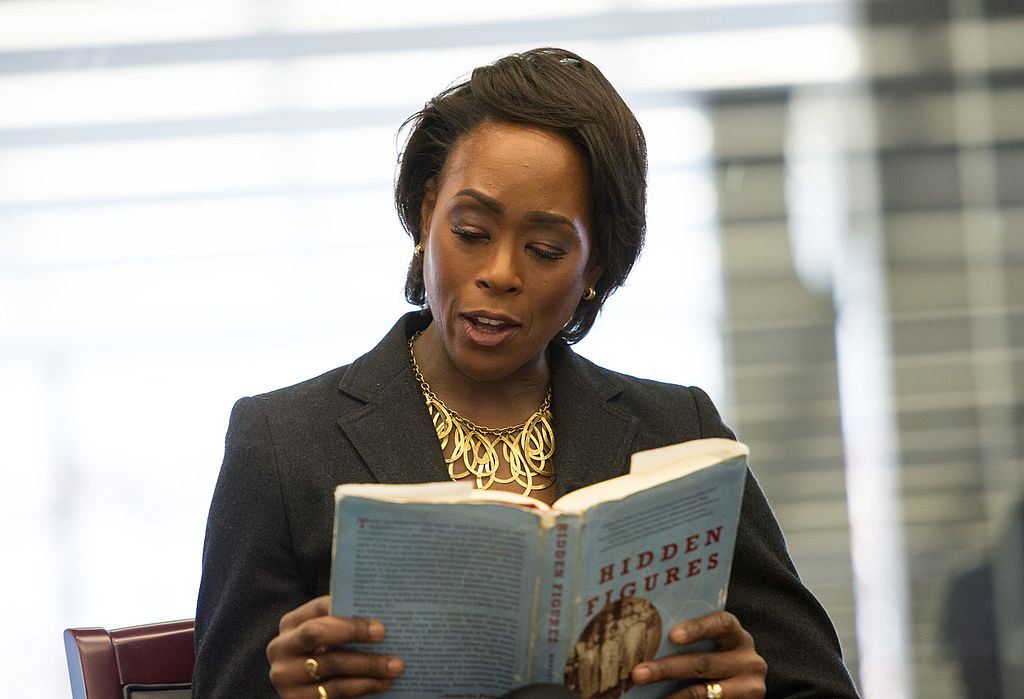

Margot Lee Shetterly reading from Hidden Figures at Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library in Washington, D.C.NASA/Aubrey Gemignani / Public domainIn regards to her previous work at a community school science club, Jackson is quoted as saying, "Sometimes they are not aware of the number of black scientists, and don't even know of the career opportunities until it is too late." In our interview with Shetterly, she expressed the same sentiment, especially regarding the stereotype of a scientist as a white man with crazy hair and glasses like Einstein: “I think the reason why these women and their stories are so important is because it shines a light on these people who have been doing the work, and it says to young women, and particularly young women of color, and really everyone, ‘This is what a scientist looks like as well. This is what a mathematician looks like as well. These are people who excel in these fields as well.’ When everyone has a broader idea of what a scientist or mathematician looks like, then it becomes second-nature for us to look everywhere for us to find that talent.”

Margot Lee Shetterly reading from Hidden Figures at Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library in Washington, D.C.NASA/Aubrey Gemignani / Public domainIn regards to her previous work at a community school science club, Jackson is quoted as saying, "Sometimes they are not aware of the number of black scientists, and don't even know of the career opportunities until it is too late." In our interview with Shetterly, she expressed the same sentiment, especially regarding the stereotype of a scientist as a white man with crazy hair and glasses like Einstein: “I think the reason why these women and their stories are so important is because it shines a light on these people who have been doing the work, and it says to young women, and particularly young women of color, and really everyone, ‘This is what a scientist looks like as well. This is what a mathematician looks like as well. These are people who excel in these fields as well.’ When everyone has a broader idea of what a scientist or mathematician looks like, then it becomes second-nature for us to look everywhere for us to find that talent.”

After college, Margot Lee Shetterly worked in investment banking for such power houses as J.P. Morgan and Merrill Lynch. Over time, however, she switched her focus to media and storytelling. “Storytelling wasn’t something that I ever thought of as a source of power, per se, but it’s tremendously powerful … We get to live in their [the storytellers'] lives and we get to hopefully develop a sense of empathy and close the gap between the idea that we have between ‘us’ and ‘them.’ I think that is really the power of storytelling.” Shetterly certainly works to close this gap by showing Americans—and those around the world—that black Americans inhabit more spaces than is usually portrayed through our traditional media. And she continues on this journey through The Human Computer Project, which she founded in 2013 with the goal of, according to the project website, find and telling “the stories of the pioneering women who worked as mathematicians and ‘computers’ at the NACA and NASA in the early days of aeronautics and the American space program.”

At the close of her interview with MY HERO, Shetterly summarizes the roles of her hidden figures perfectly: “Katherine Johnson and these women … they really were both absolutely normal, wonderful people, and at the same time, real superheroes.” And that’s a perfect description of Shetterly as well.

Page created on 2/28/2020 11:01:35 PM

Last edited 4/13/2021 6:27:21 AM

Shannon Luders-Manuel is a two-time essayist for The New York Times, and the General Editor & Story Director for The MY HERO Project.